Deana: [00:00:00]

Welcome to Stories for Power. I’m Deana Lewis and I’m a member of Just Practice Collaborative. Stories For Power is an oral history project produced by Just Practice Collaborative and Creative Interventions. It explores the political lineage and historical experiments that gave way to this wave of transformative justice, community accountability and prison abolition.

In each episode of Stories for Power, we speak with activists and organizers from different cities who were and continue to be at the forefront of feminist abolitionist praxis. They talked about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the early 2000’s through 2010, and how their work informed abolitionist transformative justice and community accountability organizing today.

Don’t worry, if any terms or words have you confused. [00:01:00] We’ll do our best to link to resources in the show notes, and you can always go back to listen to the special introduction episode for more context.

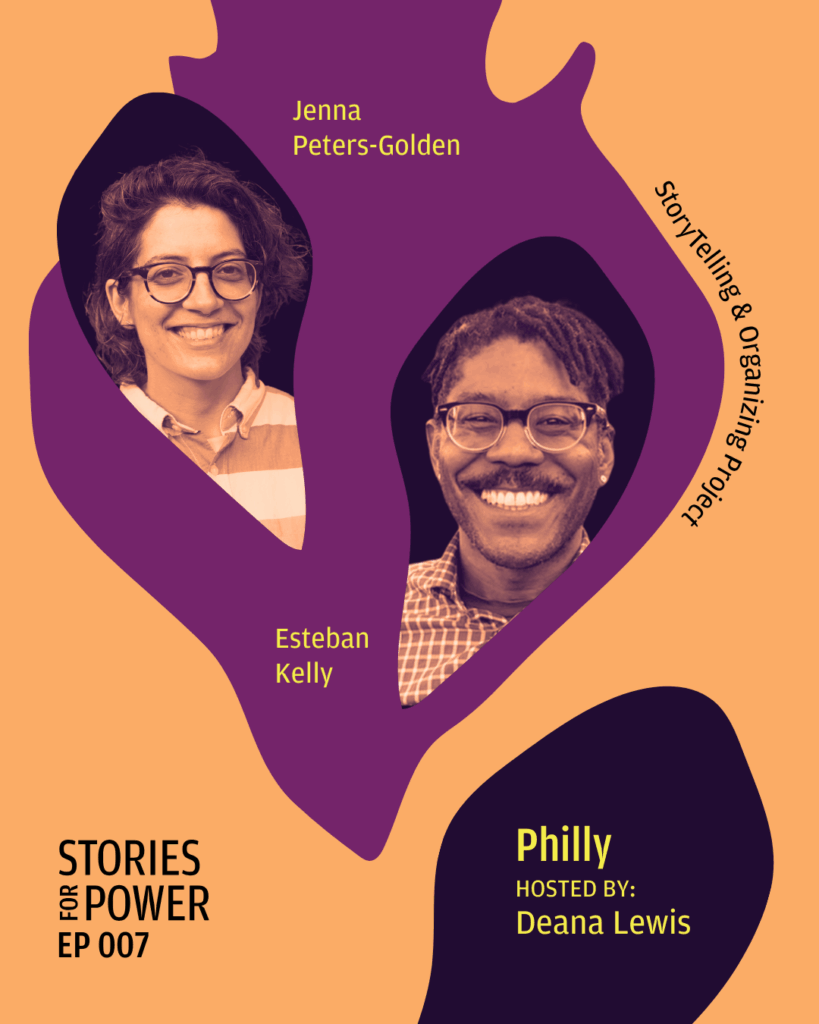

In this episode, you will hear from two amazing abolitionist feminists, Jenna Peters Golden and Esteban Kelly. We will talk about the courageous and radical work they were a part of in Philadelphia between 2004 and 2016.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions, and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems. Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

A note for our listeners, we will be discussing violence, including police violence, intimate partner violence, and community violence. We encourage you to take care of yourself and we understand that taking care of yourself can also look like not listening to this podcast [00:02:00] until you’re ready.

Now let me introduce our guests. They have amazing and extensive experiences and knowledge. I’ll do my best to summarize. We have linked their full bios in the show notes. You can also learn more on our website StoriesforPower.org.

Jenna is a white queer anti-zionist Jew who lives in Lenapehoking, also called Philadelphia. They’re a facilitator who works with many organizations and formations seeking collective liberation. When they aren’t facilitating, they might be drawing, working on kitchen projects, tromping in the woods, and playing with their kids.

Jenna: Hi, this is Jenna. I’m so glad to be with y’all. I joined the Philly Stands Up Collective in 2007 and was rolling with that collective until we kind of shifted gears in 2016. And that was the, the main project that I was a part of that had so many exciting threads to be in connection with other [00:03:00] types of regional and national transformative justice organizing.

Deana: Esteban Kelly is the Executive Director for the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives, founding President of the freelancer co-op, Gilded, and a worker, owner and co-founder of AORTA, a worker co-op that has built capacity for hundreds of social justice projects through intersectional training and consulting.

Since 2004, Esteban has been a member of the all volunteer Philly Stands Up Collective, which advances abolition through community accountability and transformative justice practices. Beyond that, he works to expand economic democracy through forms of multiracial solidarity and collective ownership.

Esteban: I am Esteban, and I was also a member of Philly Stands Up. I started pretty early on in 2004, maybe a couple months after the collective was founded. I think I was kind of the torch bearer, ’cause I hung in there, up through the emeritus status that [00:04:00] we’re in now. There were a couple different other movements or organizations that, as Jenna mentioned, that we were in cahoots or in collaboration with. And one is a cooperative that Jenna and I co-founded called AORTA. And through AORTA, which is an acronym, stands for Anti-Oppression Resource and Training Alliance, we did a lot of political education facilitation and, and… and training. Some train the trainers around the skills that relate to transformative justice and even the frameworks around abolition.

Deana: So what was the historical context for what was happening in Philly at the time Philly Stands Up and the other orgs got off the ground? Like I know Philly had a large punk scene and folks were doing a lot of political organizing.

Esteban: At the time that Philly Stands Up was getting started, culturally, there was still this lingering vibe from the ‘90’s punk scene, anarchist scene. Even politically there were not just the big summits where we were confronting corporate globalization, but, [00:05:00] but smaller ones – convergences around environmental justice and a, a lot of activism still around… around the MOVE organization in Philly, gentrification and, and dealing with the displacement.

Political cultures themselves were transitioning into the digital age. There was like the beginning of things like social media, much more in the MySpace era at this point. And even musically some of the really tight knit bonds around the subculture for punk or even for a lot of anarchist organizing that was itself beginning to transform in ways that we didn’t quite know the direction it was going in.

Jenna: Philadelphia was where the Republican National Convention was in 2000. New York City would host the RNC in 2004. And you know, they’re cities really close to each other and I think that also like pinged off things around collectives and formations around creative direct action that would feed into a lot of the conditions you’re talking about, Esteban, as well.

Esteban: Building on that, there was a lot of media justice organizing at the time. Part of how I ended up in [00:06:00] Philly in 2004 was that I came with a delegation that had borrowed equipment for the RNC in New York. So I was in New York and they were like, “Hey, we’re just gonna take a side trip down to Philly to return this equipment from the Prometheus Radio Project in Philly.”

In fact, I went, I, I went with Kane, who was one of the founders of Philly Stands Up and helped to recruit me into the collective when I moved here for real a couple months later. And we went and visited Cristy Road, she recruited me into Philly Stands Up.

Deana: Once you got into the work of Philly Stands Up, what were you responding to and what did you do?

Esteban: We had a really clear origin story. It’s really helpful that we started with that context about what the anarcho, punk, whatever community looked like at the time, uh, which was much whiter, middle class, and even straight than what our collectives ultimately became and, and what our movements became. But that is what we grew out of.

So there was a punk festival that was being hosted in Philly [00:07:00] in the summer of 2004, and there were, as part of that, multiple instances of sexual assault. For the people who were living here, yeah, they were pissed. And they also knew that they had agency, that they didn’t just need to let this go unaddressed and suffer in silence.

So they stayed organized. They had community meetings. It was very gendered. And at the time, a bunch of women in that punk scene, mostly white women, though not exclusively – I just mentioned our friend Cristy Road was, was part of this – decided to form a collective to address this called Philly’s Pissed.

It really was centered on not only supporting survivors, but really amplifying their agency. They really saw themselves as being not just a mouthpiece, but actually doing in the community, whatever, the survivors even coming from a place of, of harm and, and trauma and, and retribution or vengeance, whatever they [00:08:00] needed or whatever they wanted or whatever they sort of stated as their, their wishes to feel powerful again or to feel safe again.

And they said, we, we really need a companion group of men. And here they meant cis men and they were cis women. To hold people who had caused harm in sexual assault situations accountable. At the time, I don’t think it was really framed as a, this is what we’re trying to do in the community and the world writ large. It really was responding to a specific instance to say, “here are these particular or several men who were part of this community or part of the incident, um, and there needs to be a men’s group focusing on doing this.” So that’s where Philly Stands Up was founded. It took several months for those groups to start to collaborate more as peers and as equals in its initial conception.

It was really set up for Philly’s Pissed to be in the driver’s seat and to be kind of like bossing around Philly Stands Up, like, [00:09:00] here’s what you need to do and this is what accountability looks like, and here is this space within the community for people who weren’t maybe directly involved, to demonstrate that we have the capacity to behave in accountable ways.

Jenna: That specific origin story, the, the genderedness of it is a really critical setup because I think it’s a really important shape that led to, I think, really principled and important struggle and discomfort and kind of political inquiry a couple years down the road when I feel like I was more a part of the story.

Esteban: But there was a group called AMP, which stood for “against male privilege.” At the time, the framework really was around like not even using the language of male supremacy, but really male privilege, what we would now call “virtue signaling,” for men who wanted to sort of self-identify as being, what else would we say nowadays “woke” around gender, gender justice.

And I think that they, in good faith, were trying to develop their own analysis of male supremacy [00:10:00] and misogyny and how that played out in in particular ways, in their own lives and in their own communities at the same time that they were trying to understand larger structural things. People would show up to these huge meetings, you know, 30, 40, 50 cis dudes, and there wasn’t much substance. It really wasn’t much more than like some virtue signaling. Maybe they would have a workshop or something.

And the people who really cared about, there’s clearly an interest here, there’s clearly something that we could be doing, they kind of spun off and, and my sense is that they’re the ones who, who created this separate group that really, it was smaller and more intentional and it was called the Philly Dudes Collective.

And I think there the idea was what does it look like to have a small group of half a dozen men, and at that point, it wasn’t just cis men, which was I think, important and marks that shift in part…What does it look like to have a core organizing group and that we can then produce high quality intensive workshops or reading groups or whatever [00:11:00] around these sort of themes?

And it did end up being more effective, and had a larger role in, in the community and sort of open events and workshops that people could participate in. In October of 2004, there was a meeting for Philly Stands Up that had probably 20, 30, 40 people there. And in it, somebody who was kind of punk famous was called out by one of the other men at the meeting.

Not in a antagonistic way, but in a like, “hey, we need to take accountability for ourselves. Like if we’re part of this group, we need to be honest and candid. And there are women who have come forward and… and named this person as being problematic. So if we’re taking this work seriously, we’ll be back here next month and we’re gonna also address that situation of this person.”

And there was a lot of consternation in that meeting about whether or not to believe the survivors, whether or not to work on this situation. And what happened, in fact, was that in November of 2004, instead of there being 30 [00:12:00] people, there were two. So that was really the reboot of Philly Stands Up. It had cleared out all the people who weren’t really taking this seriously to heart. Like what does accountability really mean?

So they had two or three people, and the very next month when they were figuring out like, okay, we, this doesn’t mean the collective is ending. It just means we’re, we’re finally getting serious about what we’re doing. Let’s draft up our points of unity. We’ll use those as a template for recruiting anyone new who wants to join.

So in December, 2004, I was advised to participate. And I went, and it was probably, I don’t know, five or six of us at the time. Kind of overnight we queered the group. We, we made the group multiracial. We made the group multi-gender. And it stayed small, intentionally small and intimate from that moment forward.

The last thing I’ll say is that in those points of unity, it had the statement about, you know, who the group was for and what our attitude was. And so they said on a clipboard, like, here are our [00:13:00] points of unity. And it wasn’t, can you sign on the dotted line and agree to them? It was like, engage with these. Let us know if you have edits, ideas, feedback, and if we aren’t in alignment like wildly, then, then maybe this isn’t the group for you. But if the things you’re suggesting are things that we can actually wrestle with and incorporate as changes, like let’s do that.

Jenna: I first came into contact with Philly Stands Up in 2006 in Washington, DC at a now defunct conference called NCOR, the National Conference of Organized Resistance, and I was there with my comrades. We were a part of an organization called SDS, the new Students for a Democratic Society organizing against the war in Iraq, organizing against student debt, and stumbled into this workshop, um, about, I don’t know what it was called, but Esteban, Kane, I think, Timothy, were talking about what happens when intimate partner violence or sexual assault occurs inside our movements [00:14:00] and organizing spaces, and how Philly Stands Up was like working to address it.

It was myself and Beth and Zach who, whose names are important. I mean, we went to so many workshops at NCOR and like all we were talking about on the drive back from DC was, Philly Stands Up. And part of that was, I think, you know, inside SDS, that was our main organizing home at the time, sexual assault was happening all the time.

It was like this constant expected backdrop of everything. It just was really, really life-giving for us as, you know, we were 19 or 20. We’re really, really trying to like make big things happen. And we were like, you just can’t get through this part of the campaign. You can’t succeed in this action because, you know, people are sexually assaulting mostly like women and trans people all the fucking time.

And so Philly Stands Up was this, like, thing that really lit us up. And then in 2007, all three of us, me, Beth, and Zach, all moved to Philly when we finished college. I remember, we lived in a collective house at the time called Powerhouse and [00:15:00] received, I believe a handwritten love letter from Philly Stands Up, tucked into our busted up door.

Esteban: I tucked it in there myself.

Jenna: Did you? It was you. Oh, I’m so glad we’re figuring this out. It was an invitation to a potluck to come and see if we would be interested in joining Philly Stands Up. And we got on our bikes. We were so excited. We went to Food Not Bombs, to pick up all the free hummus we could, so we’d have something nice to bring.

I was really coming new to Philly, but coming with this fire in my belly where I was like, oh my god, there’s a thing that we could do that would mean that I could see what liberation and justice looked like. I could see what felt like sexual assault was doing to our movements, which all these amazing unrealized ideas and possibilities around justice, like twisted up and like thrown into this like huge junk pile.

The way it would sort of work is that a person who experienced sexual assault [00:16:00] or intimate partner violence would reach out to Philly’s Pissed and meet up with someone from Philly’s Pissed. Basically, Philly’s Pissed contact us, would call us, would email us and say,”hey, Philly Stands Up, we have a situation.” And the idea was that Philly’s Pissed was working with the survivor and that Philly Stands Up would be working with the person who caused harm. And that there would be points of contact from each collective who were meeting with each other. So like a team from Philly Stands Up and a team from Philly’s Pissed. I think we were all pretty good at always working in teams. No one was working on situations alone.

Esteban: Except in the worst circumstances where things went off the rail.

Jenna: That’s true. And it always was the worst. I think when I joined in 2007, we were really experiencing some growing pains where it was feeling like, Esteban, as you said in the early days, it was really like Philly Stands Up, was designed to be kind of like in service of Philly’s Pissed needs and mission.

And I think we started really feeling the edges of that in like 2007 and 2008, in part [00:17:00] because I think Philly Stands Up was coming into both political study and praxis and also just experience, where it’s like sometimes the exact thing that the survivor wants, it doesn’t actually lead to end goals of like transformed behavior, making sure that this person maybe doesn’t like commit harm again.

And we were sort of starting to, I think as a collective, come with some questions and pushback and edge and wonderings with Philly’s Pissed. Also, at that time, you know, by the time it was 2007, we were, like, almost entirely queer women, trans and gender queer people.

Esteban: So I think the other important thing to describe about our organizing structure was layers and layers and layers and layers of confidentiality and code, names and secrecy. There was a way that we could be advising a situation without having any idea who was involved. It could be your coworker, it could be your boss. It could be [00:18:00] your ex. You might you, you often wouldn’t even know, or you might not find out until years later, or until like some bigger crisis came in and someone was coming to the group and saying, “look, I, I need to actually tell you a little more about who this person is because there’s risk to the community, or something like that.”

But it was really helpful because it meant that we didn’t have to think about someone in particular. We were able to just, like, think about the abstract person and offer advice or empathy or strategy without any of the baggage of who it was. Like not knowing their age, not knowing their race, usually, sometimes we did. We often did know their gender expression or identity and maybe a little bit about how they were embedded in the community.

You know, is this someone who drinks? Is this someone who goes to shows a lot? Is this someone who’s more in activist spaces? Like we would have a sense of those sort of things. It also added to the resilience of both of the collectives that we did not know who all the people were. And as certain individuals [00:19:00] had more and more access to the identities of who was involved in the situations, it was like always just a matter of time before they were like, “oh, this is too intense. Now I’m burnt out. Now I’m not doing this anymore.”

Like, so the structure was each collective had a liaison and they would meet usually about once a week or every two weeks, and they just had a menu of all the different code names. And sometimes the code name would start with us or it would start with Philly’s Pissed, or sometimes we would have different code names for the same situation. But they would compare notes and get updates and share like, here’s the progress we’re making. Here’s who’s working on this, here’s what isn’t making progress ’cause we can’t get things scheduled, or they’re not responding, or they’re not being accountable or whatever. You know, here’s an updated set of demands or requests or an updated timeline about those. And so our point person wouldn’t know, necessarily, who was involved.

They would just show up and be like, okay, “we’re gonna talk about Pizza, then we’re gonna talk about Newsies, then we’re gonna talk about Bio Dev Perp Number One” or whatever the different things were, compare those notes and then they would go back to the collectives and [00:20:00] share those report backs or updates at that level of anonymity.

And so often the people working on the situation didn’t know. Like, if I was working on a situation, I didn’t know who from Philly’s Pissed was working with the survivor for that situation necessarily. And it did make it a little easier to create a lot of space for creative thinking, for empathy.

Deana: Absolutely. That space is so necessary in TJ work. So at this point I usually ask for success stories and challenges in separate questions, but I wanna point out for folks that you, Jenna, you co-wrote an amazing article and the title is “How We Learned Not to Succeed in Transformative Justice.” And it complicates ideas of success in this work. So I’m not gonna pretend the concepts are separate from each other.

Can you both share more about experiences and challenges you had as community accountability facilitators?

Jenna: It could be really seductive for facilitators to be like, “look at the things I’ve accomplished and how great our processes are.”

So I think that [00:21:00] balancing the structures of the carceral system on our imaginations, the critique around rape apology, and then also, um, seeking compass points in a really confusing, overwhelming, sometimes very like, you know, long periods of time that can feel kind of unfulfilling, where you’re like, “oh my God, I’m so tired. I’m working so hard. Like, is this worth it?”

So I think that we, we also really were like, we don’t wanna get stuck into like a nonprofity, like “look at all of our milestones that we’ve done.” And wanting to be like, how can we be rigorous? Critiquing ourselves, like giving each other and ourselves feedback, which sometimes means not looking for, like, what was a failure and what was a success.

Esteban: We didn’t really name the ways in which this was like an all volunteer collective. We met weekly on Sundays. We would take intentional breaks and hiatuses often over summer, ’cause it was like, people are traveling or doing other things. But sometimes just like when mental health stuff was going off the rails, we were like, “hey, attendance has been low for three weeks in a row. Do we actually need to just, like, take a break for, for a [00:22:00] little while?” That cadence of meeting like every Sunday night. And sometimes individuals would step back or go on a leave or a hiatus, but often we would just continue the collective as a whole meeting for a decade plus was, I think a big part of it.

That no one was collecting a salary, that there were no grants or deliverables, that these were things that could very easily be funded if any of us wanted to push things in that direction. But it was against our points of unity. It was just, like, not the point of the work. And there’s something about not being sucked up into the disciplining behaviors of the nonprofit industrial complex that fed our resilience and our persistence, our endurance for doing this work.

Yeah, the other thing I was gonna say about successes, and maybe this builds on what you were just speaking to, Jenna, was in some ways the banality of it. Like, it’s really funny thinking about this question. I’m like, huh, there aren’t that many things that jump out or that stick with me as remarkable, and I’m like, ooh, maybe that in and of itself is a success. The idea that there’s [00:23:00] very few things that stand out like that there’s a lot of situations that moved along where we engaged, where we, we iterated, we learned little lessons along the way. We developed our own sort of praxis and analysis around transformative justice along the way.

Jenna: We really started incorporating political study into our meetings. We were reading books, we were reading articles. Like that started to become not the central thing we were doing. That really clicked a different moment for Philly Stands Up.

And then I think that that also pushed us into being in community and network with so many other amazing projects and organizations. Some I’m sure are featured in this awesome podcast series. It allowed us to develop some really great boundaries, to get more specific and precise around like what’s the work we’re doing here? Right?

It’s not that a person who perpetrated harm’s trauma gets to take up more space than the survivor that’s calling this process together, but like we get to be a little bit nuanced here.

And I think I started to do much better work with people who are perpetrating harm. Like actually started to facilitate [00:24:00] community accountability projects much better the more I was learning about trauma and the kind of connections and generational lineages around sexual violence and as like a non-cis dude who was working with like the vast majority of cis dudes.

Deana: I appreciate you for bringing up that nuance and naming the importance of understanding and studying trauma as we do this work.

Now, without contradicting the last question, we do wanna hear some stories of times the work went well. Do you have examples to share?

Esteban: One was instead of having situations referred to us because of a survivor present in our community, we started getting emails from people who had caused harm who just sought us out.

It’s like years have elapsed and I am coming forward. I, I know that there’s stuff I wanna work on. And it’s different than therapy, right? It is, it is a thing of like, I actually am trying to get in right relationship. And I have an [00:25:00] understanding of what went down. And, and what are my patterns and behaviors? And how do I show up differently?

I consider that to be a success, like every one of those moments where someone came to us and the ways in which it pushed us to approach the work differently. And even what that demonstrates. I mean, it’s very much like the opposite of cancel culture – the fact that people would voluntarily seek us out and step up and make themselves vulnerable.

Um, and in some instances, we would coach them in, they’d be like, “Hey, I wanna reach back out to the people who I think I’ve harmed. Do you think that’s okay?” And so we would, we would think through that. And sometimes it would take months and months we’d be like. If you haven’t heard from them, they might be just healing. They might just want space. They might not want to hear from you. So just what it meant to accompany people along that journey and to try to figure out how to reengage, um, in an appropriate way, I think is one aspect of success.

Jenna: One situation that, yeah, our comrade Bench and I co held for this process, that was just a challenge for a long time. There, there were many challenges inside of it, all of which we grew [00:26:00] from. The first thing we came against is the person who perpetrated harm. There were a lot of hopes on what they would land on. A lot of like tangible, specific asks around private and public letters of apology. Ways of demonstrating their accountability. There were guideposts around what was okay for their dating. Like we’re saying, please don’t date or, like, sleep with anyone until you’ve done X, Y, Z. And also, people in the broader community were exercising the anger and rage that they felt by making sure, like, everybody knew about what this person had done.

And so what that meant was that by the time this person was sitting down with Bench and I in a coffee shop, they hadn’t been able to hold down a job. Everyone was telling their bosses wherever they were, that they were a sexual assaulter. They didn’t have a reliable place to live. Their mental health was really struggling, and we were just like, fuck.

And they were feeling the pressure. They were like, I’m so lonely. I’m so isolated. I [00:27:00] can’t date. I’m not allowed to do these things. You know, the way that the things were structured and the way that they were experiencing things was all in context of can’t. I’m not allowed to do this, this, this, this, this. I don’t have any money. I don’t have a place to crash. You know, all of these things.

We really felt the challenge of that. And I think a thing that felt politically confusing for us, where we were really like, well, politically we support survivors, you know, getting to ask for what they need. And there’s no way this person is gonna succeed in that ultimate success, much less any kinda meaningful transformation. It was leading to them feeling really victimized. It was making not only their life harder, but the facilitation of this process, like very, very challenging.

And so, you know, we ended up calling on a lot of support from other collective members and pushing pause on the process and being like, we need a couple months to just figure out housing, job, and like a therapist for you.

And we were able to figure that out and then breathe for a minute and then come back in and start the process. But it really felt like we had a couple different starts of that process and it, it led us to just really experiencing the kind of material conditions that needed to be [00:28:00] available for any kind of level of success, much less personal and community transformation to be possible.

And I think the last thing that I’ll say that I think that any of us who have done community accountability work know, our survivors know, and have worked to be accountable ourselves for things, is that the challenge of being like, community accountability processes oftentimes don’t feel good to survivors.

Whether they’re a part of somebody or a community’s healing process or not, it doesn’t usually feel like “I’m healing.” Um, isn’t usually like a part of what it feels like to actually be in that process. You know, as practitioners, we were really around the process and I think that I experienced so often being like, how do we complete these goals or fulfill our niche in this ecosystem, knowing that a lot of times the healing isn’t really coming from us. Like we’re not the ones who are making folks feel good, people who perpetrate harm or survivors.

And that was painful, especially ’cause yeah, we were a collective of survivors and people who really believed in the work. As add a challenge there. It also made us really lean into this bigger ecosystem that we were a part of.

I remember attending a [00:29:00] workshop at AMC, I think by YWEP, was healing for so many of us who were there, like, being, being able to be connected and fed and inspired by folks who are a part of this ecosystem, but doing different pockets of work. Allowed us to be like, this is a part of a tide, a tide of change and liberation that envisions healing.

I, I think of Philly Stands Up as successful purely because those of us who closed out the collective in 2016 are all fucking in love with each other still. We got a shout out, Dexter Rose, Qui Alexander, Beth Blum and Bench Ansfield, and like so many folks who’ve been in the collective who aren’t getting interviewed right now, who are such brilliant organizers and practitioners and thinkers and risk takers. And so I think that like that relationship and connection really kept us going through the, like, this shit doesn’t feel good, but damn, Sunday night meetings feel so good at your house, Dexter.

From a different situation, this was doing a, an accountability process with someone and it was tough. We unlocked in that process like a lot of vulnerability and connection and compassion. And the perpetrator [00:30:00] was able to kind of meet all the goals that were set, which involved heartfelt apology, an intention to change their relationship to substance use, some stuff around money that the survivor needed to be more well in their body and you know. So we kind of like closed it out, and we were like, “bye. It was like good being in the work with you.”

And then this person moved outta town and then a couple years later I was at a bar and I ran into this person. You know, I was kind of doing that thing where I was like, gave a little hi, but like maybe you don’t wanna. I don’t know. It’s like what my therapist does when they see me in the world. Um, and he just like charged over to me. And was like, “oh my god, Jenna”, like, this was the only time it ever happened to me and like was like, “you totally changed my life. I know I’m at a bar right now, but like I’m sober. I don’t drink. This is my new girlfriend.” He’s very sweet. But you know, I really just got this, like, kind of five minute bath of the ways that he had metabolized the lessons and how that had changed not just like his life, but also his capacity for resilience around receiving feedback. And it was really sweet and really cool, and not [00:31:00] a thing I’ve experienced that much of.

Deana: Wow, that’s powerful. It’s so important to hear, especially for new folks who are coming into this work. What else would you want new organizers to know?

Esteban: We were able to be successful because we were able to be unsuccessful and to fail, and it wasn’t public and hashtagged and all over social media and dragged and reputational stakes and all of that.

Like things happened in person. They happened locally when we fucked up and we fucked up a lot. There were bridges burned, there were people who were hella mad. There are people who still don’t talk to me, or some of the people who are working on situations. And, they were contained fires. And so just keeping that context in mind, I think it’s really important to think about, like, what are the structures we are creating to practice transformative justice, to test out community accountability processes, that can be a little bit [00:32:00] firewalled – where it’s safe to make mistakes and to fumble, and it’s not apocalyptic.

Keep that in mind in designing whatever it is you’re gonna do. And also in not becoming the mob. That’s, I mean, that’s really what, what people need to know nowadays. It’s so easy. We’re so well trained to pile on and to be like, “you’re doing this wrong, and that’s not the principle and that’s not abolitionist enough and this is…” But just actually tossing all that out and not being so precious.

If we believe in abolition, that means working with everyday people who are heterodox as fuck. They’re not ideologically pure and aligned and similar in any way, shape or form. And that’s not what matters. What matters is the relationship is being with them and moving things along. And so that means there’s gonna be people who like, yeah, they might mess up your pronouns, or they might be like, whatever the thing is.

Like to actually be like, all right, working with every day, especially poor and working class people. We need to increase our ability, our cultural tolerance for, for people who like vibe in a different way. [00:33:00]

Also, practice is everything. Like the other reason we were able to have successes, failures, and all the middle stuff in between that, like I was saying, is the stuff that really mattered is that we just kept doing it.

We met every single week, every single Sunday. Together every single Sunday. If I was working on a situation with Jenna, we would have a separate meeting on a Tuesday or a Wednesday or something else. Right? And then we would meet with the person on a Friday or a Saturday, and just like having that surface area.

I think nowadays, and in some ways it’s like there’s positives to this, but there’s, we’re so immersed in the, the frameworks and the, the diagrams and the resources and the, it’s books and podcasts and workshops and there’s, there’s no shortage of materials. But that really needs to recede into the background and be reference.

Start by getting your hands in there, working on situations. Even if you’re not working on high stakes, like survivor support things, just like [00:34:00] do mediation, do conflict resolution, do deescalatory things. Any amount of that is gonna give you some important exposure and practice in what it looks like to just be with people in their communication issues, seeing how ego shows up, how their identities might show up, how some of their wounds and trauma might show up with something as basic as service provision.

We were talking earlier about Food Not Bombs, like, interacting with everyday people and seeing like, “oh, what are the different ways that people show up and what else might be going on there?” So much of what you learn is by doing, and that has been undermined over the last generation really. I think there was a, a stronger respect for that in like 20th century organizing, and it’s starting to erode with all of the listicles and all the like Instagram, you know, posts, and whatever. To actually just like close your computer, put your phone away, and just sit down with people in tricky situations and do your [00:35:00] best and receive feedback about how you did. And, and if you can build community along the way. If you can be with, you know, three other people or two other people and offer each other notes and feedback, that’s the real business.

That’s how you’re gonna learn.

Jenna: Something that’s different now is the way that, the feeling that I, I think a lot of people who are a part of community projects or organizers are in meetings all the time. You can click from one meeting to the next meeting. You can call in on your way to another meeting. You can call into this meeting. You can just be in meetings all the time. And doing work around transformative justice, community accountability, and really like wear at your heart and your spirit. I don’t think Philly Stands Up would’ve been… yeah, I I don’t think I can emphasize enough the way that we, like, loved each other and we built sacred community with one another.

You know? I mean, I think, I think the advice is like, this isn’t transactional work. This isn’t like you get the people, you hop on the Zoom, you, like, run through the agenda and you’re done. This is like heart work. This is some [00:36:00] sacred work and that’s how I relate to it, right? Everyone can have different ways that roles for them, but imbue whatever you’re doing, whatever shape you’re taking with like love and time and care and culture.

If you don’t have something to hang on that, especially work that’s as fucking hard and can be as painful as this, I wouldn’t wanna go to that meeting, no offense, but…

Deana: Thanks to the amazing organizers that live and work in Philly who are making this world a better place for all of us every single day.

As always, I encourage you to take the lessons you learned today and keep practicing.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions, and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems. Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

Stories for Power is presented by Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative. [00:37:00] Executive produced by Mimi Kim, Shira Hassan, and Rachel Caidor. Produced by Emergence Media. Audio editing and mixing by Joe Namy and iLL Weaver. Music composed by Scale Hands and L05 of Complex Movements in collaboration with Ahya Simone.

Stay tuned for more episodes of the Stories For Power Podcast. Check out our show notes and go to StoriesforPower.org to learn more.