[00:00:00]

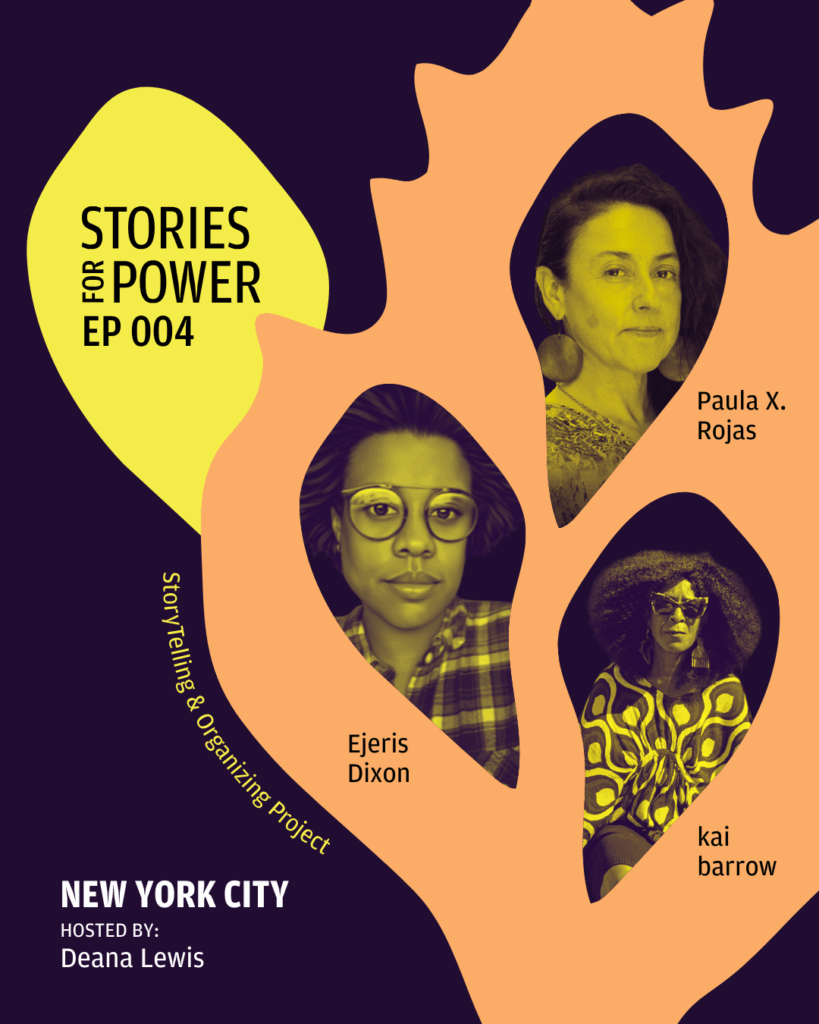

Deana: Welcome to Stories for Power. I’m Deana Lewis and I’m a member of Just Practice Collaborative. Stories For Power is an oral history project produced by Just Practice Collaborative and Creative Interventions. It explores the political lineage and historical experiments that gave way to this wave of transformative justice, community accountability, and prison abolition.

In each episode of Stories for Power, we speak with activists and organizers from different cities who were, and continue to be at the forefront of feminist abolitionist praxis. They talk about the bold experiments and interventions they were a part of in the early two thousands through 2010 and how their work informed abolitionist transformative justice and community accountability organizing today.

Don’t worry, if any terms or words have you confused. We’ll do our best to link to [00:01:00] resources in the show notes, and you can always go back to listen to the special introduction episode for more context.

In this episode, you’ll hear from three inspiring abolitionist feminists, kai barrow, Paula Rojas, and Ejeris Dixon.

We will talk about the courageous and radical work they were a part of in New York City between the early 2000s and 2010. Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems.

Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

A note for our listeners, we’ll be discussing violence, including police violence, intimate partner violence, and community violence. We encourage you to take care of yourself, and we understand that taking care of yourself can also look like not listening to this [00:02:00] podcast until you’re ready.

Now let me introduce our guests. They have amazing and extensive experiences and knowledge. I’ll do my best to summarize. We have linked their full bios in the show notes. You can also learn more on our website StoriesforPower.org.

kai barrow is a visual artist who lives and works in New Orleans. Interested in the praxis of radical imagination, her sprawling paintings, installations and sculptures experiment with abolition as an artistic vernacular.

kai: I’m kai lumumba barrow. In early 2000s… I’ll start with SLAM: Student Liberation Action Movement. And that moved from there to LaGuardia Community College where I got to work with Janet Cyril and Critical Resistance, the bulk of my work in that, in that timeline.

And during that time, we were doing a lot of work around political [00:03:00] prisoners, the ideas of prison industrial complex abolition, and then tying that to also police violence and stopping police violence in New York.

Deana: Ejeris Dixon is an organizer and political strategist with 20 years of experience working in LGBTQ anti-violence, economic and racial justice movements.

They’re the former executive director of Vision Change Win Consulting. There they partnered with organizations throughout the United States and internationally to build their capacity and deepen the impact of their organizing strategies. Ejeris previously worked with the New York City Anti-Violence Project as a Deputy Director and as the founding program coordinator of the Safe Outside the System Collective at the Audre Lorde Project.

They’re a co-editor of Beyond Survival: Stories and Strategies of the Transformative Justice Movement with Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, which became a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in LGBTQ [00:04:00] Anthology.

Ejeris: I’m Ejeris Dixon, and I started off as an organizer in New York City, mostly working on workers’ rights campaigns and I worked at an organization called Community Voices Heard.

I organized childcare workers at an organization called Families United for Racial and Economic Equality. And I think actually that’s when I, I met Paula then. And I started to meet kai around that time, um, through Critical Resistance, New York.

And then at that point, a friend, a dear friend, Ann Chadwin, recruited me to work at the Audre Lorde Project. And the Audre Lorde Project had been doing a lot of police violence work as it affected queer and trans communities of color. And also many of the members of the community were also experiencing homophobic and transphobic violence. So the goal was to address all the forms of violence that were happening against our communities without relying on police or prisons. And I really took a lot of inspiration from Paula’s work and [00:05:00] kai’s work, and am so grateful to be in community with all of you.

Deana: Paula Rojas is a Chilean born community organizer, licensed midwife, and social justice trainer. She grew up in Houston and followed in the footsteps of family members in Chile and began working on social justice issues affecting her local community as a teen. For the last 30 years, she has organized at the intersections of class, race and gender to build collective people power in her local community as she was experimenting with different forms of grassroots organizations.

She co-founded various community-based organizations including Sista II Sista, which you will hear about in this episode. Over the last 15 years in Texas, she has supported the training and development of community organizers and their organizations working on a range of social justice issues.

As a midwife, Paula developed a model to practice a vision for a just and loving approach to pregnancy, birth, and new parenthood for poor and working class BIPOC families. She is the [00:06:00] mother of two amazing kids, Xue-li and Camino, and loves to dance.

Paula: My name is Paula Rojas, and I was working in New York as a youth organizer. And that started in 1995 working at a community organization called El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice.

And from there, a grouping of us created this collective of young women of color that was called Sista II Sista. And from there I kind of, over time moved into this work. It wasn’t what we planned, but the experiences of the work that we were doing, the organizing that we were doing, led us to first challenge the police state and then think about moving beyond it.

Deana: Thank you so much for those intros. Now we want our listeners to get an idea of what New York City was like at the time you were with those projects. Can you talk about the historical context a bit for your communities at the time? [00:07:00]

kai: It is so funny, these intersections. I was on the first board of Sista II Sista with Paula and others.

I remember Community Voices Heard. There was just so many grassroots organizations that in the late 90s, I think were getting politicized around the prevailing overwhelming violence that was coming out of the New York City Police Department and being directed mostly at Black and Brown bodies. So we saw a lot of like just back to back police murders from Amadou Diallo to Patrick Dorismond to Malcolm Ferguson.

So these were like… you know how it feels when we witnessed police murders, so our city was being under attack and a lot of the youth and people who were directly impacted by that violence started looking [00:08:00] at points for coalition building, community organizing, and cross borough organizing. We started to build, I think a, not just a grouping of different organizations, but actually a culture of fight back that included a lot of us going on delegations to Chiapas and Brazil and Argentina, and looking at some of the struggles that were happening globally while we continued to bring the skills and ideas into our local organizing.

So I think horizontalism, for example, had a big impact on some of the organizing that SLAM: Student Liberation Action Movement, Critical Resistance, Sista II Sista, FIERCE, which was another organization that I got to be on the first board of which was a group of queer youth and eventually became queer youth of color, who were doing a lot of organizing around, um, [00:09:00] public space and safety for queer youth at the piers. Also Queers for Economic Justice, QEJ was emerging, so there was a lot of shifting of power, or fighting power directly.

And I think we all were in some way or shape or form in dialogue with each other, either in terms of mobilizing each other, or sharing resources and knowledges. There’s more, but I’ll stop there. That’s one way I wanna paint the, the picture of the community at that time.

Paula: The picture you painted, kai, was beautiful and very complete and colorful.

So I, I think what I would add to all of the things that you’re saying is parallel to all of that, we were also in a period in New York of really aggressive advances, right, in gentrification and kind of economic displacement of communities. And I would say [00:10:00] those were intersecting with how policing was used as an arm, you know, to kind of clear the path for luxury condos and, you know, fancy restaurants in our neighborhoods.

I think that impacted our visions, our questions, you know, in a way that brought many of us to really think more critically about capitalism. Those of us, many who were doing racial justice kind of community-based organizing really started to make these links between white supremacy and capitalism in our work.

And for us at Sista II Sista, like what you’re saying, kai, it really made us reach for a internationalist perspective to further understand what’s happening in the belly of the beast, right, in, in New York City in relation to the rest of the world. And so we also were very much looking to be nourished from what was happening [00:11:00] outside the US, and staying very focused on what was happening in our neighborhoods is part of what I think the…was special and magic about that time.

The other thing is what you said, kai, how we were doing cross borough kind of work. So we were very much in one neighborhood within Brooklyn, but we were working with folks who were in the Bronx, others were in Queens, others were in other neighborhoods in Brooklyn, right? But still staying very hyper local in our work and understanding the value of doing work that is, you know, building with our neighbors, going door to door, block by block, you know, was, was part of the way that we were approaching our work, that I think is also very powerful of how we were doing it at the time.

And then the other thing I would add is for people like me, I was a, I was a young organizer, you know, I was part of a crew of people, maybe 18 to early 20s. That’s how we were at Sista II Sista. We were very [00:12:00] much kind of inspired by generation above us. By you, kai, by the folks.. We looked for people like you, Iris Morales, ex Young Lord, right? And others who were intentional kind of tias, you know, that we were asking for support from.

For me, I was working at El Puente that came out of some ex Young Lords, but they were men, you know, who didn’t have all the perspective and experiences and analysis and critiques that you kai, and Iris [Morales], and Eugenia [Acuña], Joeritta [Jones] and others had.

And that’s why we kind of, you know, reached for y’all to help us build, uh, very intentionally. And it really made us feel like we were part of something. We were building on something before. We also had, remember at the time an ex Black Panther who was running for city council, right? We had Richie Perez, who has passed, as a Young Lord who was doing work against police [00:13:00] brutality with, uh, a National Congress of Puerto Rican Rights.

Right? So we had these bridge people like y’all that were kind of, that we were holding onto as we were thinking about what we were building as young people organizing. And so it was, it was youth specific, and yet it was intergenerational with a lot of intention.

Ejeris: I think the organizing that I first entered into was also in the aftermath of like kind of the quote unquote ” welfare reforms”.

So people were being pushed off their benefits. Crew of city workers had been like unionized working class people had been laid off so that people who were on public assistance were then doing work in the parks, doing work that was sanitation for their welfare benefits. We were impacted by the Iraq war and the mobilizing we were doing against the war.

I think that we were also a post 9/11 New York, but fairly recently. So the increased militarization of the NYPD, that being held up as like [00:14:00] kind of a, a beacon to other parts of the country. But also like the NYPD, like kind of highlighting really repressive tactics showing other parts of the world how to oppress people in New York City as, as an example.

And I just have really visceral memories of Operation Impact, like the way that there were just like so many rookie cops, block by block by block. Where our neighborhoods felt occupied all the time and every day. So if we have a context of opposition, there’s also like, the context of resistance that Paula and kai have been talking about.

And so I, I remember a lot of the multi-issue organizing we did around when the Republican Convention came to New York in 2004. And I remember the mobilizing we did around the attack of Critical Resistance, New York City. Like there were just so many different ways that we were, we were coming together.

And, and through that there were also murders of queer and trans people. There was the murder of Rashawn [00:15:00] Brazell. There was the murder of Sakia Gunn who was in New Jersey. So we also were just trying to build the resistance we needed to live and to be in liberation movements.

Deana: Thank you for that. What I love hearing about is how the organization Critical Resistance is such a thread through all of this work.

So what else kicked off your work? What else were you responding to?

kai: Critical resistance across the board had, um, a theory of change that emphasizes dismantle, change, build as a framework for how we, you know, create a world without the need for prisons and policing, et cetera. So in that context, one of the things that the New York City organizers wanted to really see is how do we construct these alternative models, right? And I think that a lot of the folks that we were in partnership with, like the people. In this, uh, [00:16:00] conversation, and many others were also interested in that idea of alternative models. Like, so how do you create these kind of liminal spaces?

What, how can you construct the world that you want to live in, you know, while you’re making that world? Right? And so I think that was a draw for us. There were a lot of us who, obviously doing policy work is relevant and important, but I think at that time the folks in New York City were interested in, um, trying to pilot some models.

And again, like Paula said, we had the privilege of being a space where we had a lot of international influences and access. And also we had about three generations of organizers who could give us direction, input, this is what we did, you know, from folks like Herman Ferguson and Yuri Kochiyama, to folks like, you know, whatever, [00:17:00] I don’t wanna name drop, but we had a range of people, you know, who were in their late 80s and 90s, to people who were in their early or mid-teens sitting together and engaging these ideas.

Yeah, I think that need for an alternative model drove our work.

Paula: I was a part of a crew, kind of a, a peer group of people who were looking to do community-based organizing, but with kind of a radical social justice perspective. And I was at El Puente as a youth organizer. And the things that really I felt challenged by was that it was very hierarchical. It was very male led, you know? And there was the people at the top, and the people like me, who you know, would make $20,000 and work seven days a week and love every minute of it, right? But we started to bring a critique, a gendered critique to the work, and that’s when we went off, spun off and [00:18:00] created Sista II Sista. And I just wanna give mention, I was a worker at El Puente and recruited into this conversation that was actually started by the Black Student Leadership Network and the Universal Zulu Nation to create Sista II Sista. And Nicole Burrows, who I thought should be on this podcast, was the one that recruited me in.

And so what we were doing is Freedom Schools for young women of color. That’s what we called it at the time for like 12 to 17, 18 year olds. And we weren’t intentionally working on police issues. We were doing kind of what in community organizing, we call it kind of pure base building, membership building, political education. To build enough of a mass of younger women to do issue development together, right, to collectively decide what are we gonna work on. So we did that for a few years before we ever decided what to work on, and as we were trying to figure out the process to kind of identify what are the issues that are affecting us [00:19:00] most…Boom, you know, shit starts happening, right? Um, someone in one of the Freedom Schools, her friend got shot by an off-duty cop on the stoop of her house when she was 15 years old, you know, having an argument with her mother and an off-duty cop shot her. At the same time as we were trying to figure out issue development.

And all the context that kai and Ejeris said, the day to day of how that kind of militarized police feeling on the street in our neighborhood. What was included in that was sexual harassment by cops to us and younger women. Right? In this very weird kind of way where you don’t know if they’re kicking it to you, or if they’re using the police authority to ask you for your phone number, where do you live? This kind of stuff happening on the daily, every day, on the way to school, after school, to almost everyone. And so [00:20:00] for us it was looking and doing kind of a popular education process of like, once that happened, the dramatic, the shooting kicked off for everyone. Like, “wait a minute, “this happened to me,” “this happened to me”, “this happened to me,” “this is happening to me,” “this is happening to me.” And us, who were the older young women, you know, we were the adults, you know, the same thing had hap… was happening to us, or had happened to us. And I know for me, when I was 17, the first time I was sexually assaulted was by a cop, you know?

Um, so it, we were all living that. And I think that’s what turned us to say, this is the issue we need to work on. And the other part that I didn’t mention before was kind of the transition between pre 9/11 and post 9/11. Right? I would say before 9/11, because of a lot of work that others had done already in New York, that we then were a part of, I would say in the general sense, most people in New York thought critically, or a lot of people thought critically about the cops and [00:21:00] knew that the cops were fucked up. Right?

And there was a general on the street feeling. I, we know that the cops are not our friends, right? Then we were doing this work and then 9/11 hits, boom, from one day to the next. Nobody thinks the cops are fucked up, or if they do, they’re not gonna say it right? All of a sudden, cops, firefighters are like heroes on pedestals, shrines, right? That everybody is like talking about celebrating.

And I think that really pushed our work backwards. I would say for us in our neighborhood work, like we had done work in the neighborhood, you know, talking to families on the blocks, getting people to think with us about why is it that these people that are supposed to protect us are actually harming us, right?

And hurting us and harassing us and harassing everyone’s daughter. People were with us. And then I think people started to kind of recoil away from us [00:22:00] after 9/11 in a way that meant we had to rethink how we did the work, how we built with our local community neighbors, right? That weren’t our members, but the other people in the neighborhood.

Ejeris: I think there’s also a piece around queer and trans movements and how they responded to violence. So I think there was a pretty big split between like, a group like FIERCE or ALP who had a very explicit analysis around policing, and analysis around abolition. And then there were like, kind of, the LGBT anti-violence groups who didn’t work on policing, who worked on homophobic and transphobic violence and intimate partner violence, but all police based.

One of the things that really kicked off some of ALP’s work was like we had multiple situations of folks who were attacked in the neighborhood, experienced homophobic or transphobic attacks. Sometimes tried to report, got attacked again by the police, and it was this place and this need to create a space, [00:23:00] similar to what Paula was saying around like what’s the intersection of a gender analysis around policing? What’s the intersection of an analysis around kind of queer and trans liberation and policing explicitly because I think there was a way that queer folks, queer and trans folks have been at the forefront of so many movements, but sometimes our own safety doesn’t get integrated in the same ways.

So it was this piece for like ALP to think like, we’ve been in the Coalition against Police Brutality. We’ve been leading police violence movements in New York City for so long. And we, we actually need to build more of an internal response and campaign where we wanted to create safety, not just for us, but for everyone, but in a way that our communities were a part of it and centered and, and not not having to hide or be on the back burner in those ways.

Deana: Yeah. Thank you for bringing up how we build safety in our communities. And kai, before we move on, can you talk more about Harm-Free Zones?

kai: Critical Resistance [00:24:00] had a party and the party was to raise money for the anarchist queer people of color… something, something. We had a really provocative flyer, uh, out there that said, I think it said “fight for your right to tear down the PIC,” or something. It was, I’m sure it was provocative, right? We liked, we liked to provoke. Right? And somebody in a keffiyeh.

And this is like 2004. The police, the 77th Precinct, raided our office, raided the party, tear gassed our folks, our members, and others who were at the party. It ended up with seven people being locked up and they became like the Brooklyn Seven, and we decided we were gonna fight back.

And in order to fight back, we wanted to get rid of the 77th Precinct. That campaign evolved into creating a [00:25:00] Harm-Free Zone, because we had to answer the question, if we don’t have a 77th Precinct, how are we gonna be safe in our communities? Right? So it required us to build in the 77th Precinct neighborhood, mobilize enough folks to make that demand.

And we found that we were not able to do that, right? For a number of reasons. One, our office was in the midst of Atlantic Avenue, which was in the midst of being gentrified, again. So Michael Radner and that Jay-Z character decided to build the Nets stadium and in that sense ended up displacing thousands of people in the community. Mostly Puerto Rican and Caribbean community folks.

So those folks who were left in the community were, um, either gentrifiers, new lawyers, mostly white folks, and young white folks who were coming [00:26:00] into Crown Heights. Fort Greene and Crown Heights is where we were in the kind of intersections of. So we found that we weren’t able to organize that community… couldn’t keep up with the community.

Community was being dislocated and moved. And, we were working during daytime hours, also during nighttime hours, but we were missing people because people who were in the community were at work, while we were trying to organize. Like if we’d have interns, summer interns, door knocking, nobody’s home ’cause they’re at work.

And then third, we didn’t live there. It was an office there. And so we had no long history in the neighborhood, right? We had no years in the neighborhood. We had no roots in the neighborhood. So we saw that we were not gonna be effective in building that kind of community. Right?

So we started looking at, going back to the drawing board and looking at, well, what does, like Paula said, like what does community actually [00:27:00] mean? And where are we able to build community? And we found that we were in alignment with a lot of organizers. That citywide organizing and the national organizing was our strength. And that’s where we were gonna build the first level of community to share like principles and ideas and values and models.

And so like just trying to lay down infrastructure for what Harm-Free Zones could be, and what we were challenged by in our capacity to produce it. That’s when we started working with the Youth Ministries. We worked with, um, May First Media.

So we had this cross sector group of folks from folks who were doing movement technology, to folks who were doing policy work, to folks who were doing community organizing, to folks who were involved in the arts to [00:28:00] come together and think through what would be a framework for a Harm-Free Zone. And then we started putting that on the ground in Durham, North Carolina, in New Orleans, and in Berkeley with differing responses.

I think the experiment is still, you know, yet to be realized because there’s so many moving parts, and one of the largest moving parts is community dislocation.

Deana: Yeah, people talk about Harm-Free Zones a lot, and very rarely do we get to hear what it was like to build them up. So thanks for breaking that down.

And the next question really kind of speaks to these different ideas of challenges and successes. Can you each describe moments or events that stick out to you as challenges or successes or something in between?

Ejeris: The work that Sista II Sista did with Sistas Liberated Ground. The work that Critical Resistance New York did [00:29:00] with the Harm-Free Zone, the work that Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice did – they also had like a zone, so. We got to inherit that, I got to come after that and see what was happening and kind of think about that.

And that, I think framed like, so one of the kind of success and challenges we had, where there’s not one neighborhood of queer and trans people of color in New York City, there were a lot of queer and trans people of color in central Brooklyn, but there’s also like other people of color who also need help, also need safety. But then there’s just this, this piece around like, so who is our community and what does that look like if we’re trying to do something that is based in a location? Because we were really interested in doing something in a location, and so for us it meant…It meant doing a lot of outreach and it meant doing kind of like abolitionist explicit outreach and facing like homophobia and transphobia like on the doors. So literally door knocking around addressing policing.

So some of our successes were just, [00:30:00] how do you talk about transformative justice, community accountability, abolition, like how do you have those everyday conversations? And so that’s why we used the term “community safety,” ’cause it was more digestible to people. We were just like, “the community keeps us safe – together.” You know? It was an easier way to have the conversation.

So, I mean, some of our successes were that we ended up organizing the mix of like, nonprofits and businesses in central Brooklyn to agree to be a part of the safe neighborhood campaign, to agree to call on each other for issues of violence and safety. We used trainings that we had learned already for marshaling and security, and we practiced them out on the street, and kind of trained each of these different safe spaces up. It was like half training, half group visioning on like, “okay, what would you do? What would you normally do if there was a fight? What would you think about?” You know? And sometimes it was like, “okay, “maybe not… maybe not the machete, but maybe this” or… [00:31:00] and so I feel like that was a success.

There was a piece that was also tactical and strategic, and I think different than what people would do today. Most of the folks we talked to overwhelmingly were, “I don’t know about your lifestyle, but I don’t think people should be killed.” Like that was kind of where, where folks were at, right? And we had to take them there. Right? And then you move from that place, like, so if we had only recruited in folks who were like, unapologetically supportive, we would’ve had a really small base of support.

So part of what we…we did was say, Okay, we’ll start. We’ll start there and after years, one of my favorite moments is in 2008 we did… we would do these annual summits, like a day of political education for the community, and we had 200 folks show up who did training on verbal de-escalation and self-defense.

There was a special meeting of all the safe spaces where [00:32:00] they came together. We had an art and culture committee, and we had a step team that performed. Like we just had really built something that felt like, felt like the whole neighborhood was able to be involved, and people were able to kind of share how they were navigating being safe spaces.

And we said the only… the line that we most want is that we are trying to build safety ourselves. Like you know your space, you know what it looks like. And so people were sharing strategies. So I think, there is this piece now, when people talk about building alternatives, transformative justice, community accountability, they mostly these days talk about processes, right?

And they don’t necessarily talk about the organizing. And you know, similarly, we got a lot of shit that it wasn’t organizing. And I tried to be like, “I’ve been in so many organ… you gonna tell me we don’t… “ Like: people coming together towards a goal, you know, making change. I think it’s the same thing, [00:33:00] but I, I do wanna say that like there are kind of transformative justice or community safety organizing projects.

Like all three of us are in that legacy. And I think it’s important to name, ’cause right now when people think about abolitionist organizing, it’s usually just concretized as like defund fights, which are still, you know, policy based organizing and not necessarily thinking about the work that, the legacy of building alternatives, and the legacy of everyday people coming together out of necessity to build safety.

Paula: For us at Sista II Sista, what I would say is a, our biggest success is that when we started this, right? When we, first we did this holistic political education, then we sped to issue development to say, “THIS is the problem that is affecting our lives collectively, that we wanna tackle together.”

And at first we were doing kind of anti- police work, you know, challenging our local precinct, right, as the problem. Doing street actions, you [00:34:00] know, film screenings outside the precinct, you know, with like sheets, to critique the precinct that showed interviews with people talking about what is the police doing for you or not for you, you know, doing all of this.

But it was still targeting the police as something that we could somehow make better. Right? That was our iterative kind of thinking in it. We were doing organizing, we were trying to build power. So who’s the target here? You know, what are the demands? And we tried some of that, and we realized, nah, there’s no demands here.

You know, there’s nothing they could do to make things better at the 83rd precinct in Bushwick. You know, there’s nothing that they could do other than not exist. Right? But it took us a while to get there. I would say, you know, because we were trying to figure out our way. How do we challenge this system?

We quickly saw it’s not an individual cop, that’s the problem. It’s the whole thing, right? But [00:35:00] we focused on our local precinct, but really this is one precinct of a whole apparatus, right? So I would say our biggest success is kind of becoming abolitionists, I guess, right, in the process.

And switching gears completely to thinking inspired by what was happening in other places around the world to think about what would it be like to do organizing that is building the alternative to the police here in our local neighborhood, right? And so I will tie this with the next question about challenges. It is full of challenges how we did it, but we were able to envision what we called Sistas Liberated Ground, and it was like a physical territory.

We’re in this physical territory that’s in this neighborhood. We do not call the police, right? We will not call the police. We even had a pledge and people would say it out loud together, that we would say, “we will not call the police. Instead, we are gonna do this, this, [00:36:00] and this.” So. It was mind blowing for us to even do that, you know, to push ourselves to do that.

I would say some of the challenges were our peers at the time. We were also part of the Coalition against Police Brutality, New York City-wide. Some of them looked at us and said, this isn’t organizing anymore. You know, the organizing is, where’s the target? The demands, blah, blah, this? You’re building some alternative thing outside? That’s not organizing, you know? Saying that what we were doing is some kind of collective self-help.

We had some time there where we were feeling alone, you know, and not clear about what we were doing. Center for Third World Organizing, which we were aligned with, and we hosted their interns and had gone to their trainings – they also told us what you’re doing is not organizing, you know?

So we were a little bit floating there for a while, but still sticking to our vision. This is something that [00:37:00] feels to us as worthwhile practice. And that’s when we kind of got connected with what you’re talking about, kai, you know. Other groups that were doing some of this work that’s thinking of what I remember learning the word prefigurative politics, where we can prefigure today and now the world that we want and start to practice it in small ways.

And we realized we’d been doing that the whole time, you know? Even before we did our campaign work, the way we ran the organization was horizontal. We had a flat pay salary. We did, you know, when people had caretaking needs for babies or elders, we figured out the times for them to do it. It was all built in like, and it was written down as part of our, you know, HR, whatever, you know.

And so we were doing that. Even though we didn’t have the language to say we were doing it.

kai: We were always experimenting, always pushing, always challenging, and being challenged. And I think the success is that freedom to do [00:38:00] that. In addition to all the things that are going on around us not to feel the pressure of the choke hold, to the point that we let go of our values, our vision, our analysis, and our intentions, right?

And so I do think a success was to be able to stay and pivot and expanding as we pivoted. And I think the proof is in the pudding, right? Like where we are now is a demonstration that all of our work, collectively, has sprouted a movement where folks don’t even know we exist. The idea of building an abolitionist world or /and society as normal. And if that means that it’s anti-capitalist, if that means that you can’t have racial and gendered capitalism and have abolition, right, we all know that, right? That’s like, okay, that’s [00:39:00] basic.

If we have folks who are even today making those arguments, then I think that experimentation has been successful. And, and similarly, it’s challenging because we’ve lost a lot of people in terms of our health and our wellness. Organizing and activism is not, as we practice, is oftentimes not sustainable.

I think that’s gotten better, and I think we can draw on some of the new models of organizing to look at sustainability of ourselves and our planet, right? At that time, it was a challenge for us to take care of ourselves and take care of each other while we were fighting. Our practices were very, I think, uh, unhealthy.

Like, oh my God, I was such a smoker, you know, and I smoked long brown cigarettes, lots. And I think about two years I lived [00:40:00] off of, what were those strawberry candies like? Like, and coffee, right? Because all I did was go to meetings and I was pushing my body to a point that I can’t do that now at 63, right? I have to like have a different way of being in the work. Yeah. So that was a challenge. The sustainability.

Ejeris: Another piece about the challenges, I left the Audre Lorde Project in 2010, but by 2011, 2012, most of the safe spaces had been gentrified out because many of those most left, most POC, most friendly to the politics institutions, were also the most vulnerable to gentrification.

And so a lot of what the Safe Outside the System collective has been thinking about since that time has been navigating gentrification and how it impacts kind of place based safety. I think the other challenge, we navigated this intersection of – [00:41:00] Audrey Lorde project’s a nonprofit, right? So there’s nonprofit laws.

You know, we were trying to operate as a collective and a nonprofit, which, you know, if I had understood more the inherent contradiction when we started it, but I didn’t. I was like, this sounds cool, you know? And at that point in my politicization and eagerness, we had some real challenges that… we’d done so much work on how people create safety, but we had multiple instances of not necessarily like severe harm, but harm, right?

And there were organizational policies connected to nonprofit law that are a bit different than how we wanted to navigate it. And so that also kind of challenged the structure, like who really does get to make decisions. It was just this whole disheartening, really challenging piece where I think it’s a challenge for all of us, like the balance between the building of your internal community and collective and their work. [00:42:00] The work you do on protocols and agreements and how you treat each other, and the work that you also do on your organizing, you know, and how to split that time. Because I think the other challenge that like kai really spoke to is that I, I think some of the reasons we don’t see each other as much as that maybe we all are taking better care of ourselves and so we’re doing less, right?

Like, ’cause I was going 12 hours a day. There would be work, and then there’d be like dinner and then there’d be this and this event and things. And so it was all the time. And I was at an age and point in my life where that was fuel, right? I was living off of the adrenaline of being around inspiring revolutionaries all day long.

And so I think that, as nonprofits are more sustainable these days. There are whole funds dedicated to abolition. There are all these things that exist now that didn’t before, which both have [00:43:00] opportunities and huge challenges. But what it does give people the opportunity to do is to be healthier in the work, which I hope creates bigger movements, more longevity, more joy for people, less burnout.

‘Cause I think that sometimes there were points in my decision making or support that were not as expansive around us creating like all the protocols we needed internally, that were really based about exhaustion, you know? We absolutely did the best that we could, and there were some gaps that hurt us later on.

Deana: For sure. Folks were going nonstop for liberation at the expense of their wellbeing.

Now you kind of talked about this, and I would love if you wanted to expand on it. So at the time you were doing this work, there was clearly cross pollination, community collaboration. What were you all learning or observing from the work of other folks, and how did those [00:44:00] observations inform your work?

Paula: We learned from the MST in Brazil, we learned from the Zapatistas and others, where there were no cops. So what would they do? You know, when shit went down. And I think we had a few of those experiences where we actually put it into practice and felt our collective power, you know.

We felt like, yeah, this is organizing. This is organizing. It’s building collective people power and changing, you know, how people think, but outside of asking or forcing or pushing the state to do it for us.

For us, because we were basically like an afterschool program, you know? And from the outside, that’s what the world would see, right? This is where young women would come after school on weekends, summer camp, you know, to be with us, to do this holistic political education, you know?

And I think what expanded my mind was seeing how others were doing work that was kind of going more to the [00:45:00] root. We were responding to the violence, right. And trying to figure out how to do that in our collective people power way. But some of the work that you were doing, kai, some of the work that you were a part of, Ejeris and ALP, I think there was some work that was more about intentional, just community building as the first building block before you can do this, right?

Before you can do community accountability, you have to have community. You have to have a a community, and I think we kind of had that ready made in our afterschool program way of everybody goes to this school, this school in the neighborhood. But what we saw others doing was kind of doing the work that would come years before, you know. Tthat is building these intentional relationships of love, care, accountability through projects that weren’t specifically about cops or violence, right? That later give you a much [00:46:00] richer soil to do this work, and I think that is something that I learned watching others.

kai: One of the things I wanna think about is that kind of political theoretical continuum that we operated within to even get to the point where we were able to be as bold as we were. So I think that we don’t often look at the political theory that undergirds this kind of present day abolitionist movement. I think it comes out of a third world feminist analysis and praxis, right? Like a lot of what we draw from in terms of decision making, democratic participation, participatory democracy, consensus, you know, looking at the mundane and the everydayness of our experience and our work, looking at the whole person.

I know that to come [00:47:00] out of third world feminism, right, as a school of thought, and so I don’t think we often give that, really dynamic school of thought, the attention that we should, when we are thinking about how our, our left movement has evolved over the generations, right? And so I think this is our time, right? And so like the ways that we are intersectional, the ways that we are privileging the, the whole body, the personal is political in our work, right? It comes from that school of thought.

And I think one of the things that was really important for us in New York, and I think that also was the case in the Bay. It was also the case in Chicago. It was also the case in Detroit, Atlanta, New Orleans. I saw a lot of cross regional thinking or shared ideas, and one of the things that I think we were all open to was [00:48:00] experimentation.

And so to think about our work, one, as we are participating in making history, and two, we are experimenting. We don’t have all the answers, we’re engaged in this research and application process, right? Allowed us to keep working when we got patted on our heads and told that we were cute.

Deana: Yeah, I totally agree. This work is about experimenting and learning through practice, and since we have new folks coming up in this work who can learn from your brilliance, what else do you want them to know?

Paula: I would have a lot to say for younger folks. I think some of the core things I learned that were formative to me was the difference between organizing and activism back then, you know? Where it’s like, even if it’s a small crew ’cause in the beginning there was a small group of us at Sister II Sister. But the work was intentionally building [00:49:00] a base of members who all shared ownership in that project, right? And who had decision making power and, and we had a membership and all of that, even if we started with a few of us. And that very, uh, slow and intentional work of building collective power and building an organization, even though it wasn’t a conventional organization, it was an organization with clear kind of structure and power to everyone involved, doing that work intentionally in a horizontal way.

I think there’s so much now that’s going on where organizing and activism words are used interchangeably as though it’s all the same thing. And anybody who has like deep, sharp analysis on social media is doing organizing where it’s like, hmm, that’s not organizing. It’s important work, right?

But organizing is actually slower. Uh, it’s not as sexy often, often it’s gonna be not so visible for a long time. That’s the work that we need to [00:50:00] be doing more and more of. And I think everybody wants to be a public intellectual now, it feels like, you know. Everybody’s got like ba, you know, ba, ba and are so brilliant too. But that much more intentional work of whoever I am, there are others who are more directly impacted by this and have less access to all the resources and information that I have, and my role is to work with others to kind of grow that.

I think that’s essential. And that we need more of that. We have all this work now called abolitionist organizing that all of it’s beautiful, but a lot of it’s not actually organizing, you know, it’s kind of activism around it. And I think it doesn’t give us the, the legs, the rooting that we need. And so I guess along those lines, thinking about how the nonprofit industrial complex is so challenging. And I’ve been in and out of it for the last 30 years now, you know, thinking about are there ways that we can do this practice that’s, the organizing, [00:51:00] the slow steady burn of deep relationship building over time of growing, you know? Growing organizations, collectives, and then networking them all. Are there other ways to do that outside of the nonprofit industrial complex? You know?

And I think that’s been one of the things I’ve been struggling with the most because I have two kids, I gotta make a living, and I barely do half the time. You know that whole thing. For a lot of folks, setting up a nonprofit, starting to get grants, doing that is really the only way it feels like, right? To be able to do organizing.

So for me, it’s like … Some of us need to do that, and some of that nonprofit funded organizing work is very powerful right now. And I’m not saying to stop it, but are there other ways too? Can we be experimenting with other ways of doing that work? I’m a midwife now, and in order to search for a way out, I became a, a health worker, you know, a birth worker first through my own traumatic pregnancy experience, you [00:52:00] know, that kicked me into that path. And a doula first, then a midwife. And that practice, which is building very deep intentional relationships with families during the childbearing year. To me now, I’m like, whoa, this is like an organizer’s wet dream right here. You know what I mean? Like we get to meet and bond so deeply with all these beautiful people who then after come out on the other side and like, yo, I wanna be down with whatever y’all are doing. I wanna be down with this.

I see myself as a hybrid practitioner. I’m an organizer, but I work as a midwife, you know, I don’t work as an organizer anymore.Amd I think there’s lots of places in community and society that they’re hybrid practitioner potential that we’re not really working enough on. So I think about like school librarians, public school librarians, yo, they are amazing, a lot of them, and they are natural organizers and could be right? Public school teachers as well. Medical assistants in clinics and stuff who really do [00:53:00] the face-time with people and get paid shit, but actually know everybody. Those people are to me, naturally poised to do organizing, you know?

And so I’ve been thinking a lot about that. I feel like there’s something in between, right. In between those folks organizing in the workplace and then those who are doing more conventional community organizing or something in between. And that’s like these hybrid practitioners. And I’m using myself as like an experiment on that, and it’s not always going that well, but I think it’s possible.

Ejeris: I’m really just thinking about the point that you made earlier. Around how this work is connected to kind of third world liberation movements and, and feminism.

And I think that abolition has gotten so popular that the kind of ideological history is being separated and parsed out in a way that people are like identifying as abolitionists, like as an identity, [00:54:00] without being able to do some of the politics and study. So I was just gonna say to, to study at the feet of kai, I think that many people are talking about the ideological underdevelopment of our current state of the left that is connected to the way that the state took out so many of our brilliant revolutionaries, right?

And how people have created tactical projects without their kind of histories. I think that study and understanding that you’re in a lineage is really important. And I think connecting to that lineage and connecting to people in that lineage is really important.

if you’re an abolitionist, you should know Critical Resistance, right? You should be connected to Critical Resistance. You should know if you do transformative justice, you should know Creative Interventions. You know? So I think to be in the future and in the history that I, that I think of is really important,

kai: that history piece, right? To understand that you are in a [00:55:00] continuum of struggle, of joy, of changing the world. You know, I think it’s important to name drop in no names, but I think, you know, what is this name standing on? Like what is the analysis? What are the objectives, you know?

And so I think one of the things I’m curious about is if abolitionists today, or people who are interested in transforming the world, what is the ideological drive? Right? What’s your ideology? You know what I mean? Like I’m a Black liberationist, right? So I come from an ideology of I want to see Black liberation, right? I want to help promote and produce and keep Black liberation going until… until. That’s an ideological foundation, and I think the state tells [00:56:00] us that we should be anti-ideology.

I think we should be anti-fundamentalist, but I do think we need ideology because we have to have some objective of why we’re doing this work. If you have an ideology, it helps direct, guide how, what decisions you make and how you see change happening, right? And so I do think third world feminism is a ideological school of thought that is not isolated and by itself, but draws on many different ideological schools of thought.

And that work is an ongoing process. You change, you grow, you reject stuff you once held near, and you add stuff that you didn’t think was possible. It’s a organic process. Abolition is organic. It doesn’t begin and end. You don’t win abolition. It is not a prize, right? So like I, I [00:57:00] want us to think about ourselves as being in history and working with history to be able to leave something in the archives for the next generations.

Deana: Thanks to the amazing organizers that live and work in New York City who are making this world a better place for all of us every single day. As always, I encourage you to take the lessons you learned today and keep practicing.

Have you facilitated a process using community accountability tools or strategies? We wanna hear your stories. Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative wanna share new stories from people who are taking action to end interpersonal violence without the use of police or carceral systems? Find the link in our show notes to learn more.

Stories for Power is presented by Creative Interventions and Just Practice Collaborative. Executive produced by Mimi Kim, Shira [00:58:00] Hassan, and Rachel Caidor. Produced by Emergence Media. Audio editing and mixing by Joe Namy and iLL Weaver. Music composed by Scale Hands and L05 of Complex Movements in collaboration with Ahya Simone.

Stay tuned for more episodes of the Stories For Power Podcast. Check out our show notes and go to StoriesforPower.org to learn more.