Deana: [00:00:00] Welcome to Stories for Power. I’m Deana Lewis and I’m a member of Just Practice Collaborative. Stories For Power is an oral history project produced by Just Practice Collaborative and Creative Interventions. It explores the political lineage and historical experiments that gave way to this wave of transformative justice, community accountability, and prison abolition.

In each episode of Stories for Power, we speak with activists and organizers from different cities who were, and continue to be, at the forefront of feminist abolitionist praxis. They talked about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the early 2000s through 2010, and how their work informed abolitionist, transformative justice, and community accountability organizing today.

Don’t [00:01:00] worry. If any terms or words have you confused, we will do our best to link to resources in the show notes, and you can always go back to listen to the special introduction episode for more context.

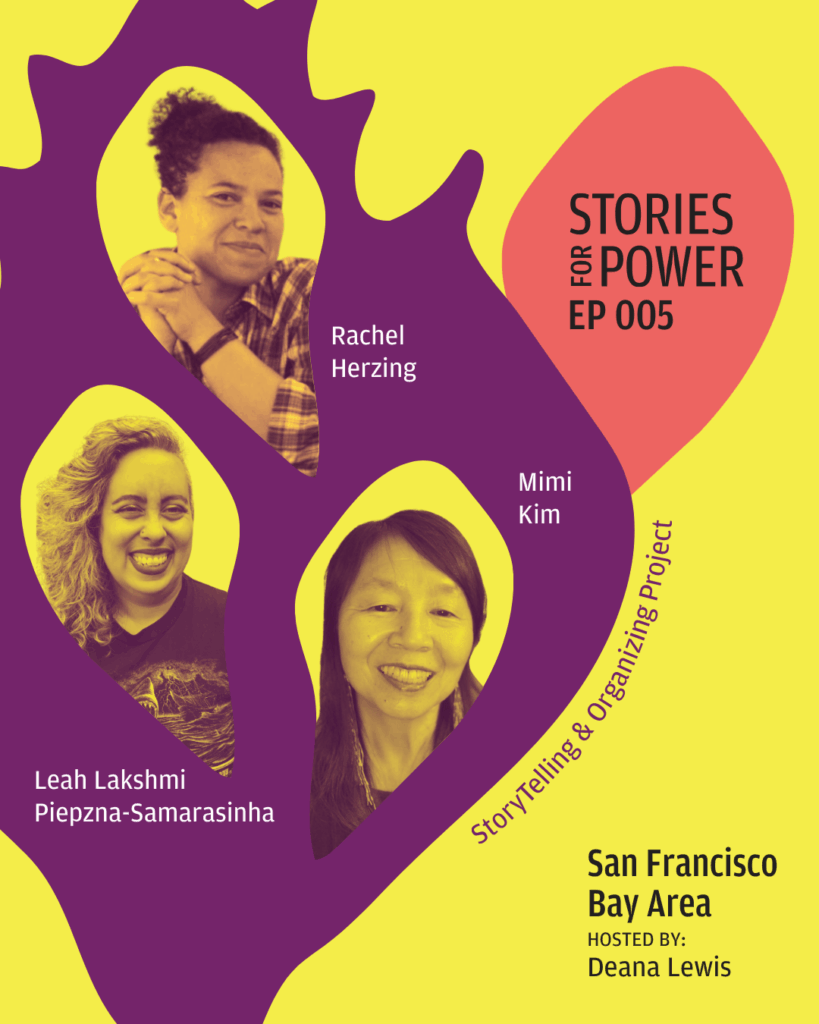

In this episode, you will hear from three inspiring abolitionist feminists, Rachel Herzing, Mimi Kim, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha. They talked about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the San Francisco Bay Area between the early 2000s and 2010, and how their work informed abolitionist, transformative justice, and community accountability organizing today.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We want to hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative want to share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence. Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

A note for our listeners, [00:02:00] we will be discussing violence, including police violence, intimate partner violence, and community violence. We encourage you to take care of yourself, and we understand that taking care of yourself can also look like not listening to this podcast until you’re ready.

Now, let me introduce our guests. They have amazing and extensive experiences and knowledge. I’ll do my best to summarize. We have linked their full bios in the show notes. You can also learn more on our website: storiesforpower.org.

Rachel Herzing is a member of the Center for Political Education’s Community Advisory Board. Rachel has been an organizer and educator for the abolition of the prison-industrial-complex and for community-based interventions to interpersonal and state-based harm.

Rachel: I moved to the Bay Area, San Francisco Bay Area, moved to Oakland, specifically, which is mostly where I’ve worked. In 2001, moved to Oakland, specifically, to help start Critical Resistance as a national [00:03:00] organization. And so that was a very explicitly, I guess, abolitionist piece of work. And at that point was kind of the only thing going at that scale with those politics.

And I don’t really feel like I was thinking at all about transformative justice. I was thinking a lot at the time as we were building out the infrastructure, the organization, deciding who should be involved and who we would be most happy to work with, what it meant to belong to this organization, what our vision was, what our mission was.

As we were establishing all of that infrastructure for the organization, I was also spending a lot of time thinking about, you know, all of the what ifs that everybody wants to ask prison- industrial-complex abolitionists all the time, right? So it’s like you can’t show up somewhere without somebody being like, what about the murderers and the rapists and the child abusers? Right? So I was spending a lot of time thinking about the what ifs.

I was doing lots [00:04:00] and lots of research about things that people had tried, things people had tried in the United States, things people had tried globally to respond to harm without using something that was either or akin to imprisonment or policing or other kinds of punitive systems that deprived people of liberty.

So that had been on my mind a lot, and through that research, I eventually came across Generation Five. So many thanks to Generation Five for doing all that thinking work and imagining, you know, what a theory of transformative justice could be – and came into thinking about that. I was deeply influenced by Incite!, at that time, Women of Color Against Violence. You know, I was never a member of that organization, but as a fellow traveler, I feel like I was deeply influenced by what was coming out of that organization and really impressed by the really strong and affirmative stances that kept coming out of Incite! and that was kind of spurring, I think, the rest of us on to be braver and to [00:05:00] be bolder.

The other thing that I’ll mention that just popped into my head that I hadn’t thought of earlier is I was also in the early years of my time in Oakland, working with the Harm Reduction Coalition and doing education with them – training, you know, people who are interested in their network and talking to them about how you could support drug users to evade harm at the hands of the cops or imprisonment. So I was doing a lot of that work at the time. And the Harm Reduction Training Institute was a spot where I spent a good amount of time and was able to kind of also hone, you know, some of what would become messages that we would use later in Critical Resistance, and then even later in Creative Interventions.

So I was going along doing those things. Eventually ran into Mimi, really literally rode her coattails into Creative Interventions and spent some years doing that work as well.

Deana: Mimi Kim is a second generation Korean American, a [00:06:00] daughter of immigrants from a country still divided. She’s a co-founder of Incite! and a founder of Creative Interventions, one of the partner organizations of this relaunch of STOP / Stories For Power. She has lived in many of the cities featured in this podcast series. Born in Seattle, politically raised in Chicago, a long time Oakland person, and now living in Los Angeles.

Mimi: Hi, I’m Mimi Kim, and I am the founder of Creative Interventions, and so I have some history in the lead up to this moment right now. I had been doing anti-violence work for a long, long time, really since the late 1980s. And of course, you know, in the ways that all of us were doing this as kids, as high schoolers, and so on.

I was in the Bay Area starting around 1990 and actually had been working at the Asian Women’s [00:07:00] Shelter for 10 years, and during that time, I think kind of walked into that space already politicized, but really more so around my own critique of the anti-violence work that I had been really involved in since the 1980s.

At that time, I was really interested in trying to make sure that our communities, and for me in the late 1980s in Chicago, that meant the Korean American and Asian immigrant refugee communities that weren’t at all part of the battered women’s movement as we called it then, or anti-rape movement as we called it then. We just weren’t there. We weren’t represented.

And I was actually trying to get a job at that time. I was having a hard time because I didn’t have the experience, so therefore wasn’t gonna be hired. Therefore, when I finally got hired, it was because there was a recognition that there were a lot of Asian immigrant refugees coming into the United States. It was time of [00:08:00] a lot of Vietnamese, a lot of Southeast Asians coming, and people being aware that there had been a lot of sexual violence – and aware that a lot of people were coming into Chicago at that time – and that we had no response, no services, nothing. And so that’s how I first ended up getting involved.

It was a couple years later that we actually started a Korean domestic violence, sexual violence hotline in Chicago where there hadn’t been one before – called KANWIN. And then I really always wanted to live in the Bay Area in San Francisco. So I ended up coming there around 1990 and sort of begging Beckie Masaki at Asian Women’s Shelter for a job.

And they happened to have a job opening. I still had to go through everything. I did have to send in my resume, I had to go through all the interviews. But anyways, I did make it into Asian Women’s Shelter and it was really foundational, I think, for a lot of my work with the Asian immigrant refugee community.

And in Chicago, I had really, really [00:09:00] connected actually with the Black community, a lot of other women of color. And we were organizing a lot around challenging a very, very white dominated movement at that time. I mean, it still is. And came into my work in San Francisco with a lot of politicization from folks in Chicago. I have to say, it was really influential in who I was and how I understood race in relationship to violence, sexual violence, and domestic violence.

But I did that work for 10 years, and, during that time – 1994 is when the Violence Against Women Act passed, VAWA. So that was a moment where I really came to understand the depth of the collusion that we had with, we didn’t call it the carceral state at the time, but with policing, with law enforcement, with mass incarceration. I’m not sure that we were using that term at the time either. But it was so obvious. [00:10:00] Nobody had even told me it was part of the Crime Bill. That was not stated. I think it was really, like, repressed. It was denied. Nobody talked about it when they said, “hey, VAWA passed.” And when I found out, I was really shocked and stunned, honestly, and had very, very few people I could turn to who felt likewise. It was just like, we are just supposed to be really applauding, really happy about the passage of VAWA.

And I think that’s when I really started talking to just a couple people that I knew in the Bay Area at the time that felt likewise. There were so few of us. And, little by little I would say there were more of us that were talking, not necessarily locally, honestly, if I look at people that were involved in domestic violence and sexual violence, but people nationally. And a lot of those people were the ones that first came to Incite! in 2000, like Beth Richie, for example.

That was a moment that was very [00:11:00] influential. Rachel, your work, uh, Critical Resistance. I went to that conference that was also really mind blowing, really influential to me. And I think also, I think for a lot of Incite!, that was two years before we started a conference and we had a lot of overlapping people that were doing organizing across those two spaces.

I think that early intersection between our abolitionist feminist work, which we didn’t call it then, and the abolitionist work of Critical Resistance was very influential. And actually around 2001, I moved to New York and I really, really wanted to break away from the way that I had been doing anti-violence work. Like I refused to do work that was directly tied to kind of conventional anti-violence work. And I actually started going to those meetings that they had in New York around the Harm Free Zones. I connected to a lot of folks that I had known [00:12:00] in New York.

At that time, it was 9/11. And I was really looking for a radical community. I got together with a lot of folks that were at CAAV, for example. That’s when I met Ejeris. That’s when I connected with Kai, who was doing the Harm Free Zone work. And I started going to those meetings, which totally made sense, I think, because we were already trying to do that work through Incite!. And so I was immediately involved, not as a New Yorker, but as somebody who wanted to really contribute to whatever was happening in that space, in that time.

So, I think the work of Harm Free Zone, it was challenging, but it was also really an exciting time. I got to know Paula and other people at Sista II Sista. I know that we had a gathering of Incite! at that time, right in New York. And we had just a lot of really deep conversations around the kind of abolitionist work that we were trying to do locally – and figure out how we could really [00:13:00] plant the seeds, and plant that deep, and really try to do that work at a more local level.

After I left in 2003, I went back to the Bay Area and that’s when I had already known that Staci and Sara were doing the work of Generation Five. I had met them at another gathering, so I immediately connected with them to see what they were doing. We did a lot of thinking together. We did a lot of strategizing. We had a lot of meetings, and it was around the time that I actually had been searching a lot for, you know, who was actually doing TJ work, who was actually doing work on the ground. And I didn’t find a lot of folks. I actually thought I was gonna find a lot around that time when I went to New York in 2001. And coming back, I think, given my years of work, really knowing and meeting so many survivors of domestic violence and sexual violence, you know, from my own [00:14:00] experience in family, chosen family, community – I came to realize that if I was looking for other kinds of responses, that maybe I had to be part of that. And that’s when I started thinking that maybe it made sense to do it in an organizational formation, despite my reservations about that kind of form of the nonprofit.

I actually started that thinking that we would do something that would be temporary, that would take advantage of having a formation, that could consolidate some resources and take advantage of what seemed to be a kind of a “flavor of the month” that might be happening at that time, around some openness, maybe some money coming forward. Enough to open up a little office, maybe pay somebody – like myself – so I didn’t have to completely do that work for free, you know, that I could actually devote some time and create a space where other people could come together to really experiment.

Some things came [00:15:00] together, and in 2004 is when I got together with some other folks. I knew it wasn’t just me that thought something like Creative Interventions might be a good idea, but there were other folks saying, “okay, I don’t necessarily wanna do it in my organization whether that be a nonprofit or a political organization, but I wanna see what happens. I’ll be part of that. I wanna be part of that. Let’s see what we can do in this next period of a couple years” – which, of course, extended into more years than that.

And that’s when Creative Interventions started. And we had a mission. You know, we had some work that we wanted to do. I, of course, thought it was just gonna take a couple years, but not surprisingly, it took a lot more. And here we are, still trying to do this work and still experimenting. The STOP Project was one of the first initiatives that we did as part of that work, because we were actually really pretty underground in trying to do interventions to [00:16:00] violence that we called…I mean, we didn’t really call them anything.

At the time, I wasn’t really crazy about using the term transformative justice. It just sounded a little bit too lofty. And justice? What the fuck are we talking about? Let’s just not even call it anything except that we know what we wanna do. We know we want it to be collective. We know we don’t wanna use the cops. We know that we probably can’t even rely on any service ’cause they’re gonna think this is a terrible idea. So let’s just see who comes forward and who needs something. And we had no toolkit. You know, we didn’t have a recipe, we had nothing, but we had some ideas about values and principles, and that’s what we started with.

Deana: Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is a non-binary, femme, autistic, disabled writer, space creator, and disability and transformative justice movement worker of Burgher and Tamil Sri Lankan, Irish and Galician/Roma ascent. They’re the author or co-editor of 10 books, including The Future [00:17:00] Is Disabled: Prophecies, Love Notes and Mourning Songs, Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement, which was co-edited with Ejeris Dixon, and The Revolution Starts At Home: Confronting Intimate Partner Violence in Activist Communities.

Raised in Worcester, Massachusetts, and shaped by Toronto and Oakland, they are currently at work building Living Altars/ The Stacey Park Milbern Liberation Arts Center, a disabled QTBIPOC writers’ space and accessible retreat for disabled BIPOC creators. They still believe the future is disabled and that disabled and neurodivergent BIPOC survivors are who is saving us all.

Leah: The projects I was a part of in the early 2000s through the 2010s. The first one I wanna name is I was one of the co-editors with Ching-In Chen and Jai Dulani, and Sham-e-Ali Nayeem originally, of this project called The Revolution Starts At Home: Confronting Intimate Violence in Activist Communities, which started [00:18:00] off as the four of us being pissed off about our abusive exes on a live journal thread at our day jobs, and became a zine, which then became 108 pages, which then became a book.

We started out just wanting to collect stories of people who had been abused in Black and brown and queer and trans and radical communities who didn’t go to the cops to try and deal with it. And then as it evolved with the movement, it also turned into a thing where we were like, we wanna start documenting the ways that people have intervened in violence without the cops.

And it was really about like just gathering stories in a zine format as an organizing tool, which is very early 2000s because there weren’t books about abolition or transformative justice then. There aren’t a ton now, but up until like the early 2010s, I was like the way that I knew most people knew about stuff was through zines, right? Like that was a really…DIY media was really important.

I was working on Rev at Home when I moved to the Bay in 2007 and doing a lot of just kind of independent, you know, being known as someone [00:19:00] who is a survivor and getting a lot of phone calls from people who are like, “I heard you had a situation. Can I talk to you?”

And then when I moved to the Bay, that’s when it got more organizational because there were organizations doing this work, which was really different and which I hadn’t run into. So some of the things I was involved in once I moved to the Bay were, I worked at for like nine months at generation FIVE, which was an organization that was founded by Staci Haines in around, I think the year 2000, which had the goal of, the very, very chill, non casual goal of ending childhood sexual abuse in five generations without using the police or prisons – and simultaneously dismantling all systems of oppression. I was on the program team for under a year.

And I also worked with CUAV Communities United Against Violence, which is a long running San Francisco queer and trans anti-violence organization. They had this revolution around 2009 where they were like, we are just gonna have all of our anti-violence work [00:20:00] be based on a transformative justice model. We are not gonna work with the police anymore, like if a survivor wants to go to the cops, we’ll support them. But they got really deep in doing political education and cultural work and interventions using TJ. And one of the main ways this played out was they had these things called “safety labs” where people could get together and just talk about transformative justice and do role plays and read stuff and practice it. And then they, for a couple years, they had these annual festivals called Safety Fest. That was like three weeks long, 25 different events, parties, club nights, workshops, all of this stuff. And it was all based around TJ. And I did a lot of work with that.

There are two projects that I worked with that were not primarily TJ, but I’m gonna name them ’cause they were important. With Cherry Galette, I co-directed this queer and trans people of color arts collective and tour called Mangoes with Chili, which is kind of lost in the MySpace era now, but was a really big deal back then. And I mention this ’cause we were doing like burlesque and performance art and spoken word, and [00:21:00] we were talking about TJ in it, in the club. And so that’s one thing.

And then I also got brought into Disability Justice around ’08, where I went to a Sins Invalid show, which was pretty much the foundational collective of disability justice, and got my mind blown and then got invited to do work with them. And they were doing, they were both doing some of the first work I’d ever seen that was by and for disabled Black and brown people about our experiences of violence as disabled BIPOC. And also on a personal level, it kind of opened a door for me to be like, oh yeah, my experiences of survivorhood are very much intertwined with ableism.

I was one of the people who helped organize this 2010 North America wide gathering of Black and brown. I think we were like, they don’t have to be queer, but they can’t be cismen who aren’t queer. That like, CA / community accountability, transformative justice gathering in Miami, where we were like, Mimi, you were like, I just wanna get us in a hot tub someplace where we can talk about our problems. And Rachel, you were like, I hate a fucking hot tub. And then like, people on the East coast were like, we got some grant money. And then all of a sudden it was at [00:22:00] a hotel and then it got complicated. But it was one of the first places that we were like, let’s get these collectives together and talk about stuff.

And I also was involved in the creating safer communities and growing safer communities tracks at the Allied Media Conference in 2010 and 2011, which were places that different collectives came together to just share what we’re doing about CA / TJ.

Deana: I personally love a hot tub, and that’s the type of gathering where I wanna be.

So I also wanted to ground our listeners in what was going on in the San Francisco Bay Area at the time you were working on these projects. So what was the historical context in your communities when you were doing this work?

Rachel: The first thing that pops to mind is the war against Iraq, against Afghanistan by the United States. At that time I was working mostly in issues of anti-prison industrial complex stuff, and there’s a thing that happens frequently when there’s a war on, right? That the violence of policing escalates, that imprisonment escalates.

I remember being in [00:23:00] Oakland on September 11th. I had just come back from the World Conference Against Racism. Really, really just I think days before September 11th happened. We Critical Resistance have all kind of people in New York. I’m trying to find my people. I had just moved from New York to the Bay Area.

You know, one of the first things that happened in California, and I think in other places as well, is they locked down all the prisons. That lasted for a good long time. It was impossible to get any information in or out of prisons for a very long time after September 11th, and then we see the waves of criminalization.

You know, thinking about New York, what you were mentioning, Mimi, just kind of how locked down that city was, and how hard it was to move around, especially lower Manhattan. And heaven help you if you’re brown, or heaven help you if you look to some cop like you might be Arab or South Asian. And that really created a serious tenor for the work that I was doing at that time.

Then we see the [00:24:00] passage of IIRAIRA and the Anti-Terrorism Effective Death Penalty Act, you know, and after Oklahoma City, right? So there’s all of these ways that we see the kind of mounting and growing state apparatus to enforce law and to repress, you know, kind of the movement of so-called dangerous people, right? Which we know means us, right?

So we see the expansion of the Department of Justice, the consolidation of all of these departments under the Attorney General. During this period, we see the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and all of this stuff was in the can, right? As quickly as it got rolled out you could tell that somebody had it in the works, waiting to release it. And I think that has really, really, um, impacted going forward how the borders get enforced, but also how policing happens across the United States. Who goes to prison for what, you know. And attached following the kind of legislation at the hands of Bill Clinton, we see kind of the rollout of all [00:25:00] this other stuff. Mimi, you probably will remember, you know, New York, pre September 11th, there was very, very lively, vigorous, dynamic anti-policing work going on. And America’s mayor, Rudy Giuliani, was really on the ropes back then, and was really having to do a lot of accounting for the violence of the New York Police Department.

September 11th happens, it’s like a – a switch flips, right? I remember coming right after, and suddenly it’s like “all praise our heroes” murals all over that town. Banners hanging across streets all over lower Manhattan. Thanking cops, praising cops. And a police and military presence everywhere. And so I think that context really did shape a lot of how I thought about entering into the work of that period that we’re talking about.

And then I also think, you know, I’ll just mention, I don’t think it can be overstated, the relationship between the organizations that became Incite! and [00:26:00] Critical Resistance, and the kind of back and forth. And the development of that very important statement. Critical Resistance, Incite! /Incite! Critical Resistance, depending on where you start, I guess, joint statement on violence and non prison industrial complex responses.

Deana: Yeah. I’m hearing a lot about the impact of 9/11. Leah, how did this period influence your political work?

Leah: I was a college student in 1995 organizing against Giuliani in New York. And I remember the vibrancy of that time, the vibrancy of squatting communities in the Lower East Side, like, and I remember demonstrations where like I literally got arrested at the 13th Street Squad eviction, which was five buildings that had been held in the Lower East Side for two decades. That Giuliani brought a tank out to evict, right? And like two weeks after, or before that, I forget, we organized a demonstration that blocked all of the bridges and tunnels in and out of Manhattan at rush hour to protest, in this like 40 organization coalition that was like ACT UP, [00:27:00] CAAAV, all of the anti-police brutality organizations that were around, like, to protest Giuliani’s budget.

And they were pissed. They stuck us in the tombs for three days. Like all the white men in ACT UP were like, oh, don’t worry, we’ll be out in two hours. And they were like, no, fuck you. It’s a lot of Black and brown people. We’re gonna punish you for this. I think about that a lot where I’m like, we didn’t have a single cell phone and we didn’t use the internet. And they did not know we were gonna do this. They were surprised by it. And we fucking shut the city down. It was that kind of militancy. And I was 20-years-old, learning from this intergenerational movement, and so were a lot of people.

And then when 9/11 happened, like, thank you for bringing back the war, because I had left the states in ’96 for a lot of reasons, including to get away from my abusive, really intense family. Like I literally left the country and married my comrade. And so then when my parents tried to put me under conservatorship, they couldn’t because it was like husband plus national boundary. That was a real bold move on my 21-year-old [00:28:00] ass’s part.

But September 11th comes around. I’m in Toronto as a young mixed race Sri Lankan white person. And we just saw, you know, everything you mentioned, Rachel, and like the Patriot Act was huge, like all of the repression. And we were coming out of this period in the late ’90s where we were like, oh my god, anti-globalization. Like, we’re gonna fight to win. There’ll be massive demonstrations with puppets and we’re gonna take over. And then it was like Uhuh. No, the empire has other things in mind.

I was a Torontonian baby abolitionist in the late ’90s during a time where the A word was not really being spoken. But I was in Toronto in a collective called Prison News Service that had been active all through the ’80s and ’90s. And Jim Campbell, rest in power, who was like a working class white queer prison organizer. He was like, when the repression was happening in the ’80s and ’90s, we north of the fake border were doing political prisoner work. We were doing stuff around Black Liberation Army folks were locked up and people like that. When it was too hot or too many people were dead or disappeared in [00:29:00] the states to get that word out.

I remember like Helen Luu and a whole bunch, it was a collective of like Black and brown, younger and older feminists who started Colors of Resistance. And were like, we’re gonna have a pan POC movement against the war, against empire, and against repression. And there was so much organizing. I was part of a radical working class South Asian wave of organizing that most people don’t remember.

And I should mention briefly that, you know, I mean my entry point to this work was that I fell in love with somebody when I was 21, who was also mixed race, working class immigrant kid. Their parents had been revolutionaries in Chile, armed communist revolutionaries who’d suffered under Pinoche, survivor, who I was doing all my organizing work with. And then they became abusive. And I had to figure out what to do without the state, ’cause they were my immigration sponsor among other things.

There were like webs we were trying to weave across the border, around migration, around things like the Safe Third Country Act. Around repression in general. And there was this sense of this [00:30:00] growing, not led by white communist men, you know, like pan Black and brown and indigenous, very queer radical movement.

I remember in the year 2006, it was one of the first big immigrant rights protests on May Day, right? There’d been a revival, and it was one of the first ones where there was a contingent led by queer and trans undocumented BIPOC people, and this was new. And a lot of us were queer and trans people being like, fuck this. Like our radical sexuality and gender politics are not separate from this movement, and we’re not gonna be shut up by heterosexism. And I think that that’s really important in the context of why community accountability and transformative justice, abolitionist feminism happened. Because so many of us were the queerdos who’d either been in or witnessed some fucked up shit happening. And we were like, no, not again, ’cause we actually remember the sixties and we remember the violence that was in radical Black and brown formations.

So I moved to Oakland in ’07 and as like the queer brown femme, like, it’s like we talked about Oakland like it was the promised [00:31:00] land in that period. Like this was when it was not common to have QTBIPOC space everywhere. And so it was a real mother lode of like political and cultural organizing and community. And so when I moved there, it was after I was part of Voices of Our Nations, which was a writers of color residency. Again, one of the only ones of its kind, it was based in the Bay.

And I would go there and I would meet other like QTBIPOC weirdo writers. And we were like, it’s so beautiful. It smells like jasmine. Holy shit. Oh my god. There are all these dance parties, there’s all these political people. They’re not all white. Fuck yeah, let’s move here. And it felt like there was a wave of us that all convened on Oakland.

And what I wanna say is that it felt like such a time where there was so much hope. There was so much pleasure. It was affordable to live in Oakland. There were so many poor and working class QTBIPOC folks who did not feel safe in our home communities, who were like, oh, I can go to Oakland and you can be a queer and trans, Black and brown person there. Like there’s so much community.

And Oakland did [00:32:00] not feel gentrified. I mean, all of North Oakland was Black as fuck, and Korean and brown, and there was not a single Tesla on the street. And I would say too, because everything was much more affordable, it made space for people to be hopeful and curious and have time to just hang out.

The pleasure was really important. Like, it just…I cannot overestimate that for me, anyway, it felt like the people I organized with were also the people I partied with and that we would be on the dance floor at like Mango or Butta, all of these very long standing like queer women of color, as was the style at the time, clubs. And there would be, I would see like older, you know, in their forties and fifties and sixties, queer women of color dancing there, ’cause they were at three in the afternoon and it was $5 and there was barbecue. And I was like, these are also my comrades. It was one of the places where people talked about healing and stuff that fueled both the really hard work we were doing and gave us a sense of possibility.

It was wide open. It was just like, you are a queer woman of color or a BIPOC feminist. Great. Come to this meeting. We were really fired up from [00:33:00] Incite! and we were like, we’re all together and we’re just gonna take on the world. I often think that right now it feels like a very grim time ’cause it is, and it’s hard for me to bring to people…Back then we were like doing like abolitionist strip numbers, like we were into having fun with it. And people were really excited about transformative justice and community accountability. And because it was wide open, like anyone could come to a workshop or a meeting and be like, all right, I’m gonna start doing this. And there was complexities that, but honestly it just felt like we were growing so quickly. So yeah, TLDR, like joy and pleasure and affordability in the teeth of the dragon.

Rachel: You know, Leah, as you were talking, I did think of one other thing that I think is really, really crucial historical context, and I so appreciate you bringing up all of the pleasure and fun because I miss that about Oakland. I’ve left Oakland couple years ago, and I think the experience of this period that we’re talking about is also marked by the kind of ebbs and flows of tech, right? So when I [00:34:00] came on the scene 2001, it was impossible to find a place, right? Like there just were no places. And the like three places that were listed, you had to essentially fist fight like white boys with wheelbarrows of money who showed up on site ready to be like, “I’ll pay for the full year.” And the housing market was just kind of the never ending story of the Bay Area. I feel like it really does color so much about people’s experiences there, and I think we’re in another period where it’s hard to live there and housing is, is part of that story, but that is definitely fueled by the kind of boom and bust cycles of tech.

Mimi: I think in terms of the context, what I’m really hearing from you all and remembering is how much our work was also based on relationship. And whether it was because we’re part of an organization, whether we were employed by the organization or like you were saying, Leah, or whether we just identified with that organization or created an organization out of nothing, they had [00:35:00] meaning and they had materiality at the time. One of the things that I was really thrilled about being able to do in getting some money for Creative Interventions is that we could actually pay for a small office. It had a little part that you could lock up, so you could stick your computer in there and lock the door, and then it had a bigger space where we just had a bunch of chairs that I got from Target. It was like, a circle of chairs where they were kind of rocky little chairs, like they were kind of cushy. We had like a nice couch. And the idea was we are gonna sit around, whether it’s just hanging out, whether it’s planning something, whether it’s a meeting, whether it’s folks wanting to come together ’cause their friend is getting beat up and they wanna figure out what to do. It was a space where you could just hang out. We didn’t have any hours. I mean, people would come and they would not stay for like a 45 minute or an hour. I’d be like, folks would stay there like [00:36:00] three, four or five hours, ’cause we didn’t have appointed times for so much of what we did.

I always had like many cans of sour cream Pringles on hand. If people started getting hungry and needed a snack, I remember there was like a little sink. And then we could crawl out the window and go out into a, I don’t think it was exactly a patio, but we made it into a patio. Yeah. And then who was upstairs? Critical Resistance had their office upstairs.

Leah: Right? That was the movement building.

Mimi: It was a movement building.

Leah: Gen Five, when they did their training, they used that building. That’s where I first ran into it.

Mimi: DataCenter was up on the ninth floor. Yeah, there were a lot of us that would, even if you didn’t have your office there, be coming there for a meeting.

I think the spaciousness of just hanging out like leah was talking about, was such an important part of experimenting, you know, not having to have like super, you know, get this done in an hour like so much of our world right now over Zoom, you’ve got an hour, you’ve gotta have everything figured out, gotta get off and [00:37:00] go to your next meeting.

We just didn’t have that kind of culture at that time, and affordability was a huge part of it. I think there was this idea that your political work and your paid work, you hopefully get paid enough so that you could pay your rent, but that we were gonna take care of each other and make things work out. Because it was really the relational work and the political work that was really important.

And the pleasure. I mean, that just was kind of assumed that you were gonna have time to, to hang out. I mean, I’ll say like we always had wine and whiskey around because if it was gonna like morph into something that was gonna be longer and go into whatever time, like, hey, we knew we had things around to make it into a social time, if that’s what was needed. And social time and political time was, you know, there was a fluidity there.

At the time, I just, for me, I remember also knowing, in part because we did not want to be there as a permanent 501(c)3. a nonprofit, that that time was gonna be precious and it was gonna be [00:38:00] over. And that we were gonna have this period where we were just gonna be able to really connect, hang out.

I remember Kalei came and talked about the work that she was doing in Hawaii. I remember Kabzuag coming from Madison from Freedom Inc. and meeting Kalei, and Kabzuag was still saying, oh, we did some of the work because of what Kalei was talking about, what she did in Hawaii. And then talked about what she was doing in Madison, which was really radical work.

We worked hard, we worked long, but we had fun. We always had food. Hanging out was just very, very, very important and assumed.

Leah: Honestly, when you’re talking about the building, like one thing that popped in my mind was like, and it’s not true of everybody in the movement, but, I would say a lot of the folks that I was in relationship with were people who were also coming out of what at the time was this very new upswing within QTBIPOC community of being poly and talking about kink and like being part of like, you know, sex radical culture.

And it felt like that [00:39:00] was for at least some of the people I was organizing with, we were also in those spaces and it’s part of how we built relationships. And also sometimes how shit got complicated where I was like, well, that was a funky breakup and now we gotta end prisons together.

Deana: Yeah. I keep hearing these themes of community and relationship building and how they laid a foundation for all of your work together.

So now I wanna move us into your favorite success stories and what made those success stories possible.

Rachel: I am happy to offer one, which is a little meta, I guess, for this situation, which is I, I feel like launching the StoryTelling & Organizing Project kind of as STOP. It…when I came on the scene at Creative Interventions, it was still called the National StoryTelling Project, and Mimi had been collecting stories and talking to people. But I feel like, you know, we had this idea that we could really amplify it, and, you know, make that the more public face of Creative Interventions so that we could do some of the [00:40:00] experimentation and helping people with their situations a little bit more underground.

And I think launching that and having that be a, a more public thing, you know, we showed up to just return to what you were mentioning earlier, Leah, we showed up at Allied Media Project. We talked about it there. We wound up making hubs around the country and across the planet, you know, to help collect stories, but also to help think about how to use stories in real life, right? And so that feels like a really big success to me. And that obviously didn’t happen all at once. That happened over some amount of time. But I feel good about what we were able to do in mobilizing those stories to help people imagine that they could take steps in their everyday lives and to acknowledge the fact that all day, every day, people are trying stuff without the cops. People are trying stuff without trying to lock anybody up, and that it’s possible.

Mimi: Part of our success was the way in which we just kept plodding along. And I’m saying [00:41:00] dd, not tt. Well, we did that too. We knew that we had to do a lot of things with a lot of people and experiment with a lot of situations if we were gonna make sense of it in a way that was gonna have more usefulness to the world out there. And so that was part of the intention for the StoryTelling & Organizing Project, for having a lot of different stories. We still have the stories up, but they’re very, very different. I don’t even think I could have imagined how different they were gonna be before collecting those stories.

And same with the ones that we did, many of which you won’t hear about because we did not get any agreement to share those particular stories. But what we got was a takeaway. We didn’t start constructing the toolkit, and what some of you will know as the Creative Interventions Toolkit, which is almost 600 pages. You know, I think the ideas came out of it, obviously from day [00:42:00] one of the work, but it was really after we had decided that we were gonna start closing out that experimental phase and really start sitting back and looking at all of the information we had collected. And that was a lot. We actually documented just a hell of a lot. And from that, parsing it down to something that’s whatever, 600 or 900 pages.

That was like an accumulation, but it was also distilling a lot of different stories that we had and Rachel and I were there. Rachel, you were there from almost the beginning, if not the very beginning of the actual work we were doing. So to know that Rachel, Isaac, all the people that were part of the team were really there for quite a long time, and I’m talking years, to collect stories, to learn from each other. We used to get together every two weeks to share what we had been learning, to really ask ourselves, [00:43:00] “is this what we’re trying to do?” And that was, do we want something collective? Do we want something that really holds the humanity and the possibilities of transformation for the person who caused harm? If we could even determine exactly who that was, ’cause it wasn’t always clear.

Were we doing something that wasn’t gonna be held in an agency with professionals, but actually could be information that goes out to anybody. And that is anybody who is facing a situation of violence, you know, no matter who they are, whether the person who caused harm, the survivor, their friends, family, community, and have something that they can get that would be helpful for them to be able to frame and understand what’s even going on. Because when you’re involved in violence, it is, it’s chaotic, it’s confusing. It is for anybody. So it brings you a little bit out of yourself into some thinking that people did collectively, and we hoped it would be helpful. I’m talking about the toolkit now. The stories certainly have been [00:44:00] helpful. We still get feedback constantly from people that I’ve never met before that they used it, and it was helpful. That, that is really, I mean, I have to say, I still get surprised every time. And I’m really grateful that I was able to be part of something, you know, with all of you, ’cause Leah, you were there too. You, Rachel, you were there, and so many other people. To really put our energies, our minds together. Our politics, our passions, our hopes.

And I was unrelenting, and I still am, in the belief that we are doing the right thing. It might be imperfect. We definitely fuck up for sure, but how are you gonna create something without doing that? You have to go through those steps. As much as things that I had hoped would happen, didn’t always happen. Sometimes people just met and decided that they didn’t wanna get, go any further. I think, I think what we found is just the fact that they were able to meet, or [00:45:00] that they were able to not just rely on kind of the usual, either nothing, or going to calling a hotline that was gonna tell them something that wasn’t what they wanted to do. That in and of itself, I know, has been helpful to people. But of course we wanna do more than that.

And I think, at this point, there are more successes that came out of some of the very beginning work we did. People come and say, “Hey, I tried something and it worked really well” – and I am so pleased to know that people took some of this information, took it and ran with it and made it what they needed and have created new things.

That’s exactly what we wanted, was never about, and I hope it wasn’t about, “use this tool because that’s what you’re supposed to do, but. If it works for you, if it helps, please do.” We also really work towards knowing that someday we weren’t gonna have any money, and that no matter what, if we didn’t have money, [00:46:00] you weren’t gonna lose your access to that toolkit.

So if you want to buy the book from AK Press, that’s great, because it’s beautiful and I personally really love having a book available. But if you want it for free, it’s there in PDF. It always will be. The workbook now is in a Google Doc. If you wanna take it, rip it off, make it something else that you need, that works for you, put your names in it, um, that’s the work of also STOP. Nobody has to pay for any of that. And I think the fact that we really were intentional about documenting and sharing anything that we thought was valuable in what we learned and made sure that it was gonna be available for free beyond a formation, beyond a penny coming to us. That was really, really important. And I would say that I feel like it’s been a success, and it continues to be.

Leah: This is captain obvious, but it’s just striking me. I’m like, oh, all of our stuff is about the [00:47:00] power of stories to change the fucking world. Like, I think with Rev at Home, like there’s some similar stuff that feels successful to me.

We started working on this almost 20 years ago. That is wild. And you know, I mean, for me, like I was a baby riot girl, baby punk, you know, not the cool kind, just the very depressed, disassociated, nerdy brown kind. You know, I was too shy to go to shows a lot, but like I would get all these like baby incest survivor zines in the mail, and that helped me even before I was out about being a CSA survivor.

And they were written by, you know, 16-year-olds who were surviving the abuse still, in their family of origin’s home. It was really powerful and it was all of these young survivors just like soaking a stamp in rubbing alcohol and mailing our shit to each other.

I feel like that’s part of what Rev at Home was about for me, was I was like, I knew what it was like to be so isolated as a survivor, both as a young person, as a child, and as a young adult, and where, you maybe can’t, I mean, I know a lot of times we’re like, okay, yeah, talk to your friends, talk to your community. [00:48:00] Sometimes the hotline’s not enough, and you don’t feel safe to talk to your friends, but you can get a book outta the library or a zine and read some stories that you relate to and that gives you some ideas of what to do. That’s lifesaving.

I mean, we got an email from Bangladesh a couple years ago that were like, “we hope it’s okay, we translated the zine.” And I was like, oh fuck yeah, like, and also I’m amazed.

So I’m grateful to everybody who told their stories, and I’m grateful, as more and more as time goes on, that in the book version, there’s so much documentation of organizations that were doing work in like ’07, ’08, ‘010, that are lost in the midst of time.

You know, that’s one, I wanna say on a more intervention wide level, I do have a very sweet memory of going on the second tour with Mangos with Chili. That happened right after CR 10. And this is one of the ways that, you know, in a very nitty gritty way, relationship supported all these movements. And so we are in this van. It was the Queer Borderlands tour. So we’re very much in the tradition of Gloria Anzaldúa, like we’re going from Arcata all the way [00:49:00] through Arizona, SoCal, Arizona, New Mexico, and then up to Colorado. Got stopped by ICE, you know, almost got arrested because someone had weed, all of this shit. And people were just coming out to like random queer bars in San Diego to see some titties and some emo poetry.

But we had a zine table and that zine was on the table, and Gen Five’s statement zine was on the table. And we just had a sign that was like, abuse and community zine, $5. And that was what everyone wanted to buy. And these were like bar queers of color. Like this was not like, you know, “the cadre” necessarily, like this was just like ordinary folks were so hungry for it and I’m really proud of that.

I think we all said like, yeah, we became these people that everyone was telling their horrifying abuse story to, and then you’re walking around with all the shit in your head wanting to explode. Maybe not everyone said this. I felt this way. There was a period in Oakland where that was happening to me a lot, and I didn’t know it, but I was starting to get burnt out, and I was just like, the rule of the day was like, hold it in confidence. And I was like, right. But I was [00:50:00] just like, I don’t know how much more of this stuff I can hold in confidence before my brain explodes.

And something that happened multiple times was that person A would come to me and be like, my ex who I just broke up with raped or beat me, and I wanna tell you. And I, I heard that you’re the abuse lady, so like let’s talk about it. And I’d be like, okay, ’cause I’ve been there, and they were just like, I know how hard it is to reach out. And we would talk, and then person C would hit me up and be like, oh, I’m dating person A’s ex. But they wouldn’t know any of the abuse.

And they’d be like, oh, can we come to the orgy, the party, the film night, the book club. Some of which was in my house. And I would just be like, oh god. This was one of the times where I was like, I don’t know if I’m doing the right thing. But I was just like, I feel the need to pass this information on. And I would talk to person A and be like, “hey, person C is now dating your ex boo. Do you want to tell them? Do you want me to tell them? Is there any way that we could share this information?” And sometimes there would be a facilitated meetup between the former partner and the current partner. [00:51:00] And sometimes people would be like, “I’m not ready to say anything, but can you share it?”

And so then I would be in this awkward as hell position of going to person C and being like, “Hi. The person you’re dating who you’re in like new relationship energy with. Yeah. So I have some information from one of their exes. They gave me permission to pass on. No, I can’t tell you who it is. Yes, I know this is awkward.” And I would go back to the values where I’d be like, “I know this is awkward. I’m doing this because I care about you and I wanna give you this information. And you can ignore it. You can do with it what you will. But I would be remiss if I did not pass this on.”

And it would be really awkward. And person C would often be mad or upset or be like, “what do you want me to do?” But I gotta say, there were multiple times when person C came to me two weeks, six months later being like. “I felt weird, but thank you so much because I had a conversation with that person. And sometimes that person would be like, yeah, I did do that stuff and I haven’t known what to do about it, but let’s talk about it.”

Or honestly, person C would be like, “I started seeing red flags, and I was talking myself out of them, and I would’ve kept minimizing them. And then what [00:52:00] you shared, I started noticing, oh yeah, that’s what they’re doing. And I got outta the relationship before the violence happened.”

And like, you know, the saying is, “femme gossip saves lives.” And that’s complicated because like all gossip can either save lives or, if it’s not held well and accountably, can really mess shit up. But sometimes that information sharing is really important. And I’m proud that even when I was at maybe some of my most burnt out and like, I don’t know if this is the right thing to do, I did the best thing I could to facilitate information in a way that had values so that people could make decisions. Right? And could practice being like, do I set this boundary? Do I wanna stay? Do I need to leave if there’s even a hint of it, right? And then sometimes person A and person C would like become friends and like build that connection. And that was really sweet. Like, I was like, maybe the rapists don’t win all the time.

Deana: You know, that’s a great example of how successes often go hand in hand with challenges. What are some other challenges that stick out to all of you? And can you talk a little bit about how [00:53:00] those challenges grew your work?

Rachel: One thing that you reminded me of, Leah, that I think is worth saying about our context too back then is that the Bay Area is small, and it is a blessing and a curse, right? ‘Cause there are all of these times when you can build these networks across organizations and across even like the geography of the Bay or whatever. But there are also all of these things that I’m sure each of us know about all kind of people in our very, very small community that we were trying to figure out what to do with and um, and it’s hard to get away from the people that you know stuff about in a setting that small. And I think that it fueled lots of stuff, but it also came with some challenges, too.

Mimi: I mean, we definitely talked about how much is somebody’s story, their story, when obviously they’re talking about something that’s relational. and they’re talking about other people. You know, what’s the balance there between them consenting themselves to share [00:54:00] something – and it is their story, even if it involves other people.

But I think it’s a little bit of a different challenge than the one that I think Leah was talking about in terms of, you know about violence, how much do you share? How much do we expect somebody to share if they were asking for accountability? I know a lot of times we were, at the time, and I think it still happens, you know, asking people to share across publicly. What does public mean?

And that’s really shifted since that time. But even at that time when we had emails like, were they supposed to email everybody they knew? What were the boundaries? Do you email it to everybody you know, and you email it to other people that carry a lot of blame, shame around violence that we were really trying to counter?

I think this is still a thing because people still have a huge amount of shame around being a survivor, around being somebody who caused harm, around anything around violence in some ways, to me, is surprising how little we’ve moved away from [00:55:00] the kinds of shame that we carried and the kinds of lack of understanding of what disclosure is gonna bring about. Because you can run into anything from the usual, right? Denial, dismissal, that person fucking deserved it, to – I think, the calling out. I mean, that could be a whole nother, you know, five hour conversation. So I think that was a challenge then.

I do think that we have been creative around that. I love the story that you shared, Leah, about the kind of thought process you went through and the kind of search for ethics around that. What’s the right thing to do? And deciding that that was something that was your responsibility to share. And seeing the different responses that people had to them and having the difference between an immediate response of being angry and possibly grateful later on. I mean, think those are things that we continue to grapple with, and I do think that we were [00:56:00] much more breaking kind of new ground at the time in terms of our conversations around that and trying to understand the nuances around that and the problems.

I think it’s a long time later, and I think we’re still grappling with that. We also have a really different tech culture, obviously, social media culture that makes things not the same as they were when we were doing this work more actively in this period we’re talking about right now, I know for me is a challenge in this current moment too.

Rachel: I think a lot of what you shared, Mimi, is still really, really resonating for me. I know that my default against my better judgment is still confidentiality, whatever that means. You know, I think the lesson inside of that, that I’ve learned over and over and still don’t deal with appropriately all the time is that confidentiality creates a whole lot of problems.

If you wanna transform the situation, probably somebody else is gonna need to know besides me. [00:57:00] And if I’m not foregrounding our conversations with the fact that like, I can’t keep everything anonymous. I can’t keep everything confidential, and probably there’s not a reliable means in this period, contemporary period for doing that, then I think I create a whole lot more problems for myself down the line.

You know, not to let myself totally off the hook, but part of my default now is that things move so quickly via social media that I feel like if I don’t contain it, if I don’t say, “you can’t share this.” Then it has the possibility to spiral completely outta control.

But in terms of lessons, I think that’s a good problem to be inside of, right? Is to figure out how do we share stories in such a way that, you know, we’re not adding on harm, but we are holding people and supporting people through what is potentially incredibly difficult, right? So I’m gonna share your story out of, you know, respect for [00:58:00] you because I wanna get help. Or, I think it’s important for your community to understand that you’re grappling with this so that they can offer you all kinds of support. And I would say that’s true, whether we’re talking about people who have experienced harm, or we’re talking about people who have caused harm.

In terms of how to move forward. I think more and more boldness and more and more confidence in sharing more stuff upfront, in ethical ways, you know, in the ways that you were describing Leah, using some of those calculations is really, really important.

You know, the other thing that just struck me is also the idea of how we deal with the increasing popularity of so-called transformative justice. And, you know, how we help people use those skills and practices and tools well, right. So you all might remember in the early teens, a lot of people were wilding out [00:59:00] saying they were doing transformative justice processes and doing all kind of foul shit to each other under the name of transformative justice.

And then writing, you know, manifestos or publicly denouncing each other. And then also saying that transformative justice was bunk and didn’t work because it didn’t have the punitive outcome that they hoped for, right? And, you know, a lot of the very, very hard work that we’re talking about from those earlier years just got kind of demolished.

And I worry about that around prison-industrial-complex abolition, too, as that gets popularized and kind of anything goes around those politics, that then when it becomes a shambles ’cause people don’t do the politics well or they don’t hold themselves accountable to kind of rigorous standards around those politics, then it’s like, well that’s kind of bullshit politics.

And it’s like, the fact that, you know, you didn’t do it well doesn’t mean that it’s not good. You know, at the same time, I don’t wanna be the [01:00:00] arbiter of what’s good and not good, right? I think that’s not appropriate for me to be, even if I wanted to be, which I don’t. And so I think that’s an ongoing challenge. And I think there are a lot of lessons inside there that we can draw across to different things as they get popularized, but also to, you know, transformative justice, itself, as it has this renaissance, or whatever it’s having, you know, of people saying, “oh, I’m doing transformative justice,” to really think about like, “what does that mean?” And how can we amplify the practices and ideas and tools in ways that prolong its ability to live and do the kinds of things that it does best.

Leah: Awww, Rachel, you beat me to it. Thank you. Yeah, all that like, oh, we were so open and trusting and working together. Yeah. And then there came, there was a period where like it wasn’t cool anymore. It wasn’t like a nice vibe. It’s like everyone was at each other’s throats. And I think there’s a number of reasons for that.

And so the challenges I would share, it’s like, yeah, the, the popularization. And [01:01:00] before that, it felt like there was no ego. There was no money in this. No one’s gonna give you a big prize or whatever. We were all just kind of selfless in the trenches doing this work out of love for real. And then I didn’t anticipate that the visibility that I would get, that we would get as some people had been doing organizing for a while would mean that people took shots.

I mean, I remember when somebody was like, “oh, you’re a rape apologist.” And I was like, “I’m sorry, what?” I was gonna go and present at Smith College in 2015, and I got a call being like, oh, the survivor community of Smith might do a picket outside your talk at the disability justice conference. And I was like, I am a survivor. I’ve survived shit that would curl your hair or make it all fall out. And they were like, “oh, they read a blog that you did once 15 years ago where you said that no one should ever call the cops.” And I was like, “I never said that. I said I couldn’t call the cops because it wasn’t safe for me.” Right. Don’t get it twisted, but you just did. And then there was no picket line. And I was like, oh Jesus. And I think that a lot of us in the movement, [01:02:00] we all had experiences like that. and we were not prepared for it.

Backing off of that, I think that a major problem that I still see is that it has been challenging to have space to discuss political and strategic differences, right? Respectfully. Because at first we were kind of mostly on the same page, and there have been, we have not always agreed about strategy, about how we’re gonna do this stuff. And it is possible to fall into shit talk and to not be able to respectfully talk about political disagreements and strategic disagreements.

So much of our work started out where we had relationships. Either we were friends or lovers or we just have relationships and friendships. Some of us had like fights or conflicts or fallings out, but some of us just drifted. And then it becomes, what happens when the movement is bigger than your network of 200 people who are all your homies. And some of you have had fallings out. Some of you you just haven’t talked to for 10 years. How do you still have a movement that’s so relationship and trust based? And I don’t fully know the answer to that question, but that is a challenge.

Deana: I hear you. That’s a huge [01:03:00] challenge. Thank you for sharing that. With that in mind, with all these new people coming into the work, what do you want them to know? What do you wanna tell them?

Leah: Know there’s gonna be like ebbs and flows and ups and downs in the movement. There’s gonna be times where everything’s on fire and successful, and there’s gonna be times where you’re like, fuck, it is not feeling great right now. It’s feeling like we’re at each other’s throats.

Try and see the lesson in that, like one of my comrades at the height of the girl gang and also people coming for me moment, she was like, “okay, that’s fucked up and it’s hard, but like let’s dig deeper. Like what are the ways the movement isn’t serving people? That’s why this is happening. Like what are ways to address this?” And I was like, okay. And she’s like, “this happens in every movement. It happens in the sex worker movement, in the abolitionist movement. It’ll always happen.”

Last thing, and this is also advice, is like burnout. I had no personal life that was separate from the movement. I was doing this shit 24/7. And I in one way knew that it was the way I was holding my trauma from being a survivor, where I was like, [01:04:00] I’m gonna go make sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else, and that’s not wrong. But I really put a lot of my self-esteem and my value in whether I was loved and respected in movement. And so when there were times when it was like we just described, I got in a really bad place, and I think this comes up in a lot of movements. Like there’s a tendency to use yourself, like a tool or a weapon to be like, this is my value.

And for a lot of us, especially like racialized women and non-binary people and non cis men, that’s how we get praise is by always showing up and always doing the work. Especially in this movement where it was all confidentiality, very few structures, very few organizations. We didn’t get a sabbatical. It was like somebody else got raped, you could pick up the phone, bitch.

But I got to a point where I was like, I can’t see straight because of all these stories. Some of it was coming out of my role in my family of origin as like the caretaker, the helper, the smart one who will fix it. And it took me a long time to be like, I need to separate that out from what I’m doing.

I would never say no. And a [01:05:00] lot of our movement supported us in never saying no, you know? And just always being there. Oakland was really like ride or die. It was like, you don’t get sick, you just show up. You don’t be a flake. Like there’s a lot of post-STORM Maoist, like good cadre, vanguardism. That was also really ableist, that infected our work. That made it militant and disciplined, but also very harsh, right?

So my advice to people going into it is like, really keep thinking about why am I choosing to do this? And build in structures and moments where you can actually go on vacation and not pick up the phone at three in the morning. Or be like, I’m gonna take a year off, or I’m gonna be in the movement in some other way.

I don’t always have to be on the front lines, like, train your successors, have backups. Don’t work yourself until you get sicker than you already are. And know that the impact of hearing those stories is gonna have an impact even if you’re so good at disassociating, you don’t feel the impact for 10 years. Just know it’s gonna be waiting for you.

And like, that doesn’t mean don’t do it, but just like maybe it’s a healing fucking herbal bath. Maybe it’s something [01:06:00] else, but like, just really like, know that holding that vicarious trauma is not separate. Know that people are gonna come for you, and know that we need to figure out ways to respectfully disagree. But I don’t have the answer for that. But just maybe go into it knowing there’s gonna be disagreements, so you’re not always gonna be on the same page.

Mimi: One, I just have to say that I’m really pleased and heartened by some of the organizing that’s happening out there, that people are, I think in some ways, some people are coming with many more successes than I, I would have at the time, or that I am having at this moment.

And so I love that now I can go to other people and ask for advice. Some folks who are much, much younger than I am. Haven’t had the years, but have the wisdom. So thank you for that. Also, some of what we’re talking about is a way in which you have to see this as a long game. Have focus on a horizon that’s beyond any one of us. And that we [01:07:00] know that we’re gonna have backlash, we’re gonna have failures, we’re gonna fuck up, we’re gonna have people blame us, we’re gonna blame ourselves, and that we actually have to be persistent beyond all of that.

So that doesn’t mean not feeling bad. Of course, we’re gonna feel bad and doubt ourselves. I do think that I’m with a lot of people – I’m friends and colleagues in comrades with a lot of people who have that characteristic about them. So we can tumble through things. We can call each other or text each other when we’re really upset about something that went badly.

I mean, there’s so many different times when we could think everything we worked on totally failed. Constantly. Constantly. But what else can we do? We’ve gotta do this work, and we have to do it in a way, not that’s just killing us, but we have to do it in a way that, sometimes it’s really hard and sometimes isn’t fun. That’s just gonna be the truth of some of this. But that is [01:08:00] also in the long run that we seek our own sense of peace.

But also collective, and that, I think this is where we were saying – we, we had more opportunities to do that one time than we have to keep doing that now that we’re together with other people, that we talk about our frustrations. But that we understand, that we – then we pick up and we learn from that, and we keep going.

I think the plodding, and like I was saying, and then the plotting is also important. We have to be strategic. And we have to be better at that, and we can’t falter and feel like we’re gonna run away every time something goes wrong. I’m not saying that that’s what happens all the time now, but it does happen. And I, I see also a lot of people really anxious about failure.

We can all be a little bit kinder to ourselves to know that if we’re doing this right, it does, it means we’re gonna fail.

Rachel: I think, you know, just even drawing from where you left off, Mimi, I feel like one of the lessons for this work is [01:09:00] generosity. And I mean, you know, as I think both Leah and Mimi, you were describing generosity for yourself, but also generosity with others. Like we’re gonna mess a lot of stuff up. We’re trying to do things that most of us, I try not to speak in broad generalities like this, but I don’t think anybody actually knows how to do this really, really well or pep perfectly, because I think if they did, shit would be a lot different than it is right now, right?

So we need to be generous with each other. The idea of people coming for you or the idea of people like not being kind about stuff is, for the small number of us who get the most calls, I’m sure each of us has had to endure a whole lot of stuff of people being upset about the way things went, things we did or we did not do.

I am open to and probably deserving of all kinds of criticism. And it’s also like helpful when you’re generous when somebody’s trying to intervene on your behalf, right? And, you know, when you try it yourself, [01:10:00] you’ll understand that some of that generosity goes a really long way.

And then the other thing that I’ll say is, I think also related to a point you were making, Mimi, which is you have to practice, right? So you know, you can’t be afraid of perfectionism and you can’t be afraid of people giving you heat for doing the wrong thing. You have to try. And you have to try in a way that doesn’t make shit worse if you can. But also the more we practice, the more skillful we get. The more we practice, the more we learn. The more we practice, the more confident we are that we can actually do stuff. And you know, that kind of constricted brain that we get when we’re in crisis doesn’t give us zero options, but starts to think differently about the range of options that we might have. All of that to my mind, comes through practice, and we need to practice with each other, and we need to be generous in that practice of failing and trying again and failing and trying again.

We need to advocate for as much space [01:11:00] to fail and try again as possible because I think, you know, the stakes are high sometimes. I think sometimes if you’re trying to do things that abolish the punishment system or that try to address really, really heightened situations, the stakes are high. And, you know, the idea of failure doesn’t seem like it should be in the cards. But, you know, the practice helps us do better, and take better risks.

Deana: Thanks to our amazing guests. Although they no longer live in the San Francisco Bay area, we are so grateful for the role in movement they continue to play. We also wanna thank the organizers that currently live and work in the Bay Area, who are making this world a better place for all of us every single day.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories, Creative Interventions, and Just Practice Collaborative want to share new stories from people who [01:12:00] are taking action to end interpersonal violence. Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

Stories for Power is presented by Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative.

Executive produced by Mimi Kim, Shira Hassan and Rachel Caidor.

Produced by Emergence Media.

Audio editing and mixing by Joe Namy and ill Weaver.

Music composed by Scale Hands and L05 of Complex Movements in collaboration with Ahya Simone.

Stay tuned for more episodes of the Stories For Power Podcast. Check out our show notes and go to StoriesforPower.org to learn more. [01:12:45]