[00:00:00]

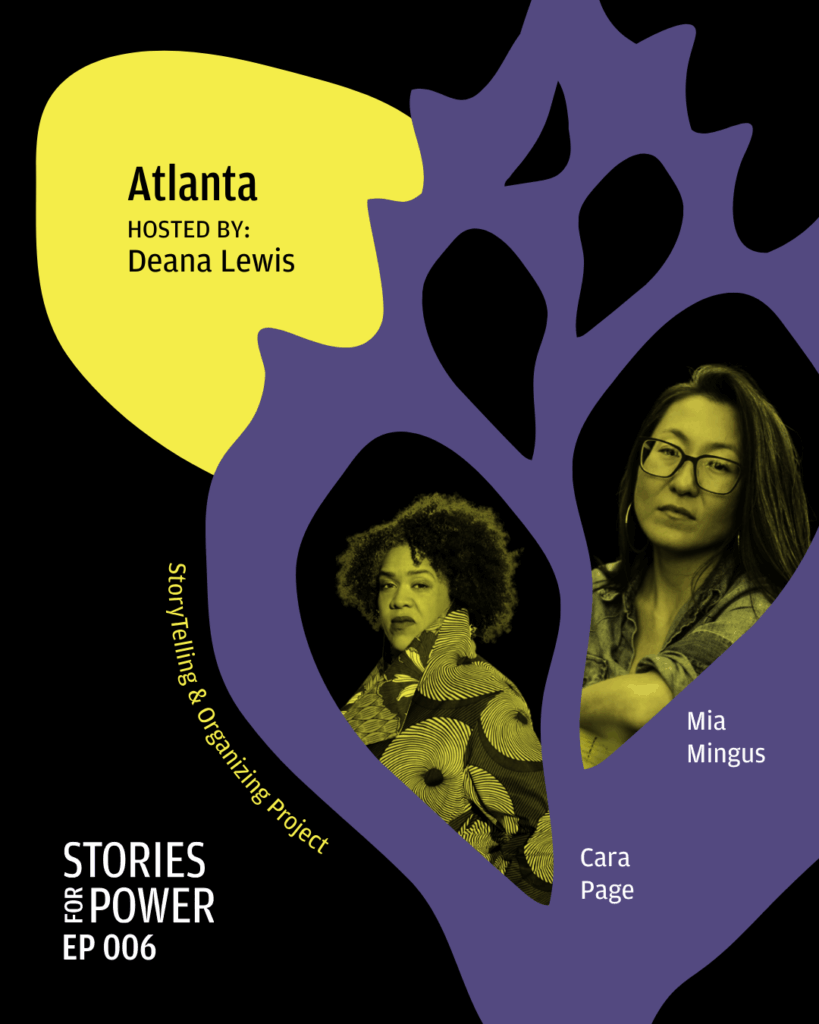

Deana: Welcome to Stories for Power. I’m Deana Lewis and I’m a member of Just Practice Collaborative. Stories For Power is an oral history project produced by Just Practice Collaborative and Creative Interventions. It explores the political lineage and historical experiments that gave way to this wave of transformative justice, community accountability, and prison abolition.

In each episode of Stories for Power, we speak with activists and organizers from different cities who were and continue to be at the forefront of feminist abolitionist praxis. They talk about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the early 2000’s through 2010 and how their work informed abolitionist transformative justice and community accountability organizing today.

Don’t worry, if any terms or [00:01:00] words have you confused, we’ll do our best to link to resources in the show notes. And you can always go back to listen to the special introduction episode for more context.

In this episode, you’ll hear from two inspiring abolitionist feminists, Mia Mingus and Cara Page. We will talk about the courageous and radical work they were part of in Atlanta between the early 2000’s and 2011.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems? Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

A note for our listeners, we’ll be discussing violence including police violence, intimate partner violence, and community violence. We encourage you to take care of [00:02:00] yourself, and we understand that taking care of yourself can also look like not listening to this podcast until you’re ready.

Now let me introduce our guests. They have amazing and extensive experiences and knowledge. I’ll do my best to summarize, we have linked their full bios in the show notes. You can also learn more on our website StoriesforPower.org.

Cara Page is a Black, queer, feminist, cultural and memory worker, curator, and organizer. For 30 plus years, she has organized with Black, Indigenous, and people of color, queer, trans, lesbian, gay, bi, intersex, gender non-conforming liberation movements in the US and Global South, at the intersections of racial, gender, and economic justice, reproductive justice, healing justice, and transformative justice.

She’s the founder of Changing Frequencies, an abolitionist organizing project that designs cultural memory work to disrupt harms and violence from the medical industrial complex, [00:03:00] also known as the MIC. Their vision is to amplify and honor communal stories towards healing and transformative futures.

She’s also co-founder of The Healing Histories Project and co-founder of the Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective. Cara, along with Erica Woodland, co-edited the book Healing Justice Lineages: Dreaming at the Crossroads of Liberation, Collective Care, and Safety.

Cara: I’m Cara Page, she /her /hers. I’m a Black queer feminist organizer now living on Lenape Munsee land in Brooklyn, New York, and formerly living in Atlanta, Georgia, and Durham, North Carolina.

My people are from the South, of the South. I am of the South, as well. I was doing work at that time, new emerging work with the Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective, which is, it still exists, a collective of healers, health [00:04:00] practitioners and organizers and cultural workers seeking to build strategies around interrupting generational trauma from violence, colonization, and slavery through understanding ways to build mechanisms of healing, care and safety for our psychic, environmental, spiritual, physical, emotional wellbeing.

It was particular in the South and all of our work was place-based, including building with the Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative.

Deana: Mia Mingus is a writer, educator, and trainer for transformative justice and disability justice. Mia founded and currently leads SOIL, a transformative justice project, which builds the conditions for transformative justice to grow and thrive. She’s an abolitionist and survivor who has been involved in transformative justice work for the last two decades, and believes we must move beyond punishment, revenge and criminalization if we are ever to effectively break generational [00:05:00] cycles of violence and create the world our hearts long for.

Mia: Hi, I’m Mia Mingus. She/her pronouns, and I am calling in from Muscogee Creek land, specifically of the Lower Muscogee Creek tribe, otherwise known as McDonough, Georgia. During the time that we are talking about in the Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative time, I was part of the emerging reproductive justice movement and particularly during the ATJC, the Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative’s time, it was an exciting time ’cause reproductive justice was making its way onto the main stage in the country. So I was part of Georgians for Choice initially, which is how I got in… connected with and involved with the ATJC, and then later that transitioned into SPARK Reproductive Justice NOW.

And I was also [00:06:00] helping to create and then forward the disability justice framework, which had not existed as a articulated framework before then. Although of course, as always, the work has always been going on. But I was based in Atlanta, and I grew up in the Caribbean on St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands, a territory of the United States, a colonized, occupied territory. And I am a queer, disabled woman of color, Korean adoptee.

Deana: So thinking about Atlanta, at the time you were with these different projects, can you talk about the broader historical context in the city and in your communities?

Cara: So what’s important to note is a few things at that time, right? We were looking at post 9/11, right? And the increased policing and surveillance and fascism and Islamophobia in the country. And what that looked like, in particular, in the South in the early two [00:07:00] thousands was a immense anti-immigration reform, popping off anti-abortion laws popping off. Campaigned against the shackling of pregnant people incarcerated, was a huge topic alongside abortion. And we were also looking at increased anti-Black racist violence and increased anti-Muslim violence targeting, in particular, families in community businesses, Muslim businesses that were being perceived as meth drug sites.

And we also were quickly responding to the mayhem of the hurricanes of Katrina and, and Rita, during that time. Those two hurricanes, obviously everyone knows about Katrina, but the impact of those for the South, in particular, is understanding how we were responding to the carceral state response, and not the storms, but [00:08:00] the immense racism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, you name it, all the things. And how the police came in and the state came in and targeted our Black and brown communities, immigrant and refugees, and just caused mayhem to our people. Because Atlanta was such a big city, we took on a lot of people that were getting… were pushed out of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast during that time.

But I just wanna add, before I toss it to Mia, is we also had a particular awakening around organizing. Because Southerners on New Ground, Project South, Sister Song, a reproductive justice women of color organization, and Sister Love, the first Black women HIV AIDS organization. All of these organizations were in Atlanta, Georgia. And Georgians for Choice, that was having a major awakening in their political strategy. And so watching the emergence of new political strategies and these organizations have become historical pillars to major organizing work that [00:09:00] changed the game during that time.

Mia: And I would also add to all of the brilliance that Cara just shared. I think for us doing reproductive justice work, well one, there was a big shift happening internally in reproductive rights, health and justice that was not necessarily in the mainstream yet, where there was Sister Song and Asian Communities for Reproductive Justice were forwarding the reproductive justice framework.

And before that, people were not using that term. I know now it seems old hat and everybody’s saying it, but it was really such a huge shift to move from thinking about these individual rights, like individual abortion rights, for example, to a more collectivized, communal, broader systemic understanding of moving beyond just abortion, including population control, including forced sterilization, et cetera.

But I think, in particular, to [00:10:00] Atlanta, one thing that’s really important to know is that this was also at a time when Georgia in particular, was being used as a precedent state where the most harshest, reproductive oppressive laws and policies were being passed here because they knew that they would pass, and then it could set a precedent for them to sweep across the rest of the South and the Midwest together. And that the South and the Midwest, our histories around reproductive oppression are so similar and so deeply tied together. And so, you know, when I came to first start working at Georgians for Choice, which then later became SPARK Reproductive Justice NOW, that was the climate, and that was the environment in which we were going down to the Capitol and trying to fight against these terrible bills that we knew it was a losing battle.

Both and, at the same time though, I think that for me, like coming into [00:11:00] TJ work was just an awakening, and I think this was parallel with all the things that Cara was mentioning in terms of the movements and the resilience that was happening, was that there was a broad shift moving from just resistance to how do we not only resist, but how do we also build the world that we actually want and that we actually desire? And what does that look like?

And that… that shift, which we now know is so in line with abolition and is so in line with much of the work that we see happening. But I think at the time though, a lot of people hadn’t thought about that. And so being in such a repressive state in terms of reproductive oppression, in particular, it was such a moment of then coming to TJ work, et cetera.

But I also wanna just throw out that in addition to these organizations that were doing amazing work, there were also all of these new frameworks that were emerging as well. There was obviously transformative justice and community accountability, but there was also [00:12:00] reproductive justice, like I talked about. Healing justice, obviously, which Cara can speak more to, with Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective, as well as disability justice. Which I know now disability justice and healing justice are terms we use all the time. But they were very new. Not just the terms, but the frameworks, and the political visions that they were putting out were very, very new. And I think radically shifting the political landscape upon which our movements were building our dreams.

Deana: So we’re really talking about the moments where healing justice and disability justice are coming into our practice. Cara, I would like to hear more about what started Kindred. What was happening at that time?

Cara: Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective came out of just a moment of witnessing in the South, in particular, grief and burnout inside of movement from loss. Loss of freedom fighters, loss of campaigns. People were just [00:13:00] tired, right? Because as much as the power that we were building was happening on the ground that Mia spoke to, we were also getting pummeled, right?

Again, by all this legislation, all this, I call it fascism, and just like all the conservatism that, that, that was landing on these Southern states, as you said, Mia, to set precedent, and Georgia was holding a lot. Because also in addition to the, anti-abortion laws were the anti-immigration laws, right? They were running neck and neck.

And Kindred was speaking to a particular moment where we said, wait a minute. What does it mean to organize healers and health practitioners to respond to generational trauma in this moment from a legacy of violence by the state and communal hate violence, as well, that we were also seeing increase based on anti-Black racism and Islamophobia, as I mentioned, and just white supremacy.

I’ve been in the South since the late 90’s and really [00:14:00] watched an absolute increase of violence in the Southeast. Between 2001 to 2005, it was just, it was rampant. Because the country was responding to a… a mass conservatism and increase of policing, surveillance, the Patriot Act, all these things that were blowing out in this Bush era so that everything happened so quickly, people didn’t have time to lay it down and say, okay, where do we grieve? Where do we take care of each other in relationship to the political organizing that we’re doing? And what does care and safety look like on the ground?

So we were literally moving in teams with healers and transformative therapists, nurses, and doctors who were willing to say, “we don’t want to be complicit with state.” We know our people don’t go to hospitals or clinics. How do we make sure we’re in and at mobilizations and rallies, providing care strategies on the ground as part of safety, as part of organizing at all these massive rallies and demonstrations we were holding [00:15:00] at that time? It was a vibrant time, but it was a painful time.

But Kindred was both responding to the need on the ground for strategy and integration of care alongside learning. Let me be clear. We were learning from disability justice. We were learning from harm reduction. Shout out to Shira Hassan’s book and liberatory Harm Reduction that we were trying to apply to healing justice.

Where are we challenging the ways care has made our communities expendable? And disability justice offering the question of how do we build interdependence? When we talk about care strategies, how do we not leave anyone behind and make sure we are honoring different ways of people are living inside of their collective bodies and experiences?

I hope that speaks to it more, but I will say this. Kindred, in particular, was deeply, deeply informed and shaped by the legacy and political thinking of harm reduction, the environmental [00:16:00] justice movement from the Global South, disability justice, reproductive justice, which I too am a movement leader in reproductive justice, and that was deeply the roots of my work. Which led me to believe we needed healing justice because I understood the way we were looking at care and health was sometimes very limiting and not looking at ways we’re talking about healing and care for each other and ourselves. And then transformative justice in terms of how are we talking about trauma, period.

With health practitioners, how are they holding trauma and survivorship that allows for the autonomy and consent of survivors of sexual assault, of sexual abuse, of child sexual abuse, and understanding that that disconnection was not making itself to archaic ways of medicine that were being taught where you’re asking health practitioners to be on the front line of working with survivors, but not being able to question their analysis or ideas [00:17:00] around survivorship, and thinking about strategies with health providers, social workers and therapists that was not complicit with state mandatory reporting around abuse.

That’s what we were trying to lay down.

Deana: That was a huge overview with a ton of information, and it was amazing. So I just wanna ask, how do you and Kindred define a healing justice framework?

Cara: It is a response to generational trauma in relationship to how do we build care strategies that support and sustain our emotional, physical, psychic, environmental wellbeing. And learn more in the book Healing Justice Lineages that’s just coming out, ’cause it breaks it down. It’s a little bit wider than what I just told you, but that’s okay.

Deana: Mia, tell me a little bit more about what kicked off your work. What were you responding to?

Mia: So I came to the [00:18:00] ATJC. I was a very young organizer at the time. I was green and young at the same time. I was in my…my like early twenties or late early twenties.

And so I was part of Georgians for Choice, which at the time was a statewide coalition. They had not only folks who did reproductive health, like direct services, like abortion providers for example, or clinics, but they also had folks who did reproductive rights work in terms of legislative work and working on policies and then reproductive justice folks, as well.

And so it, in that coalition, they also had organizations who were in solidarity with that work and who were doing the work of supporting reproductive freedom, in general. And so Raksha, who was the Atlanta organization that housed the Breaking the Silence [00:19:00] project that was started by Sonali Sadequee and Priyanka Sinha, they were the ones who partnered with generationFIVE and Sarah Kershner, in particular. And so it was that partnership that began the process of what became the Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative. And so I was sent as a rep to that meeting because everybody else was busy and they were like, there’s a community mapping meeting that you know one of our members is having and you should go to that. So I said, “okay, I’ll go.” And it was just the turning point, I think, for the rest of my life. And from that community mapping, out of that became the launch committee, which then turned into the ATJC.

Let me back it up and just say that Raksha is an organization in Atlanta that works specifically with the South Asian community, and so does a lot of work around racial justice, around immigrant [00:20:00] justice, et cetera.

They primarily had been working around domestic violence or adult on adult violence, so sexual assault, et cetera. But the Breaking the Silence project began when Sonali and Priyanka really saw a need to address child sexual abuse. They were working with so many different folks, so many different survivors, so many different cases.

And within that, there were many instances of child sexual abuse, as well. And there was really nowhere to hold that. And you know, like many organizations like Raksha, they were also at capacity and, you know, struggling for resources.

And so BSP, the Breaking the Silence project, from that was the seed that then connected with genFIVE. And then that’s what really birthed this vision of we need a way to respond to child sexual abuse that is not reliant on the state because the communities that we are [00:21:00] working with within Raksha cannot rely on the state. It’s not like they have a choice. It just wasn’t even an option. And so I think that became fertile ground and site for us to… to figure out like, can we really do this? What would that look like here in Atlanta? What would that look like from a Southern perspective? And so that’s really my organization and my entry point.

Deana: Yeah. You’ve talked about really important frameworks that are necessary in your work. In our work, I would really love for folks to hear what disability justice and reproductive justice mean in your own words.

Mia: Disability justice, what’s so wonderful about it now, I think, is that lots and lots of folks are practicing DJ and are doing it in lots of different ways. So there’s different ways that people are defining it, I’m sure. For me, though, I still always come back to, disability justice is a multi-issue politic, meaning it’s intersectional way of [00:22:00] understanding what liberation would look like for disabled communities and our people. That disabled people are connected to communities. So it’s not only about only just disability. And so disability justice was really looking at how do we move away from the single issue ways of understanding that that just compartmentalize people because, especially for so many of us who were disabled, people from multiple oppressed identities and experiences, we’re not fitting into the very narrow definitions of the disability rights movement, for example.

And so disability justice was a way to understand that ableism and able supremacy are bound up with other systems of oppression, as well, and that we can’t end ableism, for example, without also ending white supremacy, without also ending patriarchy, without also stopping the environmental degradation we’re facing, et cetera, [00:23:00] et cetera. And so in that way, disability justice is about moving away from just individual rights to more collective liberation.

When I think about reproductive justice, for me, reproductive justice is about a similar move, from moving beyond just this very narrow group of issues like abortion, sometimes maybe including family planning, sometimes maybe including pregnancy, et cetera. But that was it.

And so reproductive justice is beyond abortion, moving into a more collective liberation framework, that’s beyond just individual rights. And also not looking to the courts as our sole place to have liberation, and as the sole provider or understanding of liberation. Because so many communities, they never look to the courts and the government as their protectors. They need protection from the courts and the government.

And so reproductive justice included things [00:24:00] like right to parent, the right to not have children. Included things like looking at systemic oppression as connected to and as a part of what reproductive justice means. And so it’s not only about, you know, these one-off issues, it’s about looking at the entire thing, and that healing justice is a part of that, that disability justice and queer liberation and trans liberation is a part of that.

What was so powerful about this moment was that all of these movements were really expanding the broader movement for liberation. And in that way, inviting more and more people into our broader movement for liberation, because now there was a place for them – frameworks through which they could understand their lived experiences, and through which they could then be able to connect with other people.

Not only welcome them, but like gave validity to the work that they were already doing. That, you know, I think about [00:25:00] healing justice, that the work that healers were doing, that that was a powerful part of liberation. That the ways in which disabled people were creating care networks or creating access for each other, that that was a crucial part of liberatory work and it was not separate from our movements for liberation.

Deana: Yeah, absolutely. It’s really powerful and it brought us out of our silos and really connected us. Cara, how about you? How would you define reproductive justice?

Cara: I entered through a lens of anti-eugenics and population control. So wait, let me go back real quick… because I’m kind of like a OG when I think about it.

Like I knew some of the people that lead RJ when they were just in their own awakening stages, right? I worked with Loretta Ross at the National Black Women’s Health Project, and I sought out leadership like Byllye Avery at the National Black Women’s Health Project in the ‘80’s. I felt that Black people were looking for [00:26:00] a way to think about health that was transformative. And they were talking about healing, whoops, surprise – healing and care in ways that I thought were dynamic and interesting.

Then I didn’t realize homophobia and transphobia and, you know, all the things that would emerge inside of a Black health movement in this country that I feel are some of the tentacles that lead towards reproductive justice. I have a very particular experience living in a Black queer body and a lived experience, and what we were all experiencing, if you watch the progression in the ‘80’s of women of color health organizations and the movement that was emerging, I guess I’m saying reproductive justice was inevitable.

Because there were…there were Asian organizations, you know, Latinx, I’m not remembering all the names, so sorry, but they were emerging to speak to the disparities of healthcare and then, of course, the HIV AIDS epidemic that changed the game, [00:27:00] right?

So reproductive justice for me, I entered it through a lens of working on AIDS for Black women, for queer people, for trans people, for people living on the street, for a survival economy. That we were trying to figure out, how do we keep our people alive? Somewhere in here I met Young Women’s Empowerment Project, you know, shout out, you know. The journey was long.

I appreciate, Deana, you saying to transcend silos. Because things were very siloed. I came out of the anti-violence movement. That’s one of the most siloed parking lots to be in. And so to find reproductive justice was both an awakening to see more dimensions of the reality of how I birth, when I birth, what families I want to create, what families I choose, what families I’m trying to build access for or build power with.

It changed the game on that level. And, reproductive justice was a direct confrontation to the implications of [00:28:00] population control in this country. The rise of sterilization abuse, the misuse and exploitation, experimentation on Black and brown people for the sake of building big pharma and the reproductive health medical industry in this country.

So reproductive justice also wrestled with how are we gonna push up against this perception that some of us are only born to reproduce for the white, wealthy, able bodied Christian elite? Right? So like reproductive justice came out of that like a very anti-eugenic frame, a very anti-pop[ulation]-control frame that said, we will not let our bodies continue just to be criminalized and used to reproduce solely for capitalism.

And how will we decriminalize ourselves by saying we want to birth for the power of ourselves. We want to raise families for the power of ourselves. We wanna recreate what reproduction means for ourselves, and that includes all bodies, all genders, all sexualities, classes, immigration, refugee [00:29:00] status, so on and so forth, right? So I think for me, what’s been vital to reproductive justice.

Deana: Since we’re here talking about frameworks, can you talk about using a transformative justice lens to understand and intervene on family violence and child sexual abuse?

Cara: I will offer something here is that in 2006, whatever the year was that we all sat down, right?

Again, props to Raksha for the partnership between Raksha and generationFIVE, and then the invitation for Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective, Project South, right? Georgians for Choice. There were many of us in the room, Queer Progressive Agenda, Communities United, Men Stopping Violence, I mean, so on and so forth.

There were ways that the leadership of those people, Sonali Sadequee, Steph Guilloud, Mia Mingus. Essentially, for us to come together and say, “how are we gonna hold transformative justice and community accountability [00:30:00] processes in movement, in our communities, with our families?” It was earth shattering. Like I, I do not underestimate what it is we were trying to do politically as a liberatory strategy in our movements.

It really pushed us. It pushed me, and it awakened my understanding of how to organize differently. I had been doing work as an independent healer doing healing work with community members, and what I was noting, in particular, in movement space is a lot of people were survivors of child sexual abuse. And/or of some kind of sexual abuse in their childhood or adulthood.

And there they were inside of these movement building organizations working with survivors of abuse and not having a way to manifest or wrestle with where the overlaps were with the work they were doing on the ground and being survivors [00:31:00] themselves. Right? It was still very taboo to talk about, I’m sorry, but it was still, in the early 2000’s, still taboo to talk about being survivors, period.

And I had done deep work by way of my comrade and dear friend and sister girl Aishah Shahidah Simmons, who’d been doing that work for a long time in the ‘80’s when I met her in the ‘90’s. It was not new to me, but I just wanna say for creating a space for people to understand their role in organizing and their role as survivors were… had a relationship to each other, was pivotal.

And became so integral to the ways we could imagine organizing inside of the Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative. I found it so exciting. And I do wanna say for myself as someone who’s 52 years old and watching this country go down into hell. But anyway, sorry. As.. At 52 years old watching some of the work, [00:32:00] uh, that I was a part of devolve, I guess I wanna say, you know, being out in the streets, you know, for Roe v Wade and watching that taken away. It’s awkward. t’s uncomfortable.

You know, there’s just some things that I’m amazed that are happening in this world that I’m like, really? (Laughs) But that being said, I came out of the anti-violence movement. That was my first movement organizing experience. And it was racist, it was classist, it was all the things. And it was important. It was vital to the growth of my organizing. But it didn’t allow me the opportunity to think transformatively around how we talk about people who are survivors and people who cause harm.

And for myself as a survivor of family violence who worked extensively with my father for years around him being someone who caused immense harm in our family and caused physical violence, and to watch him go through his journey. But then together, we came together and held our own accountability [00:33:00] process so that that would then impact how we could break the cycle of violence so it wouldn’t go on to the next generation in our family.

And I am forever fiercely committed to not ever putting, turning people away, putting them in jail for…because they cause harm to someone. I have always never chosen to call 911 if it meant I was gonna lose a family member. I grew up believing in that, but I didn’t understand that as a political strategy. I understood that as a survivor, you know, get it done, do what you need to do. But to not be able to bring that kind of politic into a space that…inside of movement, because it, it always reared some weird, um, just awkwardness.

For instance, losing Black feminist friends when I chose to side with my father and when I said, “oh, I think he’s transforming his role as a person who perpetrated violence.” And they said, “that’s impossible. When someone’s violent, they can’t ever change.” And I [00:34:00] was like, what? That’s my father. You better roll up your sleeves. What? So, but I’m just saying like, to understand that that was a breaking point, and that I had to align with my political values and just stand in my convictions, that absolutely not.

That’s like you saying, you’re gonna turn away substance abusers for using substance. Like what are we talking about here? Like it just felt like it just evolved into this weird binary. Be punished or punish, be a survivor and be clear of causing harm and being the one you cause harm. Right? These are obvious conversations that TJ brings.

But in the ‘90’s I wasn’t a part of those conversations. I felt very isolated and alone in movement. And so by the 2000’s when it was much more visible and oral and out there in the world, it felt so affirming and so powerful. I felt like I could fucking do anything, right? Because I was like, oh, here we are. I can bring all my shit up in the room and tell you I will protect someone who has caused harm, and I [00:35:00] will assess how I have caused harm while I am both a survivor and work with survivors. Let’s talk about it.

Mia: To kind of build off of what you shared, Cara. It’s one thing to talk about harmers and to humanize them and to talk about how, you know, no punishment, what have you.

It’s another thing to talk about harmers in relation to child sexual abuse. And we were talking about one of the most unforgivable, disgusted, you know, like one of the forms of violence that are considered just unthinkable. “Pure monsters,” have been pathologized – both survivors and harmers – pathologized into oblivion.

And I think child sexual abuse, in particular, occupies a particular place in our collective psyche, as well, that even broaching these kinds of conversations. I mean, the political and personal work [00:36:00] required to even be able to have the conversation, let alone engage in the work was tremendous.

And I think to do that in a time where, you know, in particular, in Atlanta, many, many places were facing such huge political challenges that I think it was also for us trying to figure out how do we bring people into this conversation and work when they’re facing intense state backlash, for example, right? And targeting. And what does that look like?

And so I think also in that is we were bringing a Southern political framework and a Southern political experience to not only transformative justice work, but TJ CSA work, and what that looked like. It’s like child sex abuse was and continues to be like this giant, gaping wound that exists inside of our movements that we just pretend to not see.

It’s the elephant in the room oftentimes, [00:37:00] and that people are moving around with this trauma and these experiences. And it’s not like it doesn’t follow them into their organizing, when we know the statistics and the rates of child sexual abuse, meaning anybody under 18, they’re at epidemic levels. And so I think for us to be bringing this type of, not only about the issue of child sexual abuse, but saying we don’t believe that we should be relying on the state to handle it. And we are not for the state response, which even still today as well as back then, like the majority of CSA work is work that is deeply invested in that state response and that outsources that work to the state, which then, of course, just, you know, gets further entrenched in control of populations, et cetera, et cetera, state sanctioned violence. So I just wanna name that because I feel like it was so brave of [00:38:00] us, like in terms of going to people and saying like, this is what we’re doing. And having people either be on board and say like,” oh my gosh, this is what I’ve been looking for,” or “What the fuck are you talking about? Like, are you saying that you are siding with child molesters?” You know what I mean? Like it was very intense.

There were many child sexual abuse survivors in the ATJC, myself included, and I think that in particular as well, like what that meant for all of our individual, like coming into our political identities around child sexual abuse, not just like descriptive experience.

Deana: Those are super important stories and I really appreciate you both for sharing. Now I, I want to move on to talk about successes and later some challenges because they, of course, go hand in hand. Can you both share a few success stories and what made them possible?

Cara: A success story for us, I would say, is when Kindred Collective really started [00:39:00] Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative, we got deeply involved with the Free Shifa campaign, which is a campaign led by the Sadequee family to support dropping all charges. Sonali’s brother was falsely accused of being in a terrorist sect, as a Muslim, it’s very complicated. The case was painful to witness, but in all the Islamophobic stories of it and the carceral punishing of the campaign, what I learned is that when we imagined how Kindred could support families who actually in the early 2000’s Muslim communities that were being targeted specifically in the South, especially South Asian communities, in particular, and Black Muslim, that were being targeted and being essentially associated only to as terrorists.

How do you talk about care or healing around generational trauma from Islamophobia in the South? [00:40:00] was a particular question that we as healers and health practitioners, we rolled out with the Free Shifa campaign and said, we’re here to provide care around the trauma you’ve experienced as Muslim communities in the South.

They said, are you ready to talk about torture? Are you ready to talk about the level of generational trauma from Islamophobia? Are you ready to talk about what is meant for like state surveillance and policing? And are you ready to talk about how you weren’t there for us when the mosques were getting spray painted in Atlanta during the early 2000’s as a targeted attack by white supremacists?

Like it’s not consistent. How are we gonna have a consistent conversation? Because if you’re only coming in on a campaign and you’re not gonna be there for community strategies ongoing, then we don’t wanna be a part of what you’re offering. So we had to have some real roll out deep and real conversations.

How do people who are not Muslims show up for the Muslim community? And what [00:41:00] are we willing to learn about their faith-based practices around traditions of healing and care? And I use this when I talk about healing justice as a success story to say, “you must always ask to be invited. And you must always ask for permission to work for communities.”

Don’t ever assume they need you more than you need yourself. You know what I’m saying? And so I didn’t think we rolled in with assumption. I thought we rolled in with like the best empathy political strategy. I thought it was dope. And then we got push back by elders, by youth, by people saying, “no, you weren’t here two years ago, three years ago, 10 years ago. Where you been? What you doing? How are we gonna change this dynamic? Because it feels like a savior Christian mentality. We’re not feeling it.”

And so I really had to reimagine right, again, and awaken to strategy around how do we support [00:42:00] around survivorship, around sexual abuse, around terrorism by the United States of Amerikkka. Like how are we really showing up for accountability in ways that are useful, relevant, and given consent to do it without assumption that we know what is needed?

And for me, it changed my organizing, as well, that we experience immense targeting during the support of this campaign. And we set up safety, moving people literally in the dark so that people wouldn’t be targeted by the state for trying to organize against the conviction of Shifa. And people’s risk level was incredibly high. And for me, as a non-Muslim organizer, spiritual person, understanding how my home needed to be open and available. And what did that mean to create safety for other faith-based communities? Specifically Muslim communities in the South at a heightened time of [00:43:00] surveillance and violence by the state.

So it really opened my eyes to, oh, okay, let’s see what it means to provide care under surveillance. What it means that care is not inseparable from safety. This is, they must be part of the same.

Mia: I feel like one of the biggest successes that we’ve had, we had a lot, but I also feel like in addition to the Free Shifa campaign, like, I think our collective and collaborative fundraising was a huge success because that was at a time where people really weren’t doing that. We were doing that in a grassroots level in terms of like fundraising, and it was amazing because, well, one, we were, we were having fundraisers for the three organizations together, Project South, Kindred and SPARK.

And through doing that work, it was such an opportunity to educate all of our different communities, our respective folks, right, around why we are collaborating with these other groups, [00:44:00] and why they are critical to our collective survival. And that interdependence was such a key part of that. And we were talking to our reproductive justice folks and saying, “this is why healing justice is so critical to reproductive justice. This is why ending genocide and poverty and the work that Project South does around racial justice and Southern movement building and Southern leadership build….This is why it’s so critical.” And that wasn’t happening in that many places at that time, in a, for lack of a better term, like formal way, you know what I mean?

People have always been working together collaboratively, but like we were applying for grants and trying to get funding to help with some of our projects that we wanted to build and funders straight up didn’t understand it. They were just like, we don’t understand why you’re applying together. And I think that kind of framework of saying, well, at least for me, Cara, was also informed by a [00:45:00] Southern political framework of interdependence. But also beyond just like, interdependence, I feel like it was about having an investment in shared leadership and work that was informed by a Southern political framework, right? That, of course, was informed by the scarcity of resources for the South, which continues today. That it was informed by the desire and the need. So it wasn’t just the need, it was also the desire for an interdependent approach to resourcing the work that is grounded in relationship and grounded in an interdependent, and grounded in relationship, understanding of leadership. That we were saying to our folks and to funders, like, we don’t exist without Kindred. For us to exist and be, well, we need Kindred to exist and be well. We need Project South, we need, you know, like all these other groups. And I think that that was a success.

We did that twice. I mean, in terms of the grassroots fundraising, and I feel like that was something [00:46:00] that a lot of our folks hadn’t seen. I know it’s like, what a concept, “sharing,” but that, that it was saying, you know, we’re not just gonna fight over the few resources that exist. Like that’s bullshit.

You’re gonna fund us all or none of us, you know, because we don’t want stars. We want constellations.

Deana: Yeah, there’s so many resources out there and they need to be given to all of our people. So let’s talk challenges. What were some of the challenges that you wanna share that really stuck out to you, and how did those challenges grow your work?

Cara: People just didn’t get it. Not only, as Mia said, they were already underfunding the South, but they just assumed organizations on the coastal, you know, Bay Area or New York, should be running our strategies or at least be funded to run them. And that was just a disappointment. But that caused tension and distrust.

Where people in the South, in particular, in Atlanta, [00:47:00] Georgia, who may have started on the ATJC, said, “wait a minute, we don’t want to play with a national organization or a national campaign on this. If we’re not doing it ourselves, then we don’t want to be a part of this at all.”

Mia: I think the national versus local was a huge, huge challenge.

And, you know, I think another big tension and big challenge just consistently is sustainability of the work and resourcing the work. And I feel like really the only reason we were able to last as long as we did was because we had three people who were in leadership in their organizations who could say and make the decision, right? And say, this is a part of our work. So like, in a sense, like our time is being compensated. It is more sustainable and who are able to move some of our organization’s resources and time to this [00:48:00] work. The collaborative fundraising that I was just talking about, it was also like, that was SPARK’s main big fundraiser of the year.

And, you know, and that was a decision because we had people, members who were in positions of power in the organization. I was able to say, this is the fundraiser we’re gonna do like as our fundraiser. And so I think that also was why we were able to exist, but also was its, was its own challenge, as well.

Because for example, we wanted to do a collection of Southern digital stories of Southern stories around child sexual abuse that were digital stories based in the South. And we tried and tried and tried to get funding for it. It wasn’t even that much money in the scheme of things. We could not do it.

They, they would not fund us to do that. And I think this is something that still persists within TJ work. Like how do we resource the work? There are some groups who are able to get some resources, but, [00:49:00] in a large part, most people are donating their time and just doing it at night, on the weekends, what have you, which is wonderful. And, and I’ve been part of many of those types of groups, as well. And so I think there’s pros and cons on both side and both. And, it’s like, you know, at a certain point, you’re like, it really limits who can be a part of that work. It limits how much work you can actually get done. And so it was this delicate balance of sustainability.

And then also, let’s just be real, like the emotional toll that this work takes, not everybody has or wants to do. And that, and I completely respect it, like, I get it. Like and people…you know, people have kids, people have other jobs, they got family, extended family who, whatever they need, partners. And so that has always been like, in terms of just the broader sustainability challenge, it’s always been that way.

And Atlanta is a transient city, and it’s [00:50:00] a big city. And so people move in, they move out. And so I think that was also, it’s always been a struggle. Yeah. So I would say, I think sustainability just at large has been, or was, I should say, a big challenge.

Cara: Yes, I love it. The only other piece I would add is that we were trying to do study and practice at the same time.

So not only did we have all the conditions that we were all responding to, you know, outside of ATJC or as a part of ATJC and our political organizing work, but we were actually trying to do deep study on what interventions, if you will, could look like. What strategies, rolling out strategies around CSA and TJ could look like. TJ and the community accountability specific to different instances of harms, abuse and violence. So people were running at different levels, different risk assessments of the work they were doing. [00:51:00] Kindred was holding, uh, really we only held in the end maybe three or four, community accountability interventions.

Then the third part, study practice tools. Offering tools to people who wanted to hold their own, some people use the language family intervention, and we supported them on risk assessment. And then we realized this is ongoing, right? Like there was one person in a highly volatile situation, in a refugee family, couldn’t afford absolutely not to lose any relatives to the state and absolutely feared for their lives if they came out as a CSA survivor.

And so we said, “oh, what can we do to support?” And she was like, “well, how long are you here for? This could take years.” You know, and that’s, that’s real, right? That’s what we know. This is based on relationships, based on how much risk you’re, you can take at any given time and what the situation is on [00:52:00] conditions of survival.

So having to pace it out. I think some of us, for myself, understanding what are we asking people to do was tremendously challenging. Some people in the end, offended is a big word, but I felt like some people felt a little insulted where they’re like, “well, if you can’t help me ongoing, then what is the point?” You know?

And I was like, well, that’s the thing. We’re building study, we’re building practice, we’re trying to build this as, as we’re, we’re moving through it. So I don’t know how long. Some of us will have to take a step back. Some of us will have to move forward. It… the, the formation is gonna change. If that feels disruptive to you, disrespectful, distrusting, then we can’t offer the kind of stability you might need. ‘Cause the person you’re looking at now might not be here in a year. Right? Because we did have a lot of, um, turnover to everything Mia just named, people’s lives. That was definitely a challenge on how you actually hold [00:53:00] practice and study together in intentional ways and how you really roll things out to a completion, or at least to a place that feels, “success” is a funny word, feels “held” for the people that are involved in the process.

Mia: I feel like it’s implied in what Cara is saying. I just wanna pull it out explicitly like the, the challenge of mandated reporting around child sexual abuse in particular. Like, I mean, you know, people doing adult on adult violence, it’s, it’s not like there’s no challenges there, but it’s a uniquely different. Like CSA, because there are minors involved, and, and also because child sexual abuse continues to be such a successful wedge issue, particularly around carceral, everything. And so constantly gets brought up to argue for harsher sentences, more prisons, more cops. And so the fear that people have, rightfully [00:54:00] so, around anything related to responding to child sex abuse is very, very real.

And having to think through mandated reporting, you know, on top of everything else that you or your family might be facing. It’s a very real thing.

Cara: Kindred got also got involved in working with folk people that were wrestling with the prosecution of a family member for causing harm or abuse and how, how should they be punished?

Right? So like the disbelief that there’s another way to do it outside of state apparatus, and how will I take care of my family that just lost a family member to the prison, or the system, and how the family can wrestle with the possibility of either that that person shouldn’t have been incarcerated and what, how will you have them reenter your family?

Just sort of expanding what TJ and community accountability really look like in real time. We were holding CSA and we were holding some people’s processes around how to struggle and [00:55:00] wrestle with carceral state, and reimagine not wanting to punish a family member while trying to hold your family together when immense violence has happened. And not inviting the state to get involved.

Like this was just so much out of the realm of what people could imagine was possible. Sometimes there was absolute rage towards us ’cause they were like, what are you doing? If you can’t promise something solid, then what’s the point? What truly is abolition? I we think that you’re, you’re dangerous.

And that was the beginning of the practice, right? That’s the ongoing struggle is understanding how we build trust and relationships that feel that we can go through the ebbs and flows of it because there is no concrete one way to get it done and to do it. And some people needed that structure. They’re like, sorry ma’am, but no.

Deana: I keep saying this, but I really do appreciate the stories that you’re sharing. They are amazing. [00:56:00] And I know a lot of people are gonna listen and learn and have a better understanding of not only the successes that you experience, but also the challenges. And so I also wanna ask you, for the new people who are coming up in this work, what do you want new organizers to know?

Mia: I mean the first thing that comes to mind honestly is that the work is slow. And I feel like a lot of people come to this work wanting it [snaps fingers] right now. You know, like, I want you to give me a weekend training and then I’m gonna go and do transformative justice and it’s gonna be great. And it’s like, well, I mean you could go and do it, but like the work itself takes time.

But also it takes time to build up your own capacity, like your own learning. Listen, I say this all the time, but there’s no substitute for time in. The practice is what is most important, and that takes time. And so if you’re not in it [00:57:00] to actually practice this work, then there’s plenty of people who know a lot of things about TJ, but they’re not practicing it. And practice yields the sharpest analysis.

You could be really smart. But once you put the pedal to the metal, then you really find out, oh, these are the things that work. Oh, these are the things that we need to go back and work on. Okay. And then you keep tweaking and tweaking and that’s the key. And so I would say take the time.

Take the time to build up your own skills, to build up your own knowledge and capacity, and also let the work take the time it needs. Because accountability processes are not one and done. I mean, they’re, some of them last years and years, and I hear Shannon Perez-Darby in my head all the time, like “right size our expectations.”

Cara: This is where I’m at right now, right Is um, just coming off of writing this book about healing justice, which really elevates the [00:58:00] relationship to transformative justice and the learnings of transformative justice and an abolitionist lens on care and healing, is just wondering real baseline, y’all, basic tools. What is safety outside of the state? Like not having that conversation with your family, your community, your chosen family, birth family, your people, even in movement, like for us to assume that we know that we’re already aligned, lies! We are not. So can we at least have a baseline conversation? What is safety outside of state and what does it mean to have a creative community led by us / for us. Let’s start there. What is care and healing outside of state? And what do we need it to look like, where it values and is… brings dignity and respect for how we wanna be treated and cared for? These conversations, really baseline. But I’m recognizing a lot of people have never had the opportunity to have them.

And I do think [00:59:00] it is a practice that many of us do. We just do it organically. But let’s offer that as a political cultural strategy for people to just roll out for whenever they need to do it, or are willing to take the risk to do it with their people. Right? And then this piece around Atlanta Transformative Justice Collaborative, and really we went from 12 to four. Okay?

Like, don’t be surprised when people will need to leave. Well, they’ll need to go because the work is hard or things come up in life. Or maybe they’re just not aligned with the political values and strategies that you’re trying to roll out. Like there’s gonna be difference, right? I don’t think there’s one model, there’s gonna be struggle.

We challenged each other. Shit got hard. Most importantly though, what we could always come back to is, what are we trying? And to be able to debrief with each other. A lot of, Mia, what you just offered right, is like, it takes a long, slow journey and it helps to have [01:00:00] people along the way to… checks and balances. Am I doing this well? Is this working? Am I imposing my own trauma on these people? Like really just trying to assess what your role is and staying relevant and sharp to the, to the situation is critical. And to have people that you trust, love, and respect, who understand the conditions you’re working inside of. It keeps you humble, but it’s also necessary, I think, for the practice.

Mia: So I say this all the time, which is why I named SOIL, SOIL. That is we need to build our soil and that we need to stop trying to plant plants in toxic or barren soils, and expecting them to grow and thrive like they would in rich, fertile soil.

So because, you know, TJ is not just about the incident of what… the harm or the violence that happened. TJ is about connecting the incidences with the conditions that created or [01:01:00] allowed for that harm to happen in the first place. Which is why when we respond in a transformative justice way, we’re saying, how do we respond to this incident, right? In a way that shifts the conditions and transforms the conditions that allowed for it to happen in the first place, so that it doesn’t happen again. And focus on your conditions. Look at what your soil is. And take the time to build up your soil and like. Don’t just look at the plant. It could take you years to build up your soil.

You know, I think about the, the metaphor of like the person who plants a pepper plant and maybe that first year it only yields like one or two peppers. Then you harvest those peppers, you get, you harvest those seeds, you plant them the next year, maybe the next year you get 10. Maybe the next year you get… and that is what we’re trying to get to.

And so I would say, look at your conditions. And I don’t just mean your individual conditions, although like I talked about in the first part of this, that’s [01:02:00] part of it too. I mean, the collective conditions you’re in. You know what I mean? Like, so if you are in a community and they don’t have any access to healing, individual or collective healing, they don’t have access to food…healthy, you know, and, and clean water. Like just understand what your soil is and what your conditions are that you’re operating in, and do work to shift those because that’s part of transformative justice work as well. That it’s not only about these incidences of harm, it’s not only about, you know, domestic violence, sexual assault. Yes, those are absolutely critical and core to TJ ’cause it was one of the main reasons why TJ was created really, but also are things like farmers and being able to have people be fed, have affordable housing, have access to relationship and community. All of these pieces are part of the puzzle that we need because we can’t run [01:03:00] successful interventions or TJ processes if we’re in terrible, hostile conditions.

If you are in a community where punishment is, is all the rage, and that’s all, that’s the toxic part of the toxicity in your soil, then do the work to detoxify that soil. Instead of dropping even skilled organizers, TJ practitioners into something, trying to run a process and then being like, a’oh, TJ doesn’t work!” And it’s like we need both of those things to happen at the same time.

Deana: Thanks to the amazing organizers that live and work in Atlanta who are making this world a better place for all of us every single day. As always, I encourage you to take the lessons you learned today and keep practicing. Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies?

We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions, and Just Practice Collaborative want to share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal [01:04:00] violence without the use of police or carceral systems. Find the link in our show notes to learn more. Stories for Power is presented by Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative, executive produced by Mimi Kim, Shira Hassan, and Rachel Caidor.

Produced by Emergence Media. Audio editing and mixing by Joe Namy and iLL Weaver. Music composed by Scale Hands and L05 of Complex Movements in collaboration with Ahya Simone. Stay tuned for more episodes of the Stories For Power Podcast. Check out our show notes and go to StoriesforPower.org to learn more.