[00:00:00]

Deana: Welcome to Stories for Power. I’m Deana Lewis and I’m a member of Just Practice Collaborative.

Stories For Power is an oral history project produced by Just Practice Collaborative and Creative Interventions. It explores the political lineage and historical experiments that gave way to this wave of transformative justice, community accountability, and prison abolition.

In each episode of Stories for Power, we speak with activists and organizers from different cities who were and continue to be at the forefront of feminist abolitionist praxis. They talked about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the early 2000s through 2010, and how their work informed abolitionist, transformative justice, and community accountability organizing today.

Don’t worry, if any terms or [00:01:00] words have you confused, we will do our best to link to resources in the show notes, and you can always go back to listen to the special introduction episode for more context.

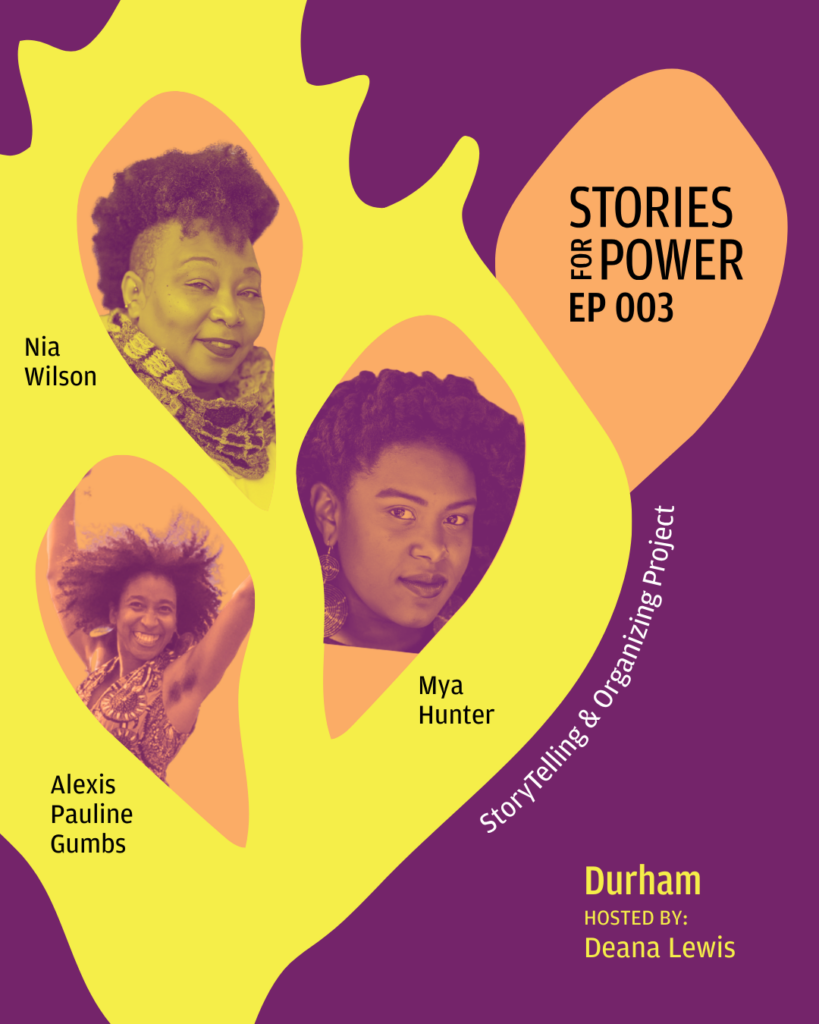

In this episode, you will hear from three awesome abolitionist feminists, Nia Wilson, Mya Hunter, and Alexis Pauline Gumbs.

We will talk about the courageous and radical work they were a part of in North Carolina between the early 2000s and 2010. Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories, Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems.

A note for our listeners, we will be discussing violence, including police violence, intimate partner violence, and community violence. We encourage you to take care of yourself and we understand that taking care of yourself can [00:02:00] also look like not listening to this podcast until you’re ready.

Now let me introduce our guests. They have amazing and extensive experiences and knowledge. I’ll do my best to summarize, we’ve linked their full bios in the show notes. You can also learn more on our website StoriesforPower.org.

Nia Wilson, also known as Mama Nia, is the daughter of Ronald and Elmira, and the mother of Heather and Paul. Raised on Connecticut concrete and sand, Black Soul and Campbell’s pork and beans, Nia is a gifted healer, story weaver and cultural alchemist, as well as the co-author and producer of SpiritHouse Inc’s original production “Collective Sun Reshaped the Mourning.” SpiritHouse is a multi-generational Black women led cultural organizing tribe with a rich legacy of using art, culture, and media to support the empowerment and transformation of communities most impacted by racism, [00:03:00] poverty, gender inequity, criminalization, and incarceration.

Nia, can you talk about what kicked off your work in general? And also to give context to our listeners, I would love to hear more about how your community responded after a Black woman who was a stripper, dancer, and sex worker accused the Duke University lacrosse team of sexual assault in 2005.

Nia: I’m Nia Wilson, and I’m a part of SpiritHouse. In the early 2000s, SpiritHouse was doing a program called “Choosing Sides: Life or Death in the Black Community.” It was a youth program where we were working with students who had been suspended or expelled from public school. Many of them were part of different street organizations, and so our work was to try to get them to understand that they could work together and that they needed to choose life for themselves and their community by learning [00:04:00] to be together.

There was a point in 2005 when Durham was going through a very difficult time, and there was a large international spotlight on Durham. And many of us were, are Black women and survivors, and we formed a beautiful, lovely group called Ubuntu, which was being led by Black and brown survivors. And we were able to be together through that moment as well as doing a lot of community work and organizing around what it would mean to create a world where there was no sexual violence.

And in Ubuntu space is actually where I first became acquainted with abolition and got a much deeper understanding of [00:05:00] what it means and how to begin to practice abolition. .

Deana: Born under the Aquarius Sun sign, Mya Hunter is a fourth generation Durhamite. She’s also a daughter, sister, friend, performance artist and documentarian. She has a deep sense of love and duty to her hometown. Starting as an afterschool program participant, she moved into SpiritHouse’s intergenerational co-directorship, bringing a clear vision and direction to SpiritHouse’s work.

Mya: So I’m Mya, and around that timeframe, 2000, 2010, I was actually a high school student. Well, not that entire time, that’s a long time to be in high school. By the time I came on the scene, at that point I had been co-founding a youth group called Youth Noise Network, and we did audio documentary work majority of that time. I was about 13 when I co-founded. I [00:06:00] was, I wanna say a sophomore, junior, when my program was up for the chopping block.

And at the time we had some SpiritHouse, young people from Choosing Sides and SpiritHouse, in general, in our program. And so the option came up, where would you take on Youth Noise Network and SpiritHouse said “yes.” So we became essentially the media arm of Choosing Sides. So our lightly political commentary at that point became very political.

And so our documentaries about slice of life, almost, commentary about school and around sexism and things of that nature to more intimate, harder topics around, what does it mean when some of us are dealing with the effects of gentrification? What happens when we’re having conversations about our relationships to police and policing? And that wildly shifted the course of a lot for me. [00:07:00]

Deana: Alexis Pauline Gumbs is the author of several books, including Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals; Dub: Finding Ceremony; M Archive: After the End of the World; and Spill: Scenes of Black Feminist Fugitivity. Alexis and her partner Sangodare are co-founders of Mobile Homecoming, an experiential archive of generations of Black LGBTQ Brilliance.

Alexis loves and is loved by her community in Durham, North Carolina, where she’s part of the SpiritHouse tribe and egbe, and working every day on her dream of being your favorite cousin.

Alexis: I’m Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and I moved to Durham in the early 2000s to go to grad school and one day, it’s a longer story, but while… while crossing the street, I was invited to join SpiritHouse and support [00:08:00] with the youth programs, including Choosing Sides, which Mama Nia mentioned, and YNN, which Mya just mentioned. And when the Duke lacrosse rape case really became this huge traumatizing, and definitely, for me as a survivor, retraumatizing, and also as someone who lived directly around the corner, it was something that really shifted how I thought about why I was involved in collective organizing.

I realized that I had never thought about being a survivor as a political identity or as anything that I would wanna think of as an area of leadership or expertise or that it had any value actually at all. And this was a situation where I had to think about that differently and there’s no way that I could have even transformed my relationship to that alone.

[00:09:00] So SpiritHouse became part of the coalition, Ubuntu, and Ubuntu operated in coalition to create the National Day of Truthtelling, which was a survivor led direct action where we marched through the streets of Durham, really reclaiming them with the energy of our survival. And in Ubuntu, I was blessed to, along with Ebony Noelle Golden, we served as the first co-chairs of the artistic response part of Ubuntu, which was really about how art and creativity can be a space where we transform our ideas.

And really make ceremony for the possibility of a world without sexual violence.

Nia: Ubuntu is what led us to kai, who trusted us with the stewardship of the Harm-Free Zone, so I think that that’s important. And again, it was kai who brought the idea [00:10:00] of prison abolition to the Ubuntu Coalition, and we did a lot of work around that in Ubuntu.

So this major horrific incident happened in Durham, and I don’t remember exactly who put out the call, but there was a call for survivors and organizers to meet in kai and shirlette’s living room in Durham. The question was, what was our response gonna be? So there was an initial direct action on the lawn of the house.

There were pots banging and there was a toilet. Nikki Brown, one of our members, talks about it because that’s where we met. There was an action with sort of a artistic kind of response where we actually were wrapping this toilet in paper, and that was the initial response. The media was here from all over the country, [00:11:00] and I worked across the street and saw Duke students all the time.

So we realized as we were meeting that it was more than just the political response to the moment, but that we also had to create a practice of care for ourselves and for each other. We broke into different communities around artistic response, around education, around governance, around care. We had a lot of dinners and poker and all kinds of things that helped us to love up on each other.

We cried a lot, and we responded through things like what Alexis was saying around The Day of Truthtelling. Our lives were being threatened, literally being threatened at the time, and so we also had to think about what it meant to protect ourselves and each other. And that was, again, is where the, without the use of police, came in, sort of, to being we couldn’t call the police.

You know, I remember the [00:12:00] conversation where kai said, you know, we have to think about what we want to happen to these young men because we don’t want to put them in cages. And many of us were like, what are you talking about? You know, what do you mean? For multiple reasons, but also, again, remembering that we are survivors.

And so to have a conversation with someone who has survived their own trauma and to say, but we’re not gonna use the police, was pretty foreign to us. But we all, we stayed in the room and we listened. Some of us shifted pretty quickly, and some of us, it took time to come to an understanding around why the use of the, the, punitive carceral system will not save us. So, you know, I would, I would say that for Durham, at least, that is where the movement towards abolition, towards accountability and [00:13:00] transformative justice took root. I’m not gonna say that it wasn’t here before then, but I would say that this is where it took root.

Alexis: I also wanna name some of the mentors who, and these like Black women visionaries, two people who I’m gonna name, who are now ancestors, who were, who were mentoring and shepherding also the whole time. Mama Nayo, Barbara Malcolm Watkins, and Cynthia Brown [1] were people who were, I mean, I think I’m speaking for all of us, but I’ll definitely speak for myself. They were definitely bridge people who were connecting us to long, long, long through line of women’s leadership of movement, brilliance, of a really loving approach to what our revolution could be.

Deana: That’s beautiful. Lineage and [00:14:00] mentorship are everything. So you just talked about the response to the Duke lacrosse rape case as an important historical moment for SpiritHouse and Ubuntu.

Were there other historical contexts in the city or surrounding areas for your communities that you were also responding to?

Alexis: Yeah, I, I would add Durham already had like a 10 year master plan also going on at the same time that involved displacing people of color. It was basically the gentrification plan, and I didn’t know about that plan at the time, but that was happening at the same time, which was also contributing to the tension.

Mya: All of my memories are my teenage memories, right? So that moment in time was, I remember how tense the school situation was, and there was a lot of concern about how violent Durham gangs were at the time. There was a “documentary,” I’m making air quotes, called Welcome to Durham, [00:15:00] that really set the stage for people’s understanding of Durham and the violence that was happening here.

And it was also the backdrop of like, we were preparing for the recession. And so the predatory lending bubble, the Wall Street conversation, all of that was about to like bubble burst. So everything felt incredibly tense at that time.

Nia: We were already working around like school suspension and policing, dealing with a lot of young people who had been arrested for one thing or another, facing jail or probation. So we were also doing a lot of work around education and around the disparities in school discipline, school suspension, and the school to prison pipeline.

Alexis: I would add that at the time the Durham School Board was openly hostile to the children of [00:16:00] Durham.

And I remember when I first moved to Durham seeing like people’s grandmothers being restrained by the police for trying to speak out at the school board meetings. So I’ll say that too because I think that our local government continues to be complicated, but there’s been a lot of shifts since that time.

And I think that also was a moment where people started to think like maybe there are different ways to get involved. Maybe there are different ways to really honor the youth of the city. And I will also say, because it is a historic event, that kai lumumba barrow moved to Durham. That that’s a very big deal.

Even like Ubuntu started in kai and shirlette ammons living room, and kai’s connection to Critical Resistance really is how we all got connected to Critical Resistance. To me, it wouldn’t make sense to tell this story without kai.

Nia: She was absolutely pivotal [00:17:00] in what was happening on the ground in Durham and absolutely with SpiritHouse and the Harm-Free Zone work.

Mya: And kai is a character and that’s important for, because she’s this little, there’s no explanation for the amount of energy that kai’s body somehow is able to contain and then this hair. And so I just remember one of the first conversations. And I’m sure this wasn’t the first, but it’s the one that stuck was a conversation around, if someone steals an apple out of your yard, what do you do?

Are you gonna call the police? Well, does that person own the apple? The apple was probably there before the person was there, and it was just like this pivotal conversation lesson for me that I was like, oh yeah, I’m a country girl. Like, yeah, people take apples off trees all the time and no one’s concerned.

And somehow the conversation about taking the apple off the tree then was like, we need to address the cop in our heads. I just remember [00:18:00] thinking, a cop in my head? I don’t have a cop in my head. And then she was like, no, no, we all have cops in our heads.That was the lead off sendoff conversation going to CR 10.

Alexis: I think we all became involved in Critical Resistance, and I know I was on the planning committee for Critical Resistance 10, and then Choosing Sides and YNN came to Critical Resistance 10, and so that was actually very formative in how all of us moved from that point on.

Nia: You know, we did some fundraising for folks to go to CR 10.

We took our young people to CR 10. It was transformative for many of us.

Mya: That was my first big trip across the country. This was a space where people were talking about, what would the world look like if there were no prisons. Communities were taking care of each other, free tamales in the park. Like for my little teenage brain it was like a euphoric moment of just like, wow, this is what community can look like. [00:19:00] While also having hard conversations around not throwing people away, like it’s not an option. We can’t throw anyone away, and just to prove that we’re not throwing anyone away. Here are the letters from our loved ones behind the wall, and it was just this deep sense of love and community that I hadn’t seen up until that point.

Beyond living rooms, like we were in living rooms, we were having these conversations and while I was in some of those conversations, I’m 17 so people are like, interested in hearing what I have to say, but also I’m like deeply in, we don’t speak unless spoken to mode. So I’m like, I’m here to listen. And I just remember being constantly encouraged that I had a story that was valuable and needed to be in the room and in the space.

And it shifted radically how we moved from that point on. At that point, we were also performing. Asha Bandele’s The Subt… Subtle Art of Breathing, which was a series of memoirs and vignettes about her relationship with her [00:20:00] love who was behind the wall. And I remember having conversations about how we all had stories about someone who was incarcerated, who had been harmed, who was justice involved.

At the time I was also dealing with my own relationships to prisons and policing. At that point, my father was in and out of jail consistently and constantly before getting deported. And this pocket that Ubuntu and SpiritHouse had created for young people to have this conversation. It was pivotal ’cause I don’t know anybody else who was having that kind of conversation.

So we were also meeting other young people who were justice involved, having these conversations about their times with juvenile detention centers, talking to folks who lived in the Appalachian Mountains about what does it mean when a prison tries to build in your backyard, the complex relationship around people needing work, and also what does it mean to be complicit in prison industrial complex. Right? [00:21:00]

I just remember at this point in time, there was a lot of desire to have the conversation and not a lot of words for how to do it. So we were trying to essentially build language around community care and some of the things that we now like a lot of co-opted terminology around like community control and community care and all these other things.

But at the time we were really struggling to find language around things that at one point it was, it was not a question. At one point, our communities didn’t have the option of calling the police, and this was still a moment where we didn’t have the option to call the police. But we had gotten used to the idea that if something goes wrong, you need to pick up the phone.

And so we were having these courageous moments of being like, so if I don’t call the police, then who do I call?

Deana: You’ve mentioned this already, but I wanna go back a little bit and ask specifically about the Harm-Free Zone. And Ubuntu, can you tell us a [00:22:00] little more about them?

Alexis: Ubuntu is a women of color survivor led coalition to end gendered violence and create sustaining transformative love.

In my opinion, that’s the name of Ubuntu. I don’t think anybody else says all that except for me. But I remember us having a visioning where we used each of those words. It existed in its particular form, as you know, leading up to The Day of Truthtelling and as a space to really respond to what was going on.

But it also, I think, has informed so much that continues to happen. I mean, including the Harm-Free Zone, but also different iterations of abolition, especially that exist in, in Durham right now. And the fact that it is women of color who really are at the center of creating and sustaining that.

And then I would also say, I will, I don’t think I would’ve thought of it this way at the time, but I do think that like the response to the lacrosse [00:23:00] case, the creation of Ubuntu and the Harm-Free Zone, and I, I think this is actually how SpiritHouse transformed from an organization that had a view of revolution that was very influenced by Black cultural nationalist forms, patriarchal instantiations of, of Black arts movement, to really being an abolitionist feminist organization. It’s not necessarily something that was on the website or anything, you know, during, during that time.

But that was, that was a shift. And for me, I experienced SpiritHouse becoming an organization that could have a survivor centered and led vision of revolution, at that time.

Nia: We had a meeting with some of the folks who had gone to CR 10 to make some decisions around, okay, well what are we gonna do now? What are we, how do we continue to move? And there were some suggestions around joining certain campaigns. [00:24:00] kai said, we can support campaigns, but what are we really trying to do? And she basically said, you know, if we are talking about how we move through both dismantling a system and replacing it with something different, we need to be more bold.

And that’s when she introduced the Harm-Free Zone to us, as a project of Critical Resistance. As a way of doing more than running a campaign, but as a way of actually rooting, accountability and abolition in Durham. We started with a Harm-Free Zone committee, which was made up of both organizations and individuals around Durham, the Harm-Free Zone organizing committee.

We began holding community sessions where we were asking community members to envision, you know, what things needed to happen in their community for there to be [00:25:00] accountability without the use of police. We actually had a neighbor, we worked with a neighborhood in Chapel Hill, North Carolina to actually kind of root a Harm-Free Zone for their, within their neighborhood. It was the public housing development.

kai was leaving North Carolina, and she asked us to continue to steward that work here. So she gifted us with all of her materials, and she entrusted the Harm-Free Zone project to SpiritHouse. And we’ve been working it ever since, and it’s been quite a journey.

Mya: Harm-Free Zone is a space where we invite community members who are often the most impacted, a space to dream and conjure and envision what communities could look like if there wasn’t a reliance on the police, and it happens in three parts.

So we have a Harm-Free Zone [00:26:00] transformative justice training, and that space is essentially we, we get into the nuts and bolts of what is community, what is safety, what are our experiences with it? Where have you seen moments where you don’t necessarily need to call in external help? And that space is open for folks who are, this is their lived reality. So it’s oftentimes the majority of people of color justice involved, or folks who have family members who’ve been just as involved, directly impacted folk.

Then there is our media studies group, and that typically is for folks who are not as impacted. So folks who wanna be a part of the conversation but don’t necessarily have any lived experience with it, but they wanna be in the room. And so we first take them through some book studies and documentary studies so that when you enter the room, you’re not gonna unintentionally harm folk with the gaps in your knowledge.

So many times we’ve been in workshop spaces [00:27:00] or community led study groups where well intended folks say some really harmful things, not because they were trying to be problematic, but because they didn’t know any better. And so before we actually invite you into the space to talk to people who were talking about their lived reality, you first need to understand what’s at stake, and you need to understand your actual vantage point where you’re sitting.

And then finally, that space gets the opportunity to decide what they wanna work on. So there’s a direct action element to this. We do our trainings for about 12 to possibly a 100 and 1,000 weeks. We’ve had groups that just are like, no, we don’t wanna stop. And we keep going. And it’s like, okay, but 12 weeks.

But the idea is that from that space, people are able to like, what do you wanna do? We, we now understand so much of this, what happens now? Where do we go from here? And [00:28:00] the direct action piece has been several different things. It’s been folks working on where does the free bus line stop or go? Who has access to it and why? To court mobbing for a young man who was falsely accused of shooting a police. And how do you show up to support that family even if you don’t know that family.

Deana: I know success is on a continuum and we do have stories that have successful outcomes. So can you tell me your favorite success story and what made it possible?

Nia: So we had a young man in Durham who was on his way to work, and he was pulled over by a police officer.

Ultimately, there was a tussle that occurred and the police officer was reaching for his gun, and he shot himself and the young man took the gun and left the scene, understanding that he was a young Black man and there was a police officer who was shot, and that he would not have the space to speak [00:29:00] once other police officers showed up.

So he did not do anything. He didn’t harm the police officer, but he did take the gun and he left. And later in the day, he and his father went to the police department and turned himself in. And of course he was arrested and had a really high bond and never got out of jail. Actually, he was just recently released during COVID after having a 10 year sentence for gun possession, ’cause they never found the gun.

But the charges around shooting the police officer were dropped because, in part because of what we did, which is that, again, it’s another thing that folks talk about now, but this was before it was kind of the thing to do. So we had a list, who’s showing up when, and the courtroom was filled every single day.

And what one of the jurors talked about when they found him not guilty of shooting the police officer, first of all, of course they didn’t have the evidence. But having to look over into at the room and see an entire [00:30:00] community, a very diverse community, sitting behind this young man who knew and believed that he was innocent, absolutely impacted the jurors with their being able to say, well, you know, maybe I need to take a deeper look at this.

You know, because the way that the system is set up and the way that Black, young Black men are portrayed, it would seem to be an open and shut case. The police officer said this young man shot him. The young man said he didn’t. This young man has a record, has a criminal background. Of course, he did it. But because there was so much community support and because the evidence was lacking, he was not guilty of shooting the police officer.

And the system then did what it does, which is, well, we’re gonna punish him anyway. And they gave him 10 years for touching the gun that they had never found. And he actually spent, I think, eight years in prison. Because of COVID, he was released. Many of the people who were sitting behind him who we were able to organize with were people who had been through the [00:31:00] Harm-Free Zone training, or who had been participating in one of the Harm-Free Zone book studies, you know, one of the documentaries.So they understood what was at stake. They understood why it was important for them to be there, and they came.

Alexis: Something that was transformative for me was an experience where somebody who was part of our Ubuntu community was dealing with the threat of violence from a partner who they were breaking up with.

And I don’t think I’m gonna go into the details, but I mean, we talked about it for STOP and at some other places. There was a process of really looking at what it meant to create safety in this situation where the person who was a threat was somebody we all knew. Who the person who needed safety around them in a, in a acute, urgent way, was somebody that we all knew. And honestly also at a time where [00:32:00] Ubuntu was in transition post Day of Truthtelling, and there was also interpersonal drama and all the drama that goes when people fall in love with each other in revolution, then they break up with each other. Then all, all the things.

And for me, that process of really centering this particular survivor, and really listening like, what does safety mean for you? What’s your vision for you, for your kids, for your future, for this, this month, for next month? Really making a space where that person could articulate that and looking at how we could support that very practically was, for me, it was an important moment of bringing it from the theoretical into the place where I actually had to be accountable and take action. And what I noticed was that being a [00:33:00] survivor, there’s kind of this like fantasy of like just there not being any more violence, right? And nobody ever having to go through any of this again. And then we live in this world, and it still is shaped by multiple forms of violence and we still are some of the people most impacted by that.

And so how do we show up for that? Really personally required me to look at my own retraumatization and my projection and you know, I might have had a tendency to project like, well this is what I think this person needs to be safe. We should do this, this, this, this, this. But it actually is survivor led, right?

So we don’t actually know what each other’s ideas of safety are. They might not be exactly the same as the ideas of safety we have for each other and want for each other in every particular moment. And I really felt… like I learned a lot from the way our community showed up and listened and played different roles and [00:34:00] created a context where our community could continue to be our community, and no one got thrown away and this family was able to move forward with its future as a different family.

It was complicated, but I think that it was, for me, an example of a success because I do believe that that survivor did get the version of safety that she envisioned, and a community of people provided that for her, and it, it was also healing for me to think about all of the times that I don’t ask for support. All the times I’ve seen me, my mother, people in my community face similar circumstances without anyone actually listening to what do they, how do they want their situation to be different than what it is, and how can we show up for that? So I’ll, I’ll just offer that [00:35:00] I think it was an early test of what does harm reduction look like when it’s people that we actually know?

Nia: These were actual moments that were transformative for us and for the work that we do. Umar, who is no longer with us, he became an amazing organizer in Durham to the point that the success story that I was gonna share was his, which is a time when there was a domestic violent situation happening. And one of the people called him, and someone in the community called the police, and they got there around the same time. And he spoke to the police who asked him what he wanted them to do, and he said, “I got this.” They asked him to promise that he was gonna handle the situation, [00:36:00] and he did and they left.

Mya: All of the success stories that I can think about all have some iteration of a deep community response. And so every single time there is a showing out, if you will, of community rolling deep for people.

The success story I’m going to share is my own personal success story and our first iteration of Harm-Free Zone. It was about week three, week four. We were barely in. It was around Halloween time. If you’re from Durham, you typically don’t go out for Halloween, like it’s just… cops are everywhere. It’s a little intense.

And we decided we wanted to have a Harm-Free Zone Halloween celebration, ’cause Harm-Free Zone, the community is also super diverse in terms of like intergenerational. So there are folks who have kids, folks who are [00:37:00] in their early twenties, myself at that time included. So we were gonna do a bonfire in the backyard. There was gonna be apple cider. It was very, very cute ’cause I can be very boughetto with my hosting skills.

We had a young man who was a friend of mine and I told this story because it’s actually interconnected with the story we told earlier about the young man who was sent away for this alleged shooting of a police.

Nia: That’s how we got to know the young man that Mya’s talking about, is because he was a cousin of the, the young man who was on trial and then we held onto him, he stuck.

Mya: He wasn’t the only one who felt this way, but he was like, I don’t know if I wanna come out ’cause the police mya…. And I was like, okay, how about this? We are not going anywhere and we’re not going to the clubs. We’re not doing anything. Just come to the house. It’s gonna be everybody that you love there. Like it’s gonna be chill. And after some teeth pulling, he was like, cool. Lovely night. Kids came by, got s’mores and [00:38:00] roasted marshmallows. It was cute.

And at the end we were like, okay, well we feel relaxed, maybe we, we do go out. So a bunch of us were like, we’re gonna go out. Like the night was wrapping. Let’s go to Ninth Street, which is a street very, very close to Duke that’s kind of like food and a couple baby bars. And he’s like, “well, will you ride with me?” and I was like, okay, cool.

So the ride there, breezy, no problem. The ride back, we get tailed and I’m driving his car. We get pulled over and what then proceeds is really ridiculous because the person who pulls us over is also the cop who had been harassing his family, the cop who had shot hisself. What then proceeds is like a ridiculous escalation.

I wanna search the car. And because we had been doing work in the community, we had just made sure that you couldn’t just randomly stop people and search their cars without consent. That was the work that we had been doing and organizing around, being [00:39:00] the brilliant person I am. I was like, I’m sorry, sir, you can’t search my car without consent.

He was like, hold on. And he walked away. He came back and asked me to step out of the vehicle and I was like, why? And then he proceeded to pull me out of the vehicle. Now and I, I often don’t tell this story ’cause it’s, it’s just a lot. But I was thankful for a couple of things before he pulls me out of the car. And one of them is that I immediately, as soon as he walked away from the car, called, I think I called Mama Nia first.

I made a lot of calls very fast. I called Mama Nia and I was like, this is happening. And I wasn’t far from home. Like we were literally, I could have got out the car, it would’ve been less than a mile’s walk to get back to my house. I called her, and I tell her what’s going on. She’s like, okay. Then someone calls my mother, someone calls all the people who just left the bonfire, who all of our folks were at the party we had [00:40:00] planned on going to later on.

And so what quickly happens is the phone tree just lights up, and it wasn’t an intentional phone tree. We hadn’t had a plan around this. But a series of calls go out. So by the time I get yanked out of the car, the phone is still on, and Mama Nia is on the phone, and people are on their way. I just remember at one point, you think you know what you’re gonna do when you have that kind of interaction, and you don’t.

So I was a lot more mouthy than I assumed I would ever be. I had a lot of commentary. My friend was just kind of like, he had been through this so many times that he just kind of shut down. As he’s sitting there trying to figure out what the next step is ’cause this is not something new to him. He’s been, his family has been harassed by this police officer for months, at this point.

I’m just like, “I know my rights.” And at one point I just remember hearing my phone go off and the officers who had now come up behind us didn’t realize my phone was still on. And then [00:41:00] like a scene out of a movie, cars start cresting the hill and it’s my community. They have now shown up, and the community lawyer is like, “Mya, stop talking.”

And I’m like, bet, haha, gonna stop talking now. The Harm-Free Zone cohort is here, like they have now arrived. I didn’t even know that they trailed us when they took us in for processing. They trailed the car. They have now set up camp and Halloween costumes in the lobby of the jail. And the community lawyers like talking to the magistrate like, “what’s going on?”

Because of course, in a story like this, there have to be a lot of hiccups. So like, you didn’t read me my rights. You didn’t have a reason to pull me over. All these things happen. There’s a sense in the jail like, who the hell did y’all pull in? Because what the hell is happening? There’s a whole bunch of people. There’s Mary and Joseph, there’s a bottle of Sriracha, like there’s just a lot of mayhem happening [00:42:00] and we don’t know why, and they let us go. And kai was there.

I just remember feeling this deep sense of relief, of course, but also feeling very humbled by community. No one had to show up. People have their own deep trauma responses to jails and policing and what have you. And without question, people shut down a whole party, made an announcement on on the DJ set and was like, yo, this is happening to community members. Some of us are riding out, y’all down? And people came.

Yeah, that’s one of my favorite success stories because the conditions that we set, and I think this is really important, the conditions that we set via the Harm-Free Zone by way of Ubuntu, by way of SpiritHouse, set the conditions that made it possible for us to be released in a matter of hours.

And those conditions don’t always exist for everybody all the time, right? But at the time, [00:43:00] we had been doing a lot of work. And so it was almost like this question of like a David and Goliath kind of moment where it’s like, do we really wanna go up against those small but mighty people? And the answer was at the time, no.

Like, no, we don’t wanna start that kind of smoke. No, we don’t wanna get into that kind of fight because we know we’re wrong. And so we’re gonna give you your folk back. And so often people don’t get that opportunity to get their folk folk back. And even after that, when we had to go to court later, people showed up. People showed up, consistently showed up.

For me, that’s a healing moment. And I remember it was a healing moment for another dear friend who no longer is with us Umar who had been incarcerated and he was like, so many of my homies didn’t, don’t get to come out to that kind of welcome of community. You know, like we come back, we come home, we come out from behind the wall and no one’s [00:44:00] there. No one shows up like that. And y’all were there.

For that moment to be such a healing, cathartic moment for him, as well. Yeah, it really shifted a lot about how I wanted to move moving forward.

Alexis: Yeah. I’m over here crying. I just love you so much, Mya.

Nia: I love you Mya Hunter, thank you for being willing to share that.

I think one of the things that I think is most important about any of this work is how relational it is because it wasn’t just the fact that folks got more of a shared language or shared knowledge. That’s important, but we also love each other. We also love each other. Those people showed up at the jail, not just because of what they’d learned, but because they love Mya. And they showed up to court mob, not just because of what they learned, but because they love us and they trusted us to say, show up for [00:45:00] this family who we now love.

Umar showed up for a friend who he loves and told the police to stand down, that he got this.

Deana: I just wanna thank you for those really powerful stories, and especially to you, Mya, for bringing that deeply vulnerable story to this conversation. What it feels like to have a win in this work, that is not only individual, but collective and how life-changing and moving that is for everyone who’s a part of it.

It also makes me think about how challenging it can be to get there. Can you tell us about a challenge that you remember and how the challenge grew your work?

Nia: For me, the most important thing about all of this is not just having the knowledge, it’s being willing to be messy. ‘Cause like Alexis said earlier, there’s a lot of messiness we not talking about in Durham, everywhere I’m sure.

Because we don’t have a…a roadmap and a model for any of this. What it [00:46:00] means to be accountable to each other. We try, but we mess up all the time. We all do. So there’s been a lot of…there’s been harm that we’ve had to work through, but the love, even in the midst of harm, the love doesn’t waiver. And our commitment to transforming this place and it being a model for the rest of the world, that’s our commitment.

That’s one of the commitments we made with Ubuntu, that we were gonna transform Durham, and it would be a model for the rest of the world. And you know, we ain’t perfect, but we’re still working it.

Alexis: There’s this question of growth, you know, and how community can grow around a set of values. And then what happens when we create something that’s so longed for, you know, like it’s been needed.

I think our souls know that we need it. For centuries, it’s been needed, and people have been living without it. And [00:47:00] there’s this shine and this radiance and you know, Mama Nia and Mya know like everywhere we went, everywhere we still go. People are like attracted, you know, like, oh my goodness, this is what community’s supposed to be, and there’s so much love here.

And I do feel like there have been times where that growth, it’s not like everybody can then get the Harm-Free Zone training right away and then interact with community after that. And they’ve totally internalized it. And then they don’t have any coping mechanisms that are gonna come up, and then they totally never can be re-traumatized again because the love is just that strong, you know?

I wish it was like that, but we’re like, all getting triggered all the time, you know, like you know, Audre Lorde, one of my favorite poems by her is called Call, and she says, we are learning by heart what has never been taught. I experience that all the time. You know, I…I think that that is what is happening.

And the learning by heart part means that [00:48:00] there is this profound vulnerability. Like it can be heartbreaking to feel like, oh, but we did all this work, and it didn’t prevent somebody in our community still being harmed by the state. You know? And it can be heartbreaking to see people within our formations harm each other.

You know, because they actually are using their survival mechanisms that are, you know, forged out of violent situations on other people, and it’s violent. All of those things have happened and, at the same time, I think that the fact of that and then seeing us come together in the face of that and the messiness not being an excuse to be like,”well, you know, like, I guess it’s not possible”.

You know, like just not, not giving up on the possibility and still being like, you know what? Even in the situation that I was talking about in [00:49:00] terms of that success story, like I was mad at the person and it was like, well, you know, it actually matters more. You know, your safety matters more. Possibility of: our freedom matters more.

And it is relational and it is social, and it is not separate. It’s not like our social lives are separate from this work, in…in any way. There’s something about building this practice of abolition that has me show up when maybe, do I like everybody, or was this cute? Was this not cute? Does it all make sense? Would be like, I’m not gonna show up. Right? It has me still show up, and I’ve seen it allow the work to move forward and allow each of us to grow in ways that are really powerful. And and the thing is that it’s healing because we are real people, [00:50:00] and we’re not perfect. and we’re holding generations of people who weren’t perfect.

We’re thinking about our parents who weren’t perfect, and our siblings or people from our past who weren’t perfect. And then here we are with some more people who aren’t perfect ,and there’s another possibility because of our shared commitment. And just because we understand that we’re in a practice to create something that we actually haven’t experienced before. We got to experience pieces of it. And the embodied memory of experiencing a reality that was different than anything that we could have imagined or had experienced before is so strengthening. You know? It…it makes so much possible. It’s why it’s so worthwhile to be in practice.

Mya: I feel like the trial and error portion of the show, we don’t talk about enough.

Like, it’s like, oh, here’s my very lofty, beautiful, succinct thought about how we’re gonna change the world. [00:51:00] Okay, go do it. And it’s like, all right. And then it’s like, wait, you didn’t tell me that if I do this, it might make people mad. I might fail, I might tumble, I might do things wrong. And then you are struggling internally with a lack of perfection, of meeting the ideal.

And I think that’s really, really hard. And we don’t talk enough about the grace that is required. When people talk about grace, you know, we talk about like heavenly grace, but like giving people a moment to catch the rhythm or like figure it out or stumble. This is jazz. This is not a classical piece. It is jazz.

It requires a lot of improv and people adapting to what’s happening. And I love us. I love us so much. And this community sometimes feels microscopically small because we’ve been in it for so long with each other, and our roles in it have shifted. Our positionalities have shifted, but we do not allow for adaptations.

Like [00:52:00] we don’t allow ourselves to adapt sometimes, but we wanna get into conversations about sustainability. Right. It’s like how do we make sure that the vision lives on? And it’s like, well, the vision might have to adapt for the place and people’s understanding.

I’ve been sitting in a lot of deep contemplation about how do we do this? Not well in the sense of we did that right, but well, in the sense of like, I wanna be healthy and whole and sane on the other side of it. And I think we can offer that gift to ourselves. We don’t have a lot of space for that conversation though when everything feels super urgent. Everything is pressing, everything is telling us to go faster. Go get louder, stretch thinner versus go deeper. Maybe get stiller, talk softer.

Some of my struggles have been like, where am I in my practice? [00:53:00] Liberation as a practice. Abolition as a practice beyond the principle idea of it. If I can’t do it this way, what does that mean? I’ve really been sitting with that. Like, what are boundaries? Whew. That’s a whole other podcast. Boundaries and movement.

I just, I feel deeply that, deeply we wanna be right because it feels like it’s a life or death scenario. If we’re not, if we don’t get it right, this, this time, what happens if we fail? And so much of everything, conversations about the left, the right politics, the elections, all of these things, the policies are steeped in our scarcity and urgency, and it feels counterintuitive. And sometimes I’ll even say shameful to be like, actually, I think we should take a moment to take a deep breath, find some level of softness for each other, and then re-enter the conversation. Like, how dare you say that to somebody? [00:54:00] Who is struggling? How dare you say that “My house is on fire.” And my response to that is like, “yep, it’s been on fire.”

Like I have to believe in the quantum physics moment that two things can exist at once. Multiple things can exist at once. Multiple things can be true, and there’s still space and time. The things I struggle most deeply with are feeling like I know we can find a path to a world without prison. Find a path to liberation.

We’re walking the path, not find it. I mean, I feel like we’re on it. We’re…we’re walking it. We’re treading it for generations to come because people have already cut some really clear paths for us. My own personal feelings of inadequacy. When I don’t seem to meet the bar that I feel like people have set and these beautiful tones of how you get this right, how you don’t mess it up.[00:55:00] Like it’s humbling.

Nia: As someone who has been…now practicing for more than a decade, “leave no one behind” is a challenge for the movement. When we first started, we were all fairly new and so there was more room for hiccups. There was more room for folks’ humanity. There was more room for understanding that most people around us had no clue.

I don’t always see that patience in our community right now. Almost as if we assume that others have been in this as long as we have and therefore should be getting it. We don’t always allow for the grace, as Mya used…the word Mya used, [00:57:00] for those who are still resistant.

Even after witnessing some of the things that they’ve witnessed, they are unable to see a liberation that doesn’t include punitive punishment. So I feel like we make mistakes and it actually causes rifts in the way that we move. So it’s very interesting to be in a deep relationship and love someone who you just fundamentally disagree with on the process. On how to move something forward and wind up on actually opposite sides.

And that happens. That has happened here more than once. And it’s kind of this weird space to be in, to look across the room and be like, I love you. I know you. We [00:58:00] have built community together. I love your children. And what you are doing, I believe, is harmful and I can’t cosign. It’s hard to even describe what that is, what that feels like to be that at odds with someone who you have built community with.

For me, I see it as a space of a willingness to let people go. There is a willingness to say, you know what? I’ve, after all this time, I don’t necessarily feel like we can bring everyone with us, and so we need to cut them off. I fundamentally don’t believe that. One of the last things that Cynthia Brown said to us before she transitioned was, “leave no one behind.”

We were surrounding her [00:59:00] in the emergency room as she spoke her last words to us, and that was one of the things that…the gifts that she gave us. But that’s not easy. It’s absolutely not easy, and because of the fact that we have been in practice so long and have embodied accountability as a practice. Abolition is a practice. Love is a practice, and so we’ve been in practice so long. It makes it difficult to be in relationship with people, who not only are not in practice, but who are resistant to the practice.

And to know that you still have to stay, that you still have to try to make time and space because none of us, we didn’t learn this thing and then we have it right. We had to be in practice. Like I said, it’s more than a decade for me, and I’m still in practice. So having to make that space for other people [01:00:00] when we are this far into practice sometimes is difficult. And it would be easier, particularly if like politically, we have the votes to pass something that we know should be passed.

And I feel like it’s difficult and I feel like it is where we are. And it’s the next thing that we have to figure out how to continue to move together. Sometimes we have to make that decision or make that choice, and I don’t even know what an answer is to that. Right? Because it’s not like you’re passing something that is bad.

And so what we do in that space, I’m not sure of this. I think this is one of the places that we’re in right now where we have gotten to a place where we have some power in certain places where our most progressive people are… actually have power and can make policies and practices that benefit our community, and other folks in our [01:01:00] community who see it as harm.

That we’re in that space now where we have to look at that. It was one thing to not have any power 10 or 15 years ago. It’s another thing to have the power now and to say, okay, how do I actualize using this in a way that still does not harm anyone? That leaves no one behind? And so I feel challenged by that.

Deana: Before we get to the credits, we wanna give you a gift. Here is Alexis Pauline Gumbs reading her poem titled “wishful thinking”, or “what I’m waiting to find in our email boxes.”

Alexis: It really started out as an email because at the time that we were responding to the, the Duke lacrosse case. I was a grad student at Duke. I was getting these emails and the university was just fully taking a pro-rape stance. And so I was like, you know what I, these are the emails I would, I was receiving. And I ended up sending it as an email [01:02:00] to Ubuntu. And then it was kai who was like, will you actually say this out loud on The Day of Truthtelling?

So that is the context. And I’ll also say I was inspired by some work that Mendi & Keith Obadike did, two of my favorite artists ever, and who have become mentors, who created something called “wishful thinking,” and it was their response to the police murder of Amadou Diallo.

This is “wishful thinking” or “what I’m waiting to find in our email boxes”.

- you wake up each day

as new as anyone

there is no reason to assume

you would be supernaturally strong.

there is no reason to test your strength

through daily disrespect and neglect.

you [01:03:00] don’t need to be strong.

everyone supports you.

- if you say ouch

we believe that you are hurt.

we wait to hear how we can help

to mend your pain.

- you have chosen to be at a school,

at a workplace, in a community

that knows that you are priceless

that would never sacrifice your spirit

that knows it needs your brilliance to be whole

- your very skin

is sacred

and everything beyond it

is a miracle that we revere

- we mourn any violence that

has ever been enacted against you.

we will do what it takes

to make sure that it doesn’t happen again.

to anyone.

- when you speak

we listen.

we [01:04:00] are so glad that you

are here, of all places.

- other women

even strangers

reach out to you

when you seem afraid

and they stay

until peace comes

- the sun

reminds everyone

how much they love you.

- people are interested

in what you are wearing

simply

because it tells them

what paintings to make.

- everyone has always told you

you can stay a child

until you are ready to move on

- if you run across the street

naked at midnight

no one will think

you are asking

for anything.

- you do so many things

because it feels good to move.

you have nothing to prove

to anyone.

- white people [01:05:00] cannot harm you.

they do not want to.

they do not do it by accident.

- your smile makes people

glad to be alive

- your body is not

a symbol of anything

- everyone respects your work

and makes sure you are safe

while doing it

- at any moment

you might relive

the joy of being embraced

- no one will lie to you,

scream at you

or demand anything.

- when you change your mind,

people will remember to change theirs.

- your children are safe

no one will use them against you.

- the university is a place where you

are reflected and embraced.

anyone who forgets how miraculous [01:06:00] you are

need only open their eyes.

- the universe conspires

to lift you

up.

- on the news everynight

people who look like you and

the people you love

are applauded

for their contribution to society.

- the place where knowledge is

has no walls.

- you are rewarded for the work you do

to keep it all together.

- every song i’ve

ever heard on the radio

is in praise

of you.

- the way you speak

is exactly right

for wherever you happen

to be.

- there is no continent anywhere

where life counts as nothing.

- there is no innocence that needs your guilt

to prove it.

- there is no house

in your neighborhood [01:07:00]

where you still hear screams

every time you go

past.

- no news camera waits

to amplify your pain.

- nobody wonders

whether you will make it.

everybody believes in you

- when you have a child

no one finds it tragic.

no map records it as an instance of blight.

- no one hopes you will give up

on your neighborhood

so they can buy it up cheap.

- everyone asks you your name.

no one calls you out of it.

- someone is thinking highly of you

right now.

- being around you

makes people want to be

their kindest, most generous selves.

- there is no law anywhere

that depends on your silence.

- nobody bases [01:08:00]

their privilege

on their ability to desecrate you.

- everyone will believe anything you say

because they have been telling you the truth

all along.

- school is a place, like every other place.

no one here is out to get you.

- worldwide, girls who look like you

are known for having great ideas.

- 3 in 3 women will fall in love with themselves

during their lifetime.

- every minute in North Carolina

a woman embraces

another woman.

- you know 8 people

who will help you move

to a new place

if you need to.

- when you speak loudly

everyone is happy

because they wondered

what you were thinking about.

- people give you gifts

and truly expect nothing

in return.

- no one thinks you are

over-reacting. [01:09:00]

- everyone believes

that you should have all

the resources that you need,

because by being yourself

you make the world so much

brighter.

- any creases on your face

are from laughter.

- no one, anywhere, is locked in a cage.

- you are completely used to knowing what you want.

following your dream is as easy as waking.

- you are more than enough.

- everyone is waiting

to see what great thing

you’ll do next.

- every institution wants to know

what you think, so they can find out

what they should really be doing,

or shut down.

- strangers send you love letters

thanking you

for speaking your mind.

- you wake up

new

as anyone.

Deana: We would like to thank the powerful [01:10:00] organizers who live and work in Durham, North Carolina, who grind every day to make this world a better place for all of us. As always, I encourage you to take the lessons you learn today and keep practicing.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative want to share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems. Find the link in our show notes to learn more. Stories for Power is presented by Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative executive produced by Mimi Kim, Shira Hassan, and Rachel Caidor.

Produced by Emergence Media. Audio editing and mixing by Joe Namy and iLL Weaver. Music composed by Scale Hands and L05 of Complex Movements in collaboration with Ahya Simone. Stay tuned for more episodes of the Stories For Power Podcast. Check out our [01:11:00] show notes and go to StoriesForPower.org to learn more.